During the early days of uncertainty at the dawn of the Cold War, the United States was confronted with a new type of strategic question: how to deploy its bombers deep into enemy skies and return home alive. Jet fighters were getting faster, more lethal, and more in number, poised to overwhelm slower, bulkier bombers. The solution that was suggested was daring and audacious—a “penetration fighter” that would escort bombers on deep penetration missions, shoot its way through enemy defenses, and fly back home safely after striking.

Lockheed’s solution came from its legendary Skunk Works unit, led by engineering icons Kelly Johnson and Willis Hawkins. Their design was the XF-90, a fighter plane that was both powerful and virtually unbreakable.

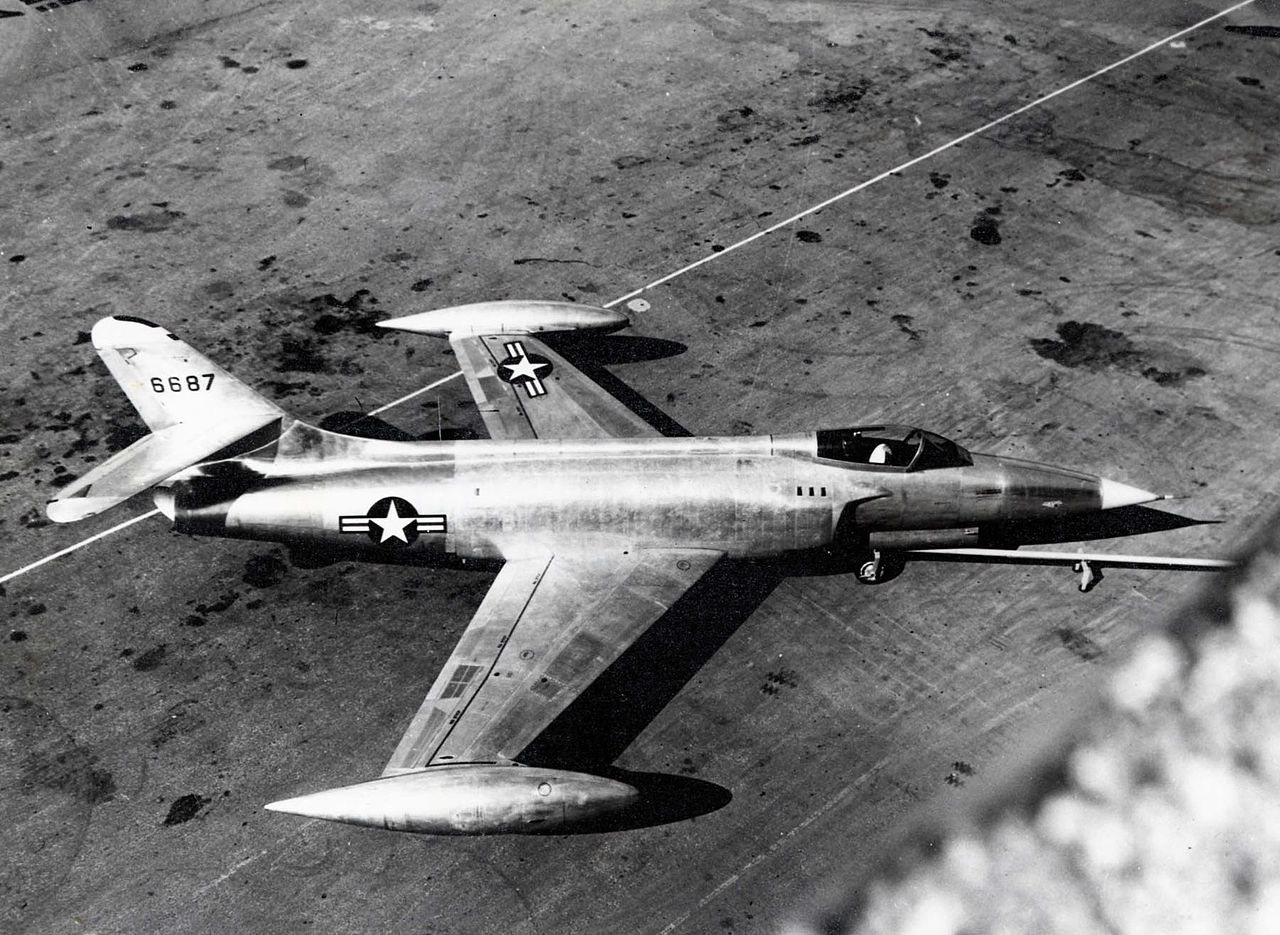

Influenced by the lessons of the previous P-80 Shooting Star, the XF-90 used cutting-edge technology for its time: 35-degree swept-back wings, Fowler flaps, leading-edge slats, and tip tanks to increase its range. Its tail surfaces were also fully adjustable—a breakthrough way ahead of its time and a reflection of the innovative thinking that Lockheed was famous for.

But toughness had a cost. The frame of the XF-90 was constructed of 75ST aluminum alloy—a much stronger material than standard, but heavier as well. That strength would eventually make the aircraft virtually bomb-proof, but it also made the plane heavier than its twin Westinghouse J34 turbojet engines could propel. The result was an airplane with tremendous potential that just didn’t have the horsepower to get there.

On paper, the XF-90 was impressive. It had an estimated top speed of 665 miles per hour, a range of approximately 2,300 miles, and a service ceiling of almost 39,000 feet. However, test flights were a different story altogether. The aircraft was only able to break the sound barrier when it dove, and sometimes needed rocket-assisted takeoffs to get off the runway. It wasn’t as agile or as quick as its rivals, and when compared to planes such as the McDonnell XF-88 or North American YF-93, it fell short.

Later, the Air Force chose the XF-88 as its design of choice, and as strategic needs turned away from long-range escort fighters, the XF-90’s mission dissipated. But though its military life was over before it started, the XF-90’s tale was only just beginning—one forged not in combat, but in perseverance.

One was transferred to the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics for stress testing, and the other was shipped out to the Nevada Test Site to be subjected to nuclear blasts. What ensued made the XF-90 a legend in endurance.

Following a one-kiloton explosion, the plane came out with mere cracks. A second explosion—33 kilotons—broke the nose but wasn’t enough to annihilate the plane. Even a third, 19-kiloton explosion ripping off the tail didn’t annihilate it. Engineers subsequently determined that following the initial explosion, it would have taken more than 100 hours of repair to get the XF-90 flying once more. For an airplane exposed to atomic flames, that was nothing short of miraculous.

Decades later, the radiation-battered hulk of the XF-90 was salvaged, decontaminated, and lovingly restored. Today, it proudly sits at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio—a testament to Cold War experimentation, perseverance, and engineering courage.

The XF-90 might not have seen battle, but its impact extended far beyond its brief service life. What was learned from its design and testing went directly into the development of future Lockheed aircraft, most significantly the high-performance F-104 Starfighter.

Ultimately, the XF-90’s legacy is one of resilience, not failure. It showed that innovation is often a result of trial and error, and that even an airplane considered “unsuccessful” can be a game-changer. Assembled to withstand the unthinkable, the XF-90 stands as one of the hardest jets ever built—a vehicle that literally endured nuclear flames and yet still would not crack.