Modernizing America’s bomber fleet isn’t so much about exchanging old aircraft for new ones. It’s a deliberate process that combines strategy, technology, and strategic planning to ensure the U.S. is able to deliver today’s requirements while keeping pace with tomorrow’s danger. The Air Force’s transition from the battle-proven B-1B Lancer to the all-new B-21 Raider illustrates precisely how modernization is more than merely acquiring new equipment—it’s about creating a stronger, more resilient force.

The B-1B Lancer, nicknamed by crews as the “Bone,” originally entered service in 1985. Designed for high-speed, long-range strike operations, it ultimately found itself performing much more than it was originally intended. During the past 20 years, it was utilised extensively for close air support and persistent combat missions—missions that placed a heavy burden on its composition and systems.

By 2019, fewer than half the fleet could fly, and it cost tens of millions to get each back in top form. The Air Force faced a difficult choice: continue to pour money into tired jets or begin shifting towards a leaner, more efficient bomber force.

In 2021, the choice crystallized. Seventeen of the oldest and most worn-out B-1Bs were retired, reducing the fleet from 62 to 45. This wasn’t about losing firepower—it was about focusing time, manpower, and resources on the bombers in the best condition. Most of the retired planes were sent to storage at the 309th Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Group in Arizona, with four preserved in case they were ever needed again.

The others were repurposed: one was made into a test site for structural repair, one for ground testing, another as a support for a mapping project, and one was placed in the Global Power Museum. Air Force officials stated that the effort freed up crews and maintainers to focus more on the remaining aircraft and maintain them better.

That foresight paid off when disaster happened in 2022. A Dyess Air Force Base B-1B was lost to an engine fire, which could have dropped the fleet below its required numbers. The Air Force went back to the “boneyard” and brought out a bomber in good condition, nicknamed “Lancelot,” which had been retired the previous year.

Squadrons from several bases collaborated to get it in the air again, in a test of bringing back to life an aircraft that had been stored in the desert. Eventually, Lancelot saw active duty again—a unique instance of a mothballed bomber successfully returning to the air.

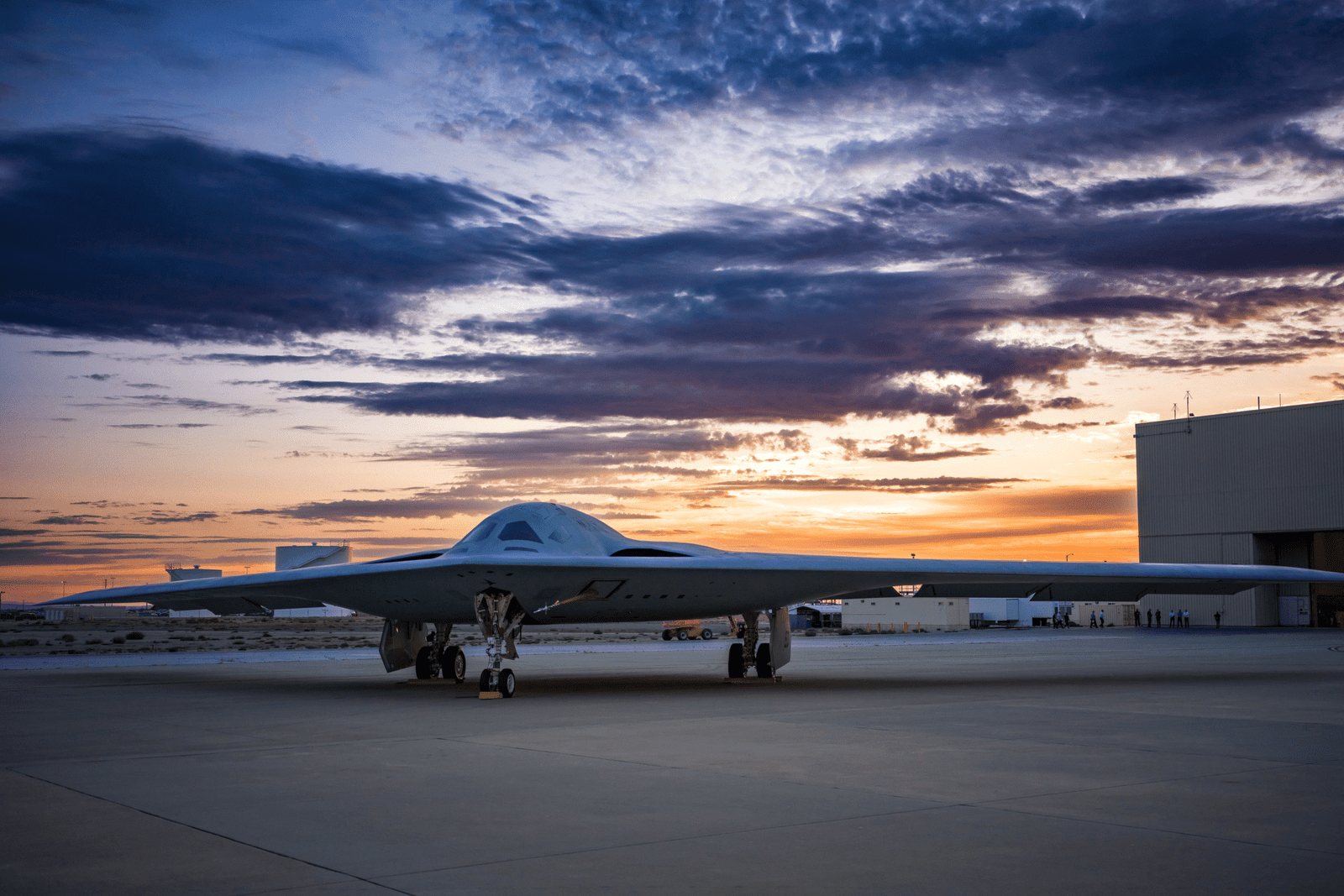

The bomber force’s future now depends upon the B-21 Raider, the first new US strategic bomber in over three decades. Scheduled to take over from the B-1B and stealthy B-2 Spirit, the B-21 is designed for the most demanding missions in hostile environments. It can be armed with both nuclear and conventional payloads, features advanced stealth technology, and has an open architecture that allows for simple upgrades. It can also fly manned or unmanned, providing commanders with greater flexibility in how it’s deployed.

Since the beginning, the B-21 program has emphasized cost control and accelerating production. Even the test planes are constructed to operational levels, so lessons learned apply directly to the jets that will go into service. Ellsworth Air Force Base in South Dakota will be the initial home for the Raider, followed by Whiteman and Dyess. The Air Force intends to deploy at least 100 of them, which will cost around $692 million each in 2022 dollars.

The bomber force is transitioning from three planes—the B-1B, B-2, and B-52H—to a more streamlined two-bomber force: the B-21 Raider and the upgraded B-52H. This strategy maintains the long-range strike capability robustly while making the force more maintainable and prepared for change.

Modernization here isn’t merely about producing the next bomber—it’s about making sure America can project power, reassure partners, and act fast in response to future threats. The B-21 isn’t merely replacing the B-2—it’s opening the door for the next chapter of American airpower.