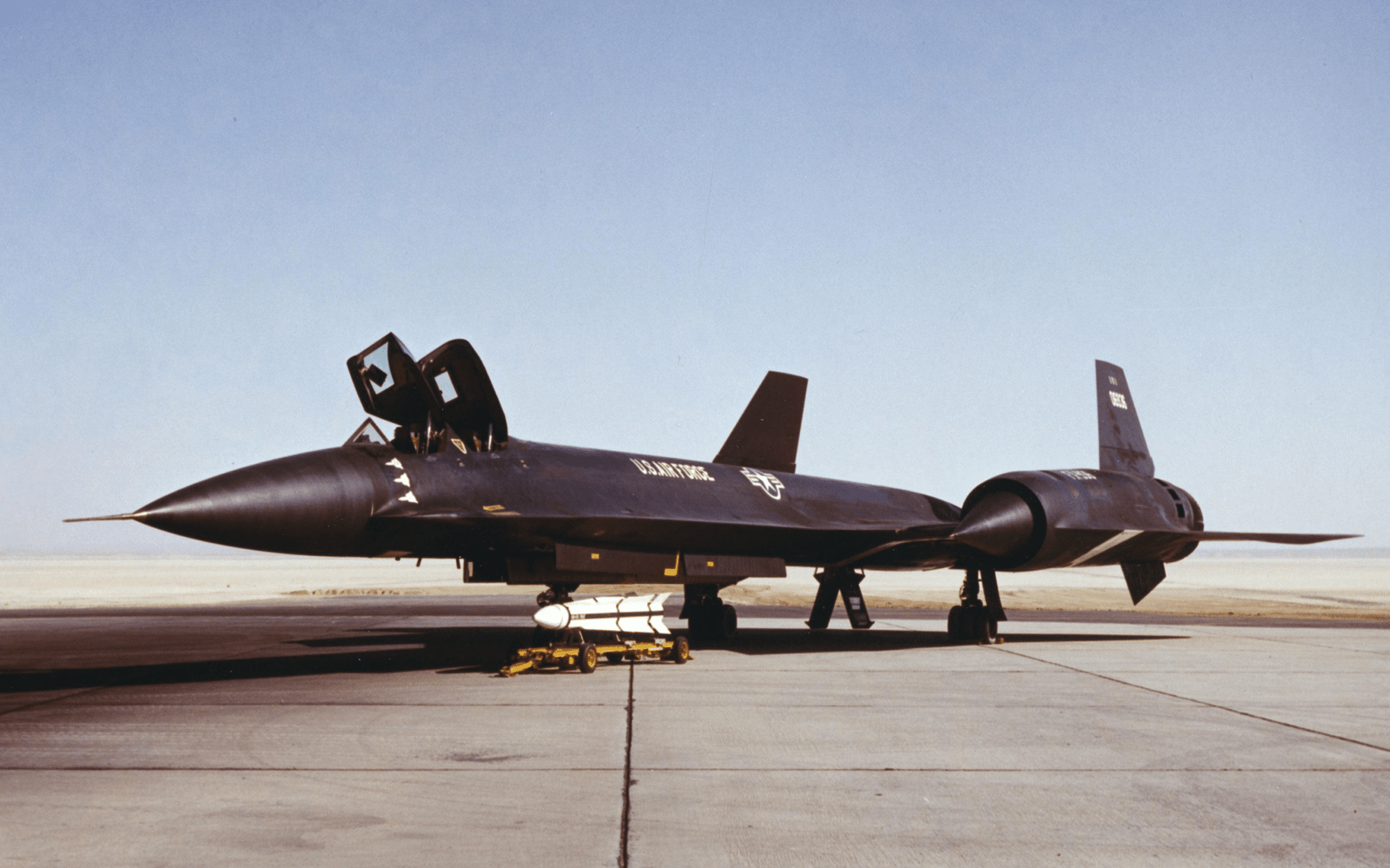

Few aircraft in history have pushed the boundaries of speed, height, and technology further than the YF-12A. Born of the same father as the legendary SR-71 Blackbird, this Cold War interceptor wed record-setting performance with technologies decades beyond their time. Its story is one of engineering brilliance, secrecy, and ambition, one that has had a lasting impact on military aviation and space exploration even up to today.

The YF-12A was never just a high-speed interceptor. Near the end of the program, the aircraft itself proved priceless as research vehicles to NASA and the Air Force. Flights during this period directly impacted the design of the Space Shuttle and were contributors to current developments in high-speed aerodynamics.

Beyond its experimental use, the YF-12A also proved to be a contributor to future military technology. Its missile and radar technology led to the development of the AIM-54 Phoenix missile and AWG-9 radar, subsequently installed in the F-14 Tomcat, providing it with a lasting technological legacy in multiple generations of aircraft.

The YF-12A was heavily classified from the outset. It was built during an anxious period of the Cold War, and its actual purpose was revealed to very few individuals in the government. When then revealed officially in 1964 under the cover title “A-11,” the disclosure otherwise well covered up the fact that there existed a yet more secret A-12 spy project operated by the CIA.

All aspects of the project were under tight wraps: the engineers were told not to speak about what they were doing, and the procurement of key materials was channeled through covert sources, so that the plane was under cover from potential enemies.

Technically, the YF-12A was impressive. Its Hughes AN/ASG-18 fire control radar, the first pulse Doppler radar ever installed on a U.S. aircraft, was capable of detecting bomber-sized targets over 100 miles away. With an infrared homing system, the YF-12A could home in and destroy low-flying targets—a capability few fighters of the era had.

Its weaponry was impressive too. With three AIM-47 Falcon missiles with a Mach 4 capability, the plane was lethal in tests, such as when it destroyed a drone bomber flying barely 500 feet above ground level after one was fired from 74,000 feet at Mach 3.2.

It was designing an aircraft that can maintain speeds of over Mach 3 that presented unique challenges. Titanium had to be able to resist the blistering heat produced at such speeds, but acquiring sufficient amounts of it in the United States was an enormous hindrance.

In a maneuver that seemed straight out of a Cold War spy novel, most of the metal was acquired through sophisticated, backdoor deals, smuggled into the program quietly to supply the critical material for an airplane capable of pursuing enemy bombers at unprecedented speeds.

At the core of the YF-12A legend, though, was its performance. It established world records in 1965 by cruising at a speed of 2,070 mph and climbing to altitudes above 80,000 feet. The speeds were unbelievable during those times.

The plane could cruise at Mach 3.2 at altitudes beyond which most interceptors or missiles could not reach. It was more than an interceptor; it was a guardian of the skies, a warplane that altered what could be done and had a lasting impact upon the history of flight.