The F-35 Lightning II was once the pinnacle of advanced air power—stealthy, networked, and able to provide the United States and its allies with a commanding advantage many years into the future. The jet is at the hub of American and allied air policy today, but its journey has not been smooth. Elevated expense, ongoing reliability issues, and changing needs of contemporary conflict have raised serious doubts as to what the future holds for air supremacy.

The size of the program is staggering. Today, the Pentagon operates approximately 630 F-35s and is looking to increase that to around 2,500 by the mid-2040s. They are supposed to stay operational until 2088 or later. But maintaining this kind of large fleet in the air is no cheap endeavor.

Reports indicate that sustainment expenses increased from $1.1 trillion in 2018 to $1.58 trillion by 2023—a whopping 44 percent increase over five years. Include acquisition costs, and the program is over $2 trillion. Those numbers aren’t theoretical; they have a direct impact on pilot training, fleet availability, and the timelines of other defense priorities.

A lot of the weight of these costs stems from the aircraft’s complexity. Consider the F-35A, the Air Force’s conventional takeoff variant. It runs around $42,000 an hour to operate, well more than the F-16C/D at $25,400 or the F/A-18E/F Super Hornet at $30,400. Gas alone consumes about $4,500 an hour, and the high-tech systems require skilled technicians, tools, and training. Adding in logistics, maintenance, and personnel, one F-35A costs over $5 million a year. Even replacement components are costly, with landing gear costing close to $180,000 and safety sensor modules going over $500,000 per unit.

Confronted with those facts, the Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps have scaled back their expectations. Planned yearly flight time has been reduced by almost 20 percent for the Air Force and almost in half for the Navy. Despite less flying time, availability rates continue to be disappointing. Fixes cost more time than anticipated, and the spare parts backlog increases. The F-35’s stealth paint and closely integrated systems also make maintenance more difficult, typically involving specialty facilities and lengthy work. Nevertheless, despite the aggravation, the airplane provides capabilities no other in the air can match.

The continuous Block 4 modernization program is to hone that edge with over 75 enhancements, such as enhanced missile capability, advanced electronic warfare capabilities, and enhanced target recognition. But what really puts the F-35 apart is the way it processes and shares information.

Its sensor fusion provides pilots with a smooth, 360-degree picture of the battlespace, detecting threats sooner and coordinating with allied forces in an instant. As Maj. Gen. Gina Sabric explained it: the F-35 is “the quarterback of the whole battle,” coordinating operations and leveraging every asset on the field. That transformation has even changed pilot training.

It takes a different type of airman to fly fifth-generation jets—less dependent upon close formation flight, more on individual decision-making. Rather than tight formations behind a leader, F-35 pilots could be miles wide, connected by sensors and encrypted data streams to conduct sophisticated missions as a team. Training previously stressed quick decision-making under pressure, situational problem-solving, and cross-domain coordination of air, land, and sea forces.

Exercises once considered advanced, such as Red Flag war games, are now part of baseline training. But these advancements come at a cost—not only in dollars but in long-term strategy. Dependence on a single manufacturer and the high price of upkeep limit flexibility, especially for smaller air forces that must balance priorities like base upgrades or precision weapons procurement. Even the United States has had to make difficult sacrifices, postponing or cutting other modernization programs to stay on schedule with the F-35.

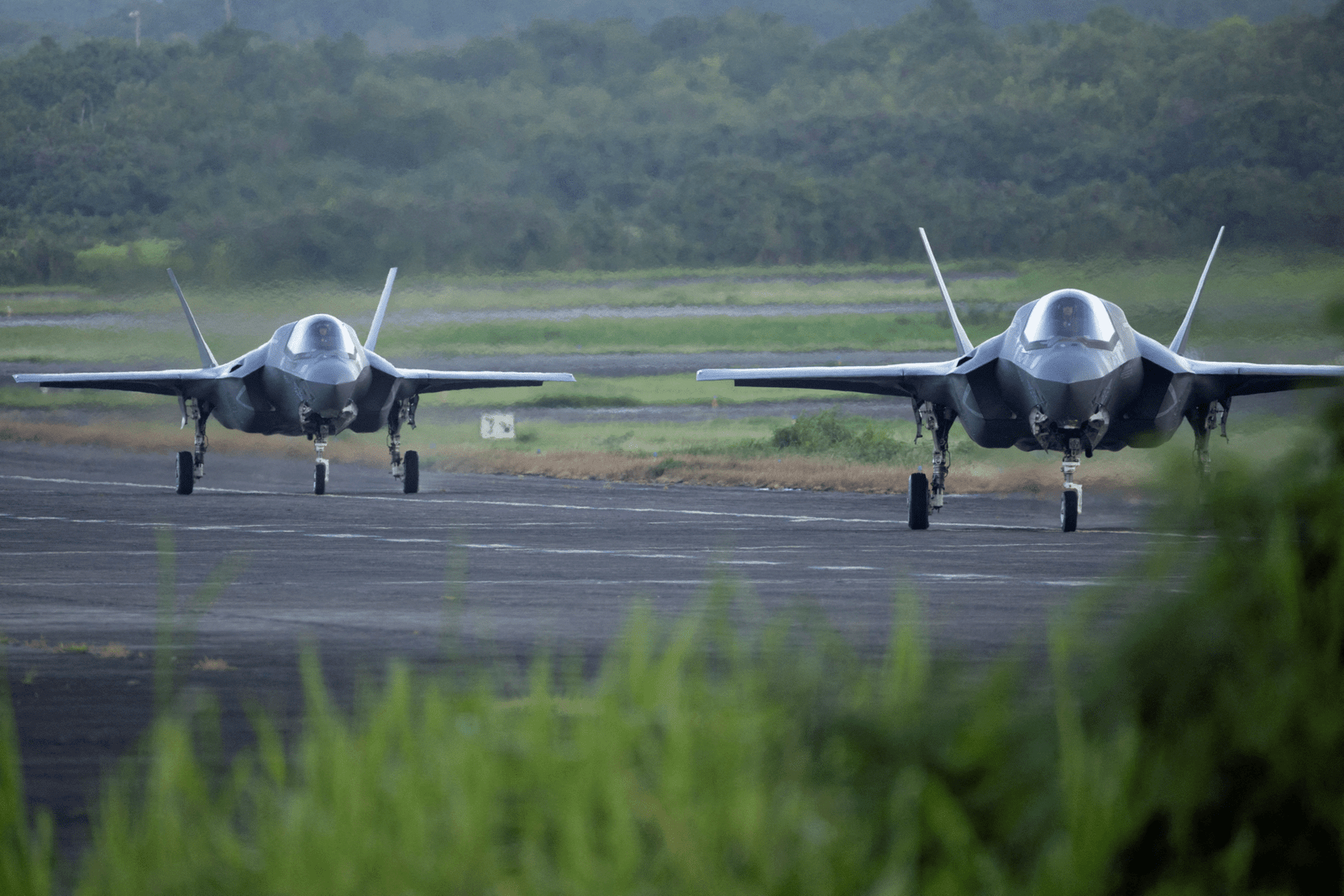

Globally, the jet has established itself as the fulcrum of allied air capability. Hundreds already are operating across Europe, the Middle East, and Asia, and providing interoperability on a scale never before thought possible. Lt. Gen. Michael Schmidt explained that such widespread usage makes the F-35 an actual force multiplier, increasing the scope and impact of allied operations.

Despite the program’s progress, however, its future depends on difficult decisions. Its unparalleled strengths are also its biggest challenges—leading-edge capability encumbered by expense, complexity, and changing mission requirements. Whether the F-35 realizes its potential for shaping air dominance over the next half-century will depend on how leaders reconcile those factors.