The 1960s were crowded with a race for faster, higher-flying jets that made headlines and awed airshows. But beneath this pursuit of speed and altitude, a squat, subsonic strike aircraft came unobtrusively into U.S. service and became one of the most dependable combat machines of its day. The A-7 Corsair II was not supersonic or sleek but provided something much more valuable—dependability, durability, and accuracy. For more than 25 years, it was the mainstay of American strike aviation.

The A-7 saga began when the U.S. Navy recognized that its stalwart A-4 Skyhawk, good as it was, could no longer meet the growing demands of modern warfare. Something to take its place was in the works—a more gun-laden plane, one that would go farther and still be inexpensive and simple to service. In 1963, the Navy issued a call for a new aircraft with one unusual requirement: it had to be drawn up around an already current design in the interest of time and expense savings.

Vought Aircraft, already famous for the legendary WWII F4U Corsair, accepted the challenge. Engineer John Russell “Russ” Clark led the team in working on the F-8 Crusader. They reduced the length of the fuselage, eliminated the complicated variable-incidence wing, and substituted the afterburning engine with a more power-efficient turbofan. What it gave was a shorter-looking Crusader but with capabilities much greater than anyone expected.

What actually set the A-7 apart from other aircraft was its cutting-edge design. It was the first American aircraft to feature a heads-up display (HUD), which allowed pilots to keep important flight and targeting data in their field of vision without glancing downward. Its radar and avionics allowed it to strike with breathtaking precision—even in bad weather. Combined with its computerized bombing system, the Corsair II offered accuracy never before seen from an American strike plane.

The U.S. Air Force adopted its own variant, the A-7D, fueled by the powerful Allison TF41-A-1 engine—a Rolls-Royce Spey turbofan licensed production. With an extended wingspan for increased lift and stability, the aircraft gained impressive range and payload.

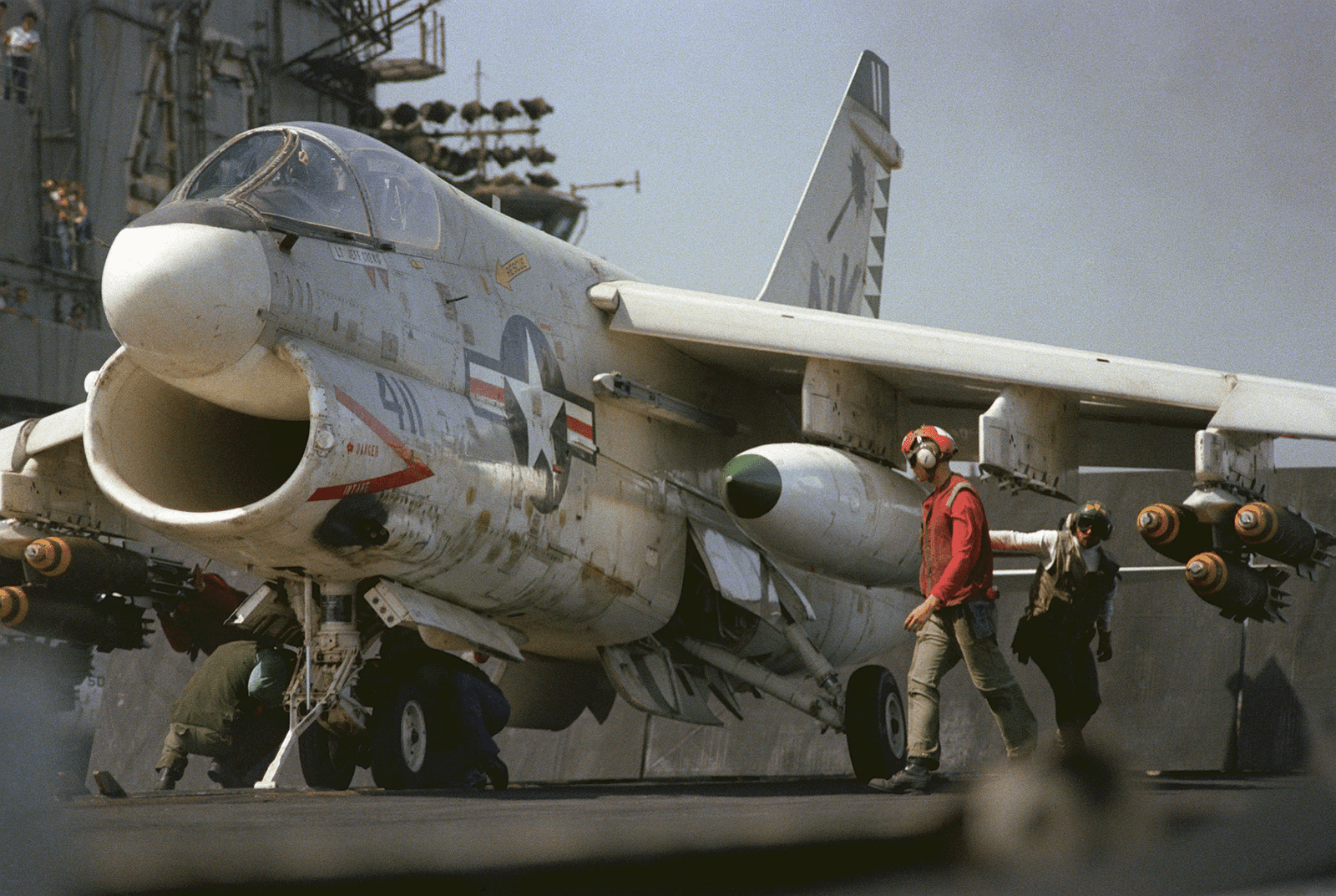

On paper, the numbers of the Corsair II were impressive. It could deliver over 15,000 pounds of missiles and bombs on eight pylons, and possessed a combat range of over 1,200 miles. Its payload varied from the old-fashioned iron bombs and cluster bombs to the more high-tech guided weapons such as the AGM-65 Maverick and Walleye. Although it lacked the flash of afterburners and Mach numbers, pilots grew to love the forgiving qualities of the A-7. It was rugged, sensitive, and easy to handle—qualities of greater value in the low-altitude strike operations in Vietnam than raw speed was ever likely to be.

Its longevity soon earned its respect. With armored cockpit, redundant systems, and heavy-duty construction, it coaxed crews back to safety through dangerous missions. The statistics bear it out: during the Vietnam conflict, Navy and Marine A-7s made more than 97,000 combat sorties at a loss of only 54 aircraft, while the Air Force’s A-7Ds made nearly 13,000 sorties at a loss of six aircraft.

The A-7 did not disappear with Vietnam. It continued to fly in almost every U.S. operation of the late 20th century, from Lebanon and Libya to Grenada, Panama, and finally the Gulf War. Its flexibility—capable of performing both close air support and interdiction missions—kept it useful long after more advanced aircraft were available.

Over the years, the Corsair II was progressively refined. The first A-7A was followed by more advanced versions like the A-7B and A-7C, featuring more powerful engines and enhanced avionics. The Air Force’s A-7D brought in the TF41 engine, advanced navigation gear, and the M61 Vulcan cannon. The Navy’s A-7E represented the pinnacle of the design, featuring state-of-the-art systems and capable of carrying the latest precision-guided bombs.

Its popularity was not limited to the U.S. Navy and Air Force. Allied nations like Thailand, Greece, and Portugal operated the Corsair II, keeping it in service well into the 21st century. Cost was also one of the A-7’s biggest strengths. With less than $1 million per airplane in the 1960s, it was a steal compared to such warbirds as the F-4 Phantom. It’s more efficient turbofan burned less fuel, and ground crews adored its simple layout, quick engine changes, and minimal maintenance.

In hindsight, the A-7 Corsair II demonstrated that glamour and speed aren’t always the greatest indicators of a fighter aircraft’s value. Its precision, toughness, and cost-effectiveness made it stand out in the annals of military flight. Despite its 1991 retirement from U.S. air fleets—and its last combat flights with Greece in 2014—the Corsair II continues to be honored by those who piloted and serviced it, maintained in the memory for not leading the pack across the sound barrier, but for getting the job done when it counted.