There are airplanes in the history of flight that everyone knows—and then there are the stealthy, quiet game-changers. The Boeing YF-118G Bird of Prey falls clearly in the latter group. Designed and tested in total secrecy in the 1990s, this prototype aircraft wasn’t about speed or firepower—it was about redefining the rulebook on stealth.

Developed within limited budgets while stealth technology was still in its infancy, it demonstrated that revolutionary concepts could be experimented with, developed, and rendered feasible without the expense of a huge weapons program. Its legacy can be seen in almost every contemporary stealth fighter in the skies today.

The Bird of Prey came into being at a time of disappointment and resolve for McDonnell Douglas. Having lost out in key fighter competitions, such as the one that introduced the world to the F-22 Raptor, the company realized it would have to get stealth right if it was going to remain in the competition.

In 1992, its Phantom Works division went about doing just that in secret, building a technology demonstrator that would not only extend the limits of radar evasion but demonstrate that advanced aircraft could be rapidly produced and inexpensively.

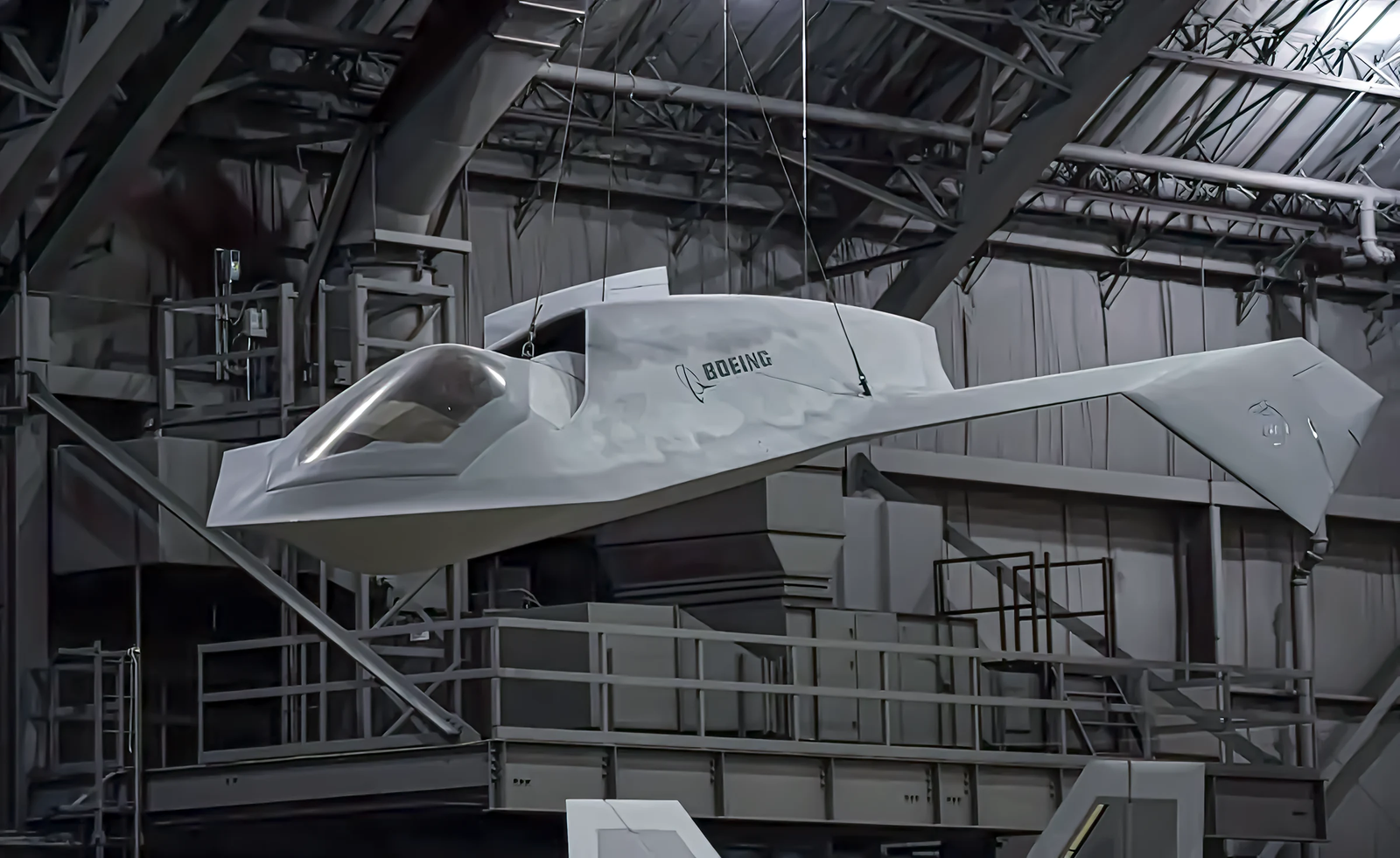

Its appearance was science fiction-esque—appropriate, considering its namesake was a Klingon warship from Star Trek. It featured a tailless, blended-wing-body design with angled wingtips and flat, unbroken surfaces to disperse radar waves. Stealth was carried to the limit by engineers with single-piece composite panels, shapeless control surfaces, and a precisely concealed engine intake to minimize radar and infrared signatures. The objective was straightforward: as nearly invisible as technologists could manage to sensors and even the naked eye.

As impressive as its appearance was, so was its price tag. The designers of the Bird of Prey made extensive use of spare parts to minimize the cost. The engine was taken from a business jet, the landing gear from a Beechcraft, and the ejection seat from a Harrier. Controls in the cockpit were a combination of materials cobbled together from other jets. This frugality kept the entire program costing only $67 million—a remarkable amount compared to all but the smallest of stealth programs at the time.

In terms of speed and altitude, the Bird of Prey was unpretentious, peaking at about 300 miles per hour and 20,000 feet, significantly less than most fighter jets. Performance wasn’t its intention, however. The flight crew emphasized flight stability without the help of computers, instead using aerodynamic stability rather than complicated fly-by-wire systems. Each flight was a matter of data collection and demonstrating the workability of new materials, forms, and assembly methods.

The first flight was conducted on September 11, 1996, in the desert skies above Groom Lake or Area 51. In the following years, the Bird of Prey flew nearly 40 times, with each flight further polishing its stealth profile and demonstrating that next-generation aircraft could be engineered in record time. The project remained classified until 2002, when the plane was unveiled and put on exhibit at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force. Even there, suspended from the ceiling, its cockpit is concealed, keeping a few secrets to itself.

The Bird of Prey’s real legacy is in what followed. Its advancements directly informed other programs, such as the Boeing X-45 Unmanned Combat Air Vehicle and the X-32 Joint Strike Fighter demonstrator. Insights from its formative and material use also informed operational stealth fighters such as the F-22 Raptor and F-35 Lightning II. Many of the stealth concepts demonstrated in the 1990s are still used in advanced programs today.

Whispers persist regarding features never officially announced—adaptive camouflage, test coatings, or other technology decades before its time. Whether or not they’re accurate, the plane’s strange silhouette and cryptic beginnings have guaranteed it a reputation as a favorite among airplane buffs.

Ultimately, the Bird of Prey’s tale is one of subtle but enduring impact. It never bore arms or saw combat, yet it indirectly influenced the future of air warfare. Crafted with creativity, tested in secrecy, and recalled for its innovative design, it is a testament that sometimes history’s greatest breakthroughs occur well away from the limelight.