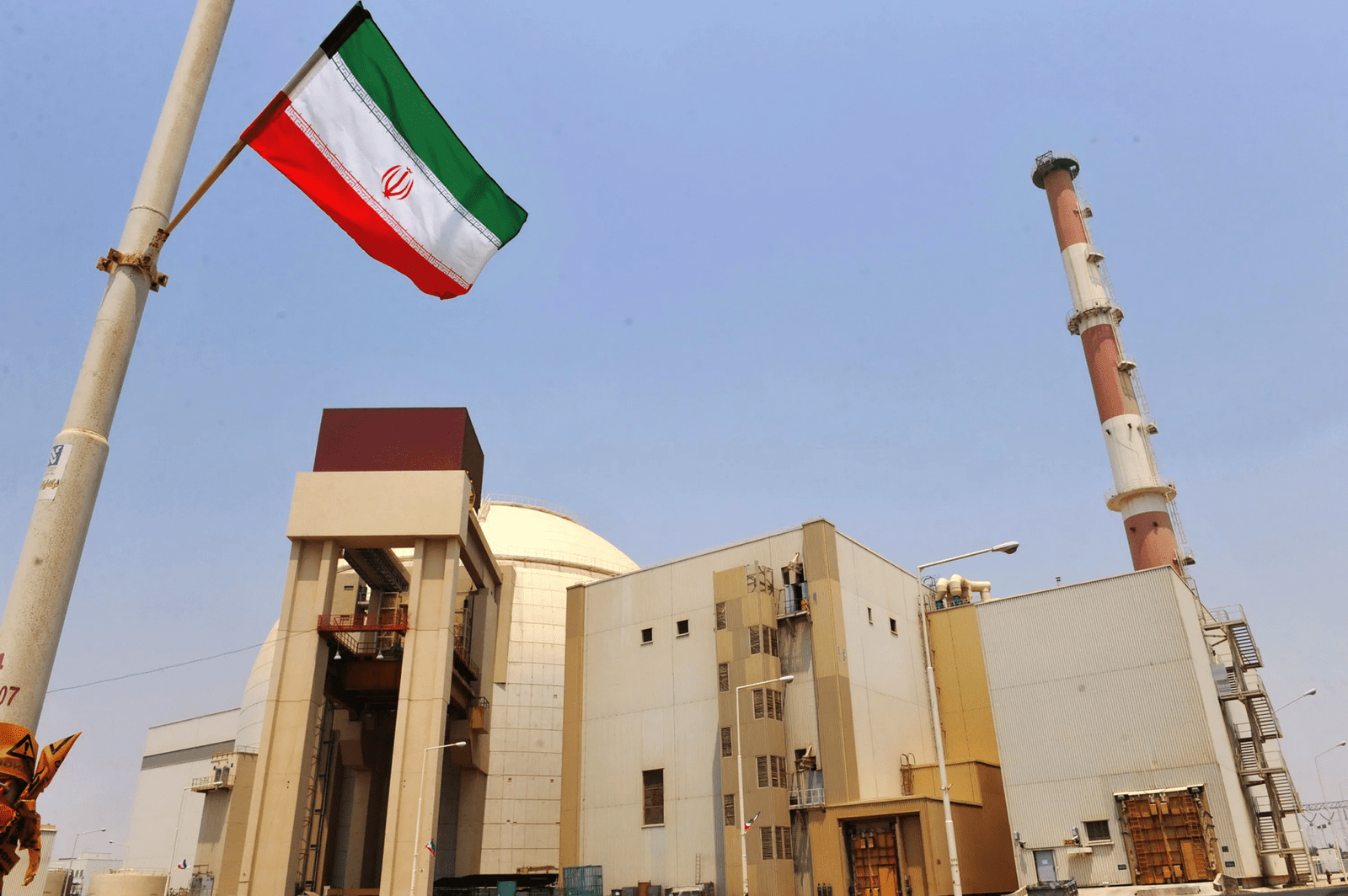

Few operations in contemporary warfare are comparable to the task of disabling a nuclear program buried under mountains and reinforced concrete. Iran’s network of nuclear complexes—Fordow, Natanz, and Isfahan—is among the best protected and most deliberately hidden facilities on the planet. Recent attacks on the complexes served to emphasize not only the technical prowess involved in striking such targets but also the profound strategic challenges confronting military planners.

Iran did not build its nuclear program carelessly. Having observed Israel destroy Iraq’s Osirak reactor in 1981 and Syria’s Deir ez-Zor facility in 2007, Tehran learned from the experience. Its engineers cut facilities such as Fordow into mountainsides, wrapped them in layers of rock and concrete, and encircled them with high-level air defenses. The result is not just an infrastructure that can function, but one that can survive even the best-planned air attack.

Classic bunker-busters are potent, but they are limited. Israel’s deep-penetration bomb arsenal can shatter hardened bunkers, but Fordow lies entombed at depths beyond their penetration. Only America has a weapon in this scope—the GBU-57 Massive Ordnance Penetrator. It tips the scales at more than 30,000 pounds, with its hardened shell enabling it to burrow through dirt and rock before exploding. Defense experts usually explain it less as a bomb and more as a steel drill filled with precision explosives.

But possessing the weapon is half the battle. Getting it delivered is a different kind of challenge altogether. The only aircraft that can deliver the GBU-57 is the B-2 Spirit stealth bomber, a product of decades of design aimed at penetrating the most advanced defenses. Every B-2 can be loaded with two of these huge bombs, traveling hundreds of miles unseen.

During the operation code-named Midnight Hammer, a fleet of B-2s penetrated deep into Iranian territory, dropping fourteen GBU-57s on Fordow in a closely coordinated attack. Supporting aircraft and cruise missiles widened the assault, highlighting the size and sophistication of the operation.

Even so, success is not assured. To bring down a facility such as Fordow, several bombs tend to be required to hit the very same spot to penetrate deeper with each attack. Accuracy is paramount, and the dangers increase with each subsequent run. Experts warn that some rooms might survive, particularly if Iran had strengthened its tunnels or spread out critical elements across multiple subterranean facilities.

A further complication is the threat of contamination. Bombing active nuclear plants poses the danger of releasing radioactive or chemical materials into the environment. There were reports after the attacks of contamination at Natanz and Isfahan, but radiation levels outside the plants stayed within safety limits. Fordow’s depth might have held most dangers, but breaking underground materials is always dangerous.

Military strategists balance these risks heavily, particularly at sites such as Bushehr, where hitting an operating power plant could release apocalyptic fallout—rendering such sites practically invincible.

But the biggest weakness of airstrikes is something no bomb can remove: knowledge. The engineers and scientists who constructed Iran’s nuclear program still possess the know-how to recreate it. Even if a building is leveled, the program can be recreated. At best, strikes give time—maybe a year or two—but cannot remove the capacity permanently.

The strategic implications cascade far beyond the blast areas. The attacks demonstrated that even the most hardened locations are not out of reach, but they also escalated regional tensions and constricted diplomatic space. Iran’s response remains uncertain, with possibilities running from overt retaliation to covertly resuming its program elsewhere. For the world at large, the strikes raise sobering questions about how much military power can actually accomplish against a tenacious enemy.

In the end, the offensive on Iran’s nuclear facilities highlights both the potential and the limitations of contemporary war. Technology enables militaries to strike deeper and harder than ever before, but it cannot rewrite the laws of science, politics, or human resolve. The toughest targets, as it turns out, are not always the ones buried beneath mountains, but the ideas and aspirations that no weapon can annihilate.