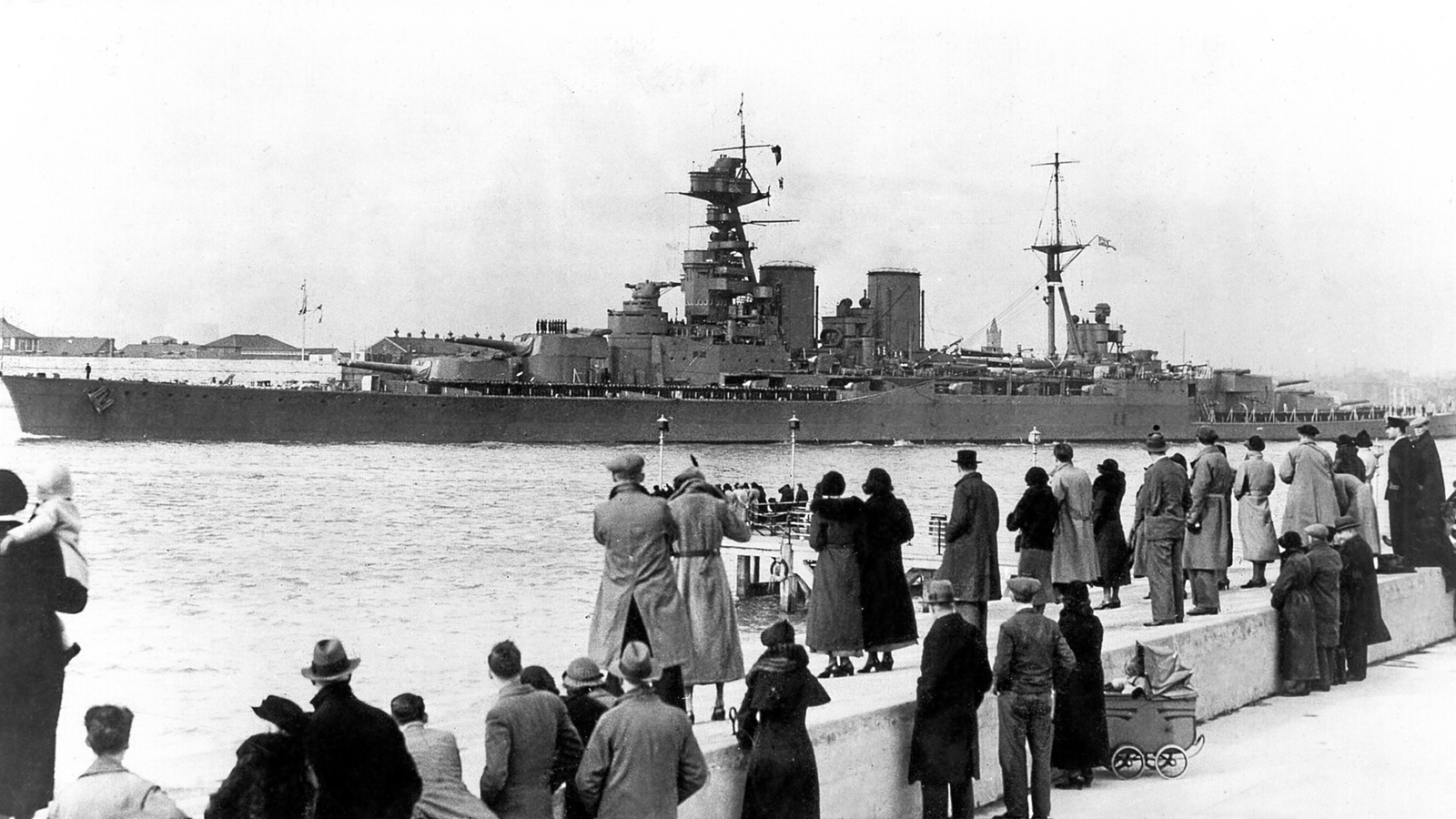

HMS Hood was not simply a warship but rather the pride of the Royal Navy, a strong symbol of British naval power for a period of over twenty years. When she sank in the Battle of the Denmark Strait on May 24, 1941, only three of her 1,418 crewmen were left alive. The nation was shocked by the loss. In a single blaze of fury, the Navy’s best-known vessel was lost, and for decades the explanation appeared straightforward: a fortuitous German shell from the Bismarck battleship hit Hood’s magazine and released a disastrous explosion.

Two World War investigations cemented this account into the record, reinforcing lessons learned at Jutland in 1916, when British battlecruisers had suffered similarly. It was, according to the official account, Bismarck’s fifth salvo that hit its target. Witnesses on the nearby HMS Prince of Wales reported a colossal column of flame erupting as Hood disintegrated. It was an image soon fossilized into memory.

But even then, there were some naval commentators who felt queasy. Sir Stanley Goodall, the Director of Naval Construction at the Admiralty, acknowledged that the “lucky hit” hypothesis was nothing more than the best educated guess, not a fact. He picked up on peculiar facts—such as the delay before the blast—that didn’t entirely add up to the equation.

In recent years, the controversy has been rekindled by researcher Martin Lawrence, a physicist and metallurgist who came to the tragedy with a new perspective. His controversial hypothesis is that Hood was not destroyed as directly by German gunnery as has been previously thought. Instead, he postulates the disaster as possibly being due to a mechanical malfunction: a fractured propeller shaft compromised by years of stress.

Lawrence raised the issue of Able Seaman Robert Tilburn’s testimony, one of the survivors of three, who remembered that after Bismarck’s second salvo, Hood started “shaking with a great vibration.” To Lawrence, violent shaking was less indicative of a shell hit and more in favor of something disastrous occurring within the ship’s power plant.

His logic is grimly sound. Hood’s inner shafts passed perilously close to her primary magazines, which contained more than 100 tons of cordite propellant. If such a shaft had broken, years of wear combined with battle stresses may have made it rip loose, smashing bulkheads and shooting white-hot shreds into the magazine compartments. That would have set a fire, which might have continued to spread until the magazines exploded. As opposed to the sudden annihilation presented in the official account, this chain reaction would have taken a minute or two—long enough for witnesses to observe the strange vibrations before the deadly blast.

But others are not convinced. They suggest that violent shaking might just as well be the result of near collisions or underwater explosions. They note that when propeller shafts do fail, they tend to snap and not lash wildly about, and that damage tends to cause flooding more than fire. They also highlight the fact that cordite is not easily detonated—it needs to be subjected to an awful lot of heat and pressure—so the shaft-failure hypothesis hardly seems likely.

What cannot be disputed is that by 194,1, Hood was not the ship of war she once was. Commissioned in the post-Frankfurt Peace War period, she had served hard for many years. Her major refit had been delayed by the advent of the Second World War, and she was consequently equipped with machinery that was now out of date and requiring continuous attention and repairs. Between 1939 and 1,941, she received several dockyard refits, and even the most senior admirals doubted that she could consistently make top speed for extended periods.

Eyewitness testimonies such as Tilburn’s are important but not necessarily trustworthy in the heat of combat. Officials during times of war might have preferred a more romantic account—a grand vessel lost in combat by the enemy—than the less sensational concept of a mechanical failure. Lawrence suggests that national pride could have influenced the way the account was presented.

Nevertheless, most naval engineers and historians still assume the official explanation is the most credible: that Bismarck gunners hit where it counted the most, and the resultant explosion was the horrific but immediate consequence. Other vessels, exa, HMS Prince of Wales, did experience severe shaft damage during the war, but there, at least, the impact was flooding, not instantaneous destruction.

So why does the debate continue more than eighty years later? Because the story of Hood isn’t just about one battle. It raises questions about how long great warships can be pushed before age and fatigue catch up with them. It also reminds us that history isn’t always as straightforward as the first reports make it seem. Whether Hood was sunk by a German shell or by some latent weakness in her own equipment, her loss is a chastening reminder of vulnerability—the terrible fate of a ship that had once seemed invincible.