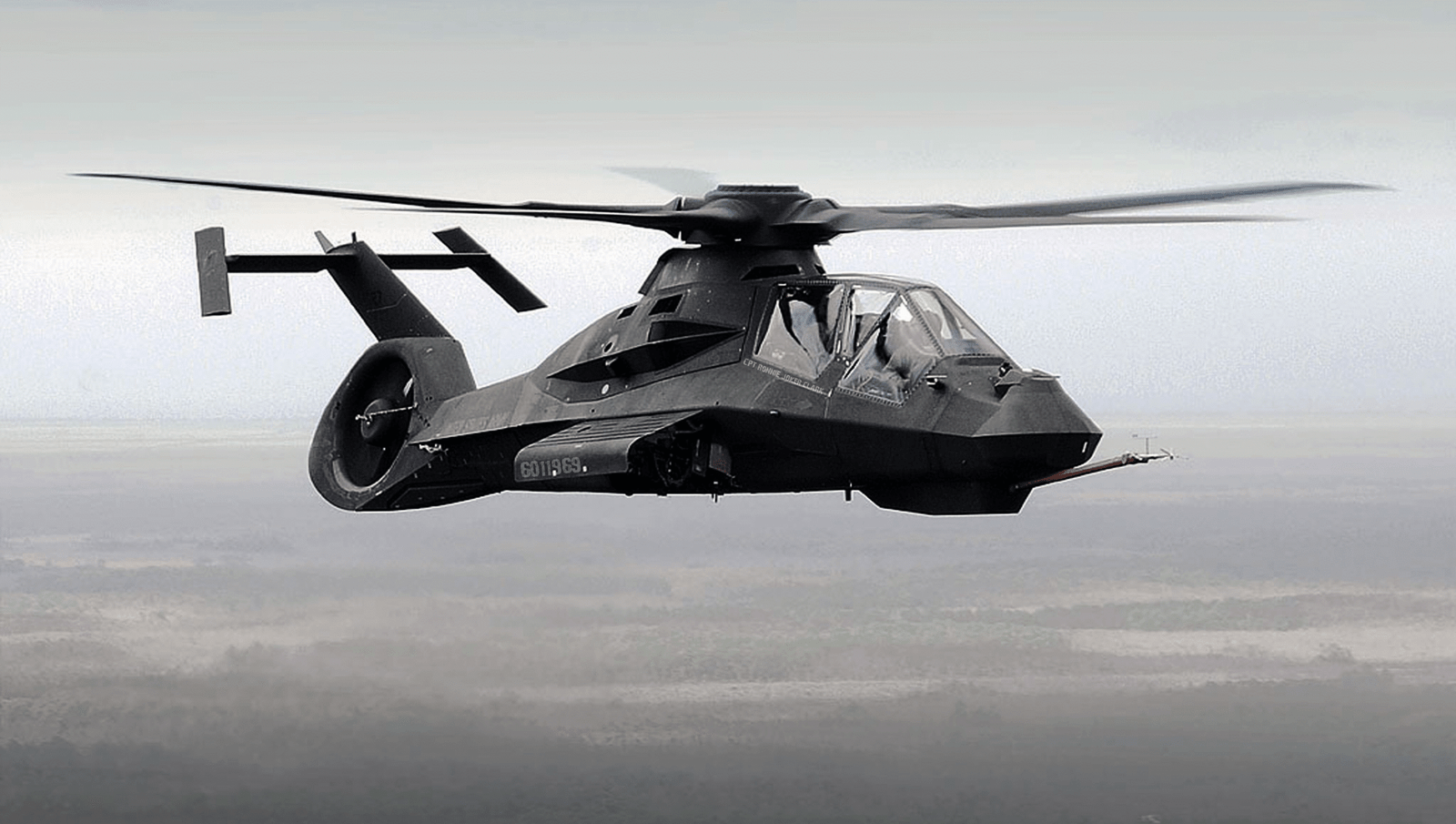

The Boeing-Sikorsky RAH-66 Comanche is still one of the most daring—and most educational—episodes in the history of U.S. military aviation. As the Army’s definitive stealth scout and light attack helicopter, the Comanche was to wed leading-edge technology, unparalleled maneuverability, and virtual invisibility on the battlefield. Its path from great hopes to sudden cancellation is a textbook example of the way military innovation can conflict with changing strategic conditions.

The Comanche traces its origin to the early 1980s, when the Army’s Light Helicopter Experimental (LHX) project aimed to replace an aged fleet of utility and scout helicopters like the UH-1 Huey, AH-1 Cobra, OH-6 Cayuse, and OH-58 Kiowa. The mission was ambitious: design a next-generation helicopter that would be both a stealthy reconnaissance platform and a quick, light attack aircraft. In 1991, Boeing and Sikorsky were awarded the contract, and the RAH-66 Comanche was born. The Army had dreamed then of producing more than 1,200 of them, each capable of sneaking into enemy land without notice.

Stealth characterized the Comanche’s very essence. Its fuselage was carved with faceted angles to disperse radar waves, then covered with radar-absorbing materials. A specific infrared-suppressant paint decreased its heat signature. A five-bladed composite main rotor and enclosed Fenestron tail rotor significantly reduced noise levels while reducing radar returns. The exhaust was thoughtfully channeled through the tail boom, cooling engine heat before it could give away the position of the helicopter. Comanche radar visibility was determined to be 100 times smaller than comparable helicopters, infrared emissions 15 times less, and noise six times less. Even its canopy glare and paint reflectivity were reduced to keep it out of sight.

Its interior was a spectacle of cutting-edge avionics. Mechanical linkages were replaced by fly-by-wire controls, providing pilots with precise handling. Helmet displays projected sensor data right into the pilot’s line of sight. Navigation systems integrate GPS with terrain-following radar for low-altitude maneuvering in harsh terrain. The battlefield management system enabled crews to observe, locate, and engage threats in real time. Sensors provided such advanced forward-looking infrared, night vision, and millimeter-wave radar, permitting all-weather, day/night-temperature target detection. The cockpit was even pressurized and safe from nuclear, biological, and chemical threats, enabling operation in the most hazardous environments.

Its weapon systems were just as sophisticated. Comanche was equipped with a stealthy retractable 20mm XM301 three-barrel rotary cannon in the nose, which could swivel through a large arc without compromising stealth when retracted. Internal bays covered up to six AGM-114 Hellfires or twelve AIM-92 Stinger missiles, leaving its profile clean and radar-refractive-free. Stub wings could be added to accommodate heavy firepower—up to eight Hellfires or sixteen Stingers—but this would compromise stealth. The modular configuration allowed the helicopter to switch rapidly between close support and armed reconnaissance missions.

Though promising in its very great potential, the Comanche was beset with problems. Integrating so many advanced systems into a single airframe was more difficult and expensive than anticipated. Technical problems and delays exacerbated costs, and year by year, the production numbers envisioned kept reducing. By 2004, after some $7 billion had been spent and only two prototypes had been built, the estimated completion price had risen to $14 billion, and the program became harder and harder to defend.

Meanwhile, the world itself had changed. The collapse of the Cold War eliminated the requirement for stealth helicopters in high-end warfare. New operational requirements from counterinsurgency missions in Iraq and Afghanistan pushed the Army’s priorities toward more near-term answers.

The helicopters it already had, like the Kiowa Warrior and Apache, could be upgraded quickly and cheaply. Meanwhile, unmanned aerial vehicles were quickly demonstrating their value, providing persistent surveillance and strike capacity without putting pilots at risk. In most situations, armed drones could perform the Comanche’s mission for much less money.

Confronted with increasing expenses, shifting priorities, and the expanding popularity of UAVs, the Army decided to terminate the program. The money was instead spent on improving the helicopter fleet and pushing forward on drone development. Although disappointing for its supporters, the move was part of a larger trend toward pragmatism and flexibility in procurement.

The Comanches’ history didn’t end there. Several of its innovations—stealth shaping, sophisticated composites, digital flight controls, and sensor integration—found their way into other helicopters and unmanned platforms. Its two prototypes, preserved at the U.S. Army Aviation Museum in Alabama, serve as a reminder of both the extent and the limitations of ambitious defense ventures.

Ultimately, the RAH-66 Comanche was more than a helicopter—it was a glimpse of what could be accomplished when ambition, design, and technology came together. Although it never made it to service, it had a lasting impact on the things it taught and the technologies it begat.