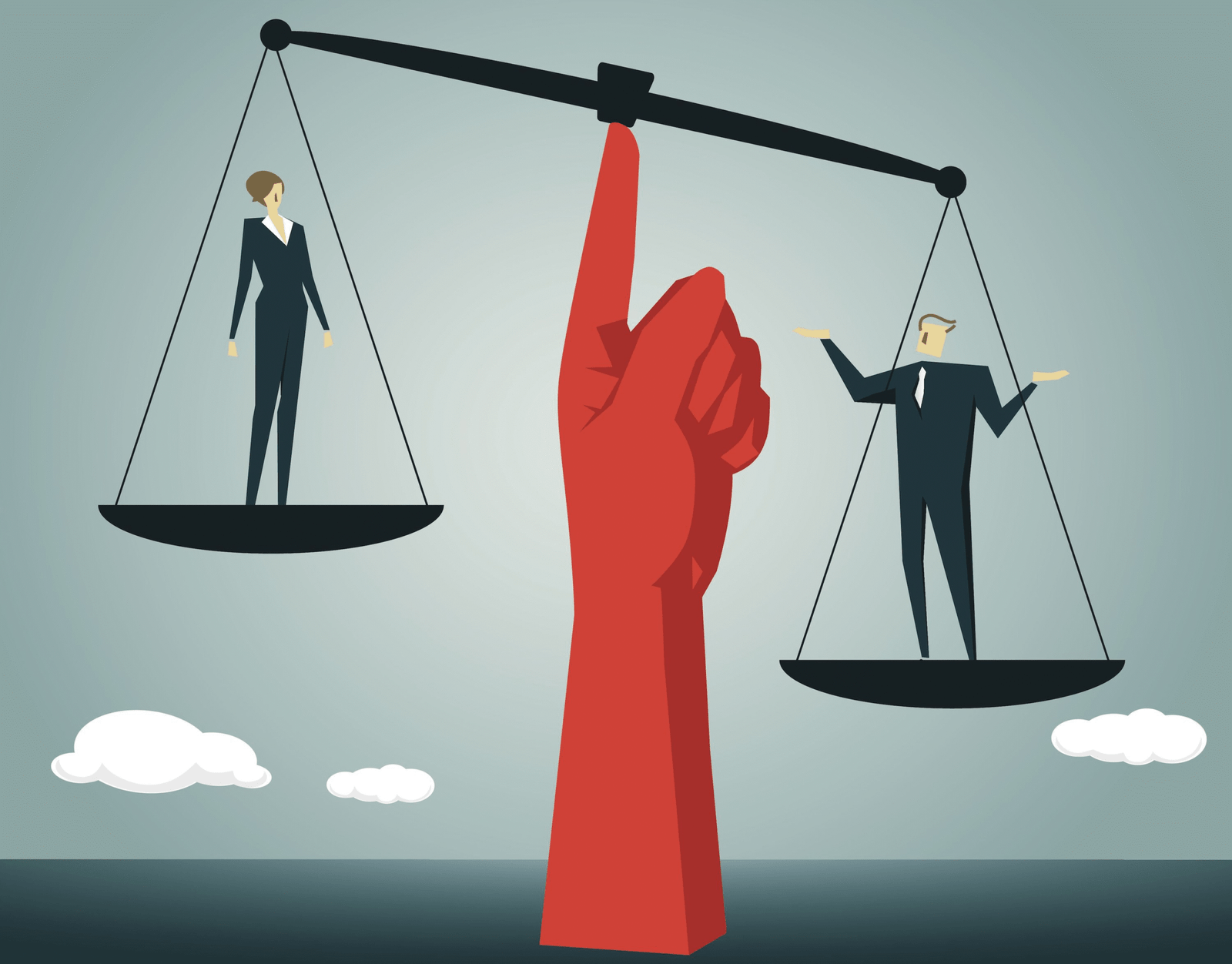

For generations, many have accepted patriarchy—the rule of men over women—as a natural, almost inevitable part of human society. But peel back the layers of history, and you’ll find a much more complicated, and frankly, more hopeful story.

The Myth of Patriarchy as Human Nature

It’s tempting to look at the world as it is and assume it’s always been this way. For most of the 20th century, even scientists were caught up in this same trap. Consider that infamous “Monkey Hill” at London Zoo in the first half of the 1900s, where an imbalanced baboon enclosure—too many males, not enough females—became a violent, chaotic nightmare. From the outside, it appeared to be a window into our evolutionary history: sparring males, victimized females, and a natural hierarchy of male dominance.

But as science writer Angela Saini suggests, this was a skewed environment, not nature. Indeed, many of our closest primate cousins, such as bonobos, are matriarchal, with women in charge, despite being physically smaller than the men. Throughout the animal kingdom, and indeed within the human species, the notion that male dominance is “natural” simply doesn’t stand up.

What History and Archaeology Reveal

Go deeper in human history, and the tale gets still more intriguing. Archaeological remains such as Çatalhöyük in contemporary Turkey, around 9,000 years old, reveal few signs of gender hierarchy. Men and women consumed the same foods, performed similar tasks, and lived adjacent to one another with little distinction in status or opportunity. Even the celebrated Seated Woman of Çatalhöyük—a robust, matronly female positioned beside leopards—hints at a society that celebrated women as much as men.

And it isn’t ancient history. Anthropologists have documented at least 160 matrilineal societies that still exist today, in which property and family identity are passed through women, rather than men. Power is shared in these societies, and leadership may be a cooperative effort between men and women. Men assisting in raising the children of their sisters are typical among the Mosuo of China, while both queen mothers and male chiefs collaborate among the Asante of Ghana.

Then, if patriarchy is not embedded in our genes, where did it originate from?

The Rise of Patriarchal States

The actual watershed moment, say historians and archaeologists, was the emergence of the world’s first states in ancient Mesopotamia around 5,000 years ago. As human societies expanded and became more sophisticated, elites had to control resources—and humans. Administrative records from cities such as Uruk indicate a new fixation on classifying populations, keeping tabs on resources, and making certain everyone played their “proper” role.

This was when pressure on women to concentrate on bearing children intensified, particularly bearing sons who would be able to serve in wars or work for the state. Personal abilities and wishes counted less than finding one’s place within the state’s needs. Women were increasingly forced out of public life and leadership, housed at home, and more and more regarded as property, like children and slaves.

The change was backed up by customs such as patrilocal marriage, where women moved away from their own families to reside among their husbands’ relatives, leaving them more susceptible to abuse and exploitation. Marriage itself was transformed into a legal arrangement aimed at regulating women’s and property transferring down the male line.

The Psychological and Social Toll

Perhaps the most pernicious legacy of patriarchy is how it rendered its order “normal”—even natural. As Saini writes, the psychological harm was deep-seated, creating distrust and splits within families and communities. Gender stereotypes—femininity as nurturing, masculinity as violent—became self-fulfilling prophecies, confining everybody’s potential except for those at the top.

This system didn’t only disadvantage women. Men who didn’t fit the script—men who didn’t wish to fight, or who preferred nurturing positions—were ridiculed or pushed to the margins. The patriarchal state was created to benefit a narrow elite, not the many.

Challenging the Narrative: Women Who Refuse to Be Boxed In

In spite of hundreds of years of instruction on what they may and may not do, women have consistently managed to resist. From Marie Curie, who became the first Nobel laureate in two separate sciences, to Katherine Johnson, whose mathematical talents assisted in sending astronauts into space, women have broken down doors in areas long controlled by men.

Others, such as Malala Yousafzai, have put their lives on the line to advocate for girls’ education, while authors such as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie speak out against cultural expectations and help us better understand gender and identity. Despite economic struggle, disability, or bias, women such as Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Oprah Winfrey have demonstrated that determination and perseverance can alter not only their fortunes but the world at large.

Establishing boundaries—speaking “no” to what society wants and “yes” to what’s right—has been a key avenue for women taking back their power. By saying no to what others had tried to do for them, they’ve created doors for generations to come.

The Continuing Battle—and the Promise of Equality

Patriarchy might have crafted much of our past, but it’s not fate. As Saini puts it, “A society made by humans can also be remade by humans.” The continuous struggle for gender equality, from the right to work and study to the right to call one’s shots, is evidence that the tale isn’t yet complete.

Every time a woman challenges a stereotype, breaks into a new field, or simply lives on her terms, she chips away at the old order. And every time a man rejects the narrow roles assigned to him, he does the same. The path to equality is long and winding, but it’s one we’re all walking—together.