The history of the Japanese battleship Yamato is not merely the history of the sinking of one gargantuan warship—it’s the history of a moment of change in naval history, when centuries of assumptions about sea power were turned on their head by the arrival of a new kind of warfare.

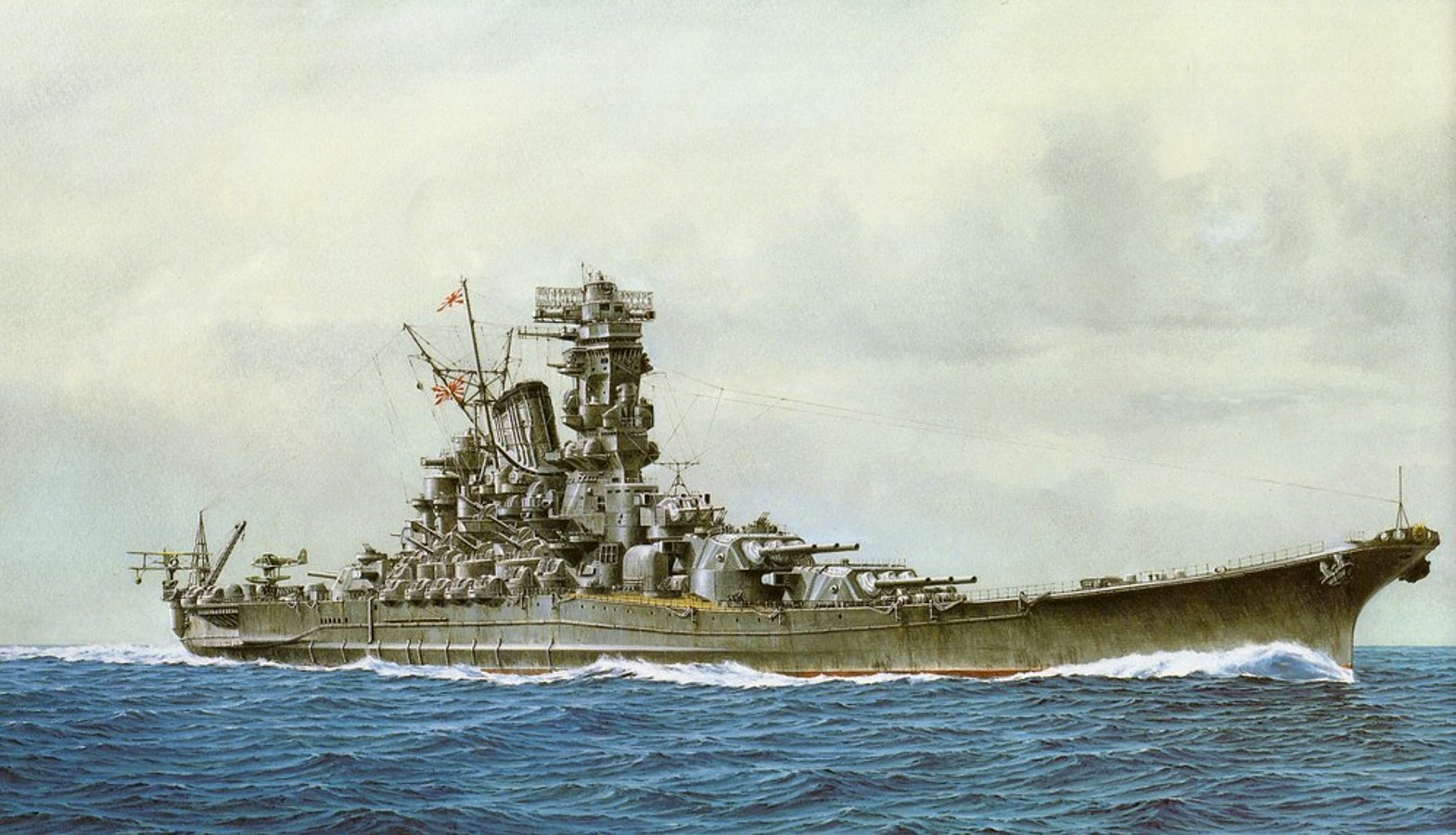

Secrecy shrouded Japan’s building of Yamato during the 1930s. The Imperial Japanese Navy wanted a ship strong enough to overpower any enemy, but mostly the U.S. Navy. With a loading displacement of nearly 70,000 tons and a length of 863 feet, Yamato was a floating fortress featuring nine enormous 18-inch guns—the biggest mounted on any battleship. Her armor plating was sufficient to absorb the thickest of shells, and her guns could reach out to targets beyond 25 miles. It was an elementary principle: if you cannot keep pace with the volume of the enemy, craft something so powerful that it can attack several ships at once.

But even before Yamato and her sister ship, Musashi, were finished, the face of naval warfare was evolving. Aircraft carriers were beginning to dominate the seas, able to attack well beyond the range of any battleship’s cannons. Nevertheless, Yamato was commissioned in December 1941 as a reminder of Japan’s maritime might. But during most of her life, she sat idle in port, held back by fuel reserves and the defensive strategies of an increasingly under-pressure navy.

Her pre-LAST wartime service was calm. Her biggest battle had been at Leyte Gulf in October 1944—the biggest ever sea battle. Yamato had used her main guns there, but the real battle had been won in the skies. American carrier aircraft pounded the Japanese fleet, sinking Musashi to the depths and destroying several others. The encounter was a hard-nosed wake-up call: air power now ruled the seas, and battleship encounters were history.

Japan was in a state of crisis by the spring of 1945. American forces had captured Iwo Jima, the Japanese cities were being reduced to rubble by bombing missions, and the Okinawa campaign was underway. Desperate, Japan launched Operation Ten-Go—a suicide mission aboard Yamato, light cruiser Yahagi, and eight destroyers headed for Okinawa.

The plan was gloomy: Yamato would drive herself aground and be a stationary gun battery against American invasion forces. She was equipped with hardly enough fuel to make the journey, with no possibility of return.

The decision was rash. Misunderstandings about the emperor’s intentions and a desire to uphold naval pride dispatched commanders to advance without proper planning. Many on Yamato allegedly felt that the mission was ill-conceived. On April 6, 1945, the task force left, carrying over 3,300 men—men who knew they were not going to come back.

The U.S. Navy was ready. On April 7th, American search planes located the Japanese fleet. Task Force 58 deployed over 300 carrier-borne planes to intercept. The attack was rapid and relentless. Dive bombers and torpedo planes came in waves, attacking from every direction. Yahagi was sunk early, some destroyers were lost, and Yamato took several torpedo and bomb strikes.

Flooding knocked out her power and steering, and she was dead in the water. The last wave of torpedo attacks caused her guns to blow up in a massive explosion. At 2:23 p.m., she had rolled onto her side and was sinking, with more than 3,000 crew members with her. 269 men were saved. American losses were few—only 10 aircraft and 12 men.

The sinking of Yamato wasn’t merely the destruction of a vessel but the final proof that the era of the battleship was over. Earlier battles like Midway had already hinted at this transition, but the death of Yamato made it indubitable. Aircraft carriers, not mighty guns-carrying warships, would now determine naval superiority.

For Japan, Yamato represents a lasting icon of national pride, sacrifice, and the tragedy of fighting a war with outdated ideas. For military historians, her fate is a stark reminder that the nature of tactics and technology shifts, and to refuse to abandon the old is to be condemned. Designed for a form of warfare that no longer existed, Yamato went into history as both the largest battleship ever built and one of the last of its kind.

Now, she rests a thousand feet beneath the ocean, a silent tribute to the courage of her sailors and the day that naval combat was changed forever.