When an airplane crash occurs, finding answers is suddenly both imperative and intimate. Relatives, survivors, and investigators alike desire to learn what happened—and why it occurred. In such times, the black box is a silent but potent eyewitness, providing an unbiased chronicle of the last moments before disaster. These machines, technically called the flight data recorder (FDR) and cockpit voice recorder (CVR), are designed to withstand the worst—catastrophic crashes, raging fires, even being submerged underwater—so that they can save the tale that must be told.

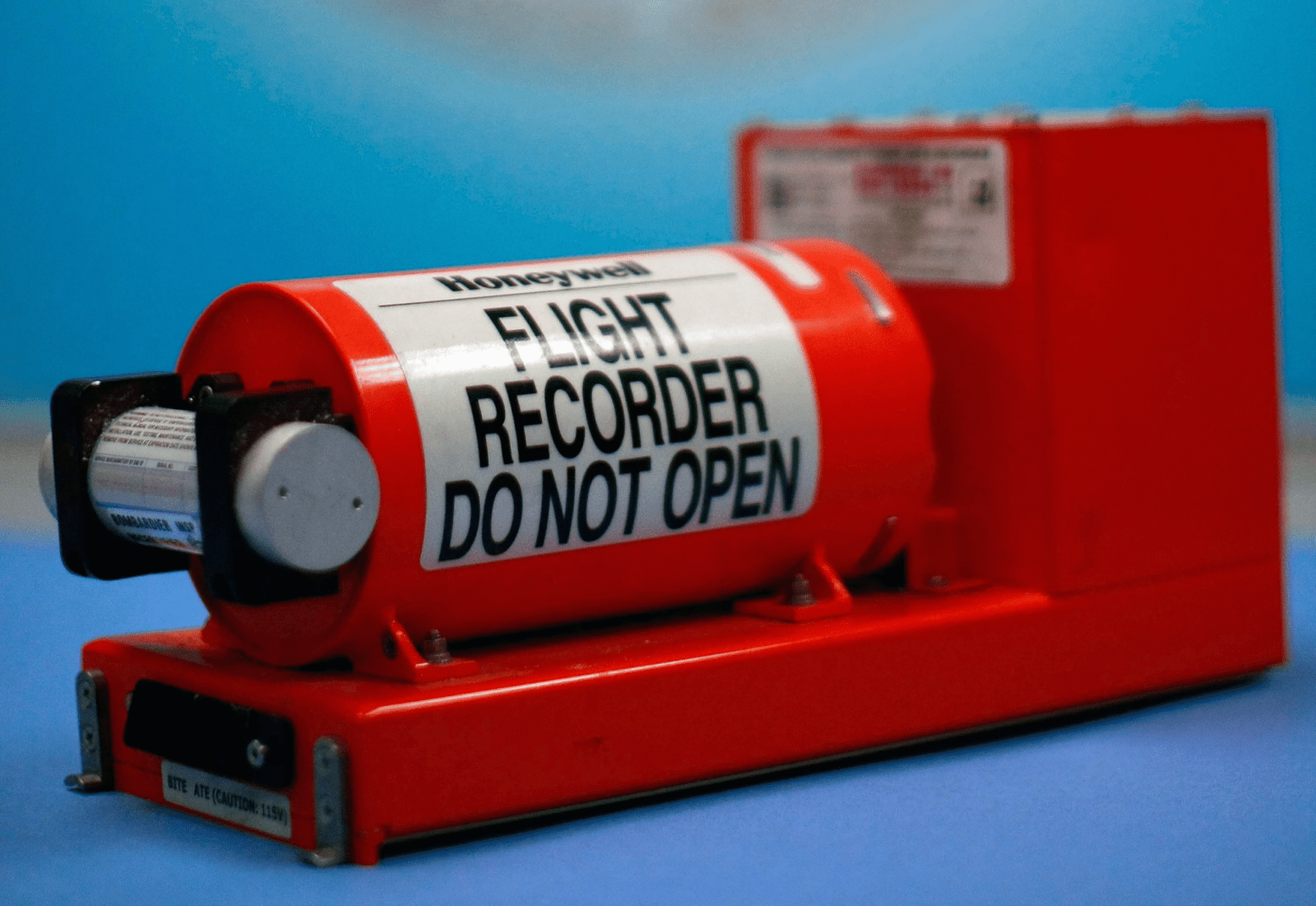

A black box is essentially composed of two important parts that collaborate. The FDR records dozens of technical information about the flight, such as altitude, speed, direction, and how the engines were running. It holds as much as 25 hours’ worth of flight records. The CVR, meanwhile, records the past two hours of cockpit voice—IFF transmissions between the pilots, ambient noises, and warnings. Combined, they provide a comprehensive chronology that assists investigators in reconstructing precisely what occurred in those final hours.

All this information is invaluable in determining why a crash occurred. They employ it to establish whether the accident resulted from mechanical malfunction, human action, or external causes such as adverse weather or bird collision. In court cases, data from black boxes tends to be a major piece of evidence and determines the culprit—be it the airline, the aircraft manufacturer, or someone else. As law firm Callahan & Blaine says, “Black box data is one of the most valuable tools in uncovering the causes of plane accidents” and is invaluable for creating solid cases and prosecuting the correct individuals.

It is not always simple to recover and analyze black box data. The units are commonly found to be buried in wreckage, well down in hazardous locations that make retrieval all but impossible. Even when they are recovered, technical problems—such as broken connectors, corrupted files, or lost parts—can make it difficult. After the crash of Jeju Air, for example, South Korean investigators had to send a crashed flight recorder to the US because they were unable to extract the data from there. As South Korea’s deputy civil aviation minister, Joo Jong-wan, said, “The damaged flight data recorder is found to be unrecoverable for recovering data here.” Such types of complications can delay investigations and add to the suffering of families waiting in vain for an explanation.

There are also serious ethics and laws involved, especially where cockpit voice recordings are concerned. The tapes capture not just technical data—they also capture the final moments in the cockpit, and occasionally even the final words of the crew. Judges and investigators need to weigh their need for transparency against the right to privacy and the emotional cost on victims’ families. It is for this reason that cockpit voice recorder (CVR) data is handled with great care, access to which is heavily restricted, and released in sparingly published measure.

Despite these difficulties, data brought back from black boxes endure. Every question provides lessons that can lead to aircraft design changes, pilot training revisions, and alterations to safety procedures. These are for accident prevention. Experiences of families are corroborated by the data, aid legal cases, and—most importantly—offer the closure needed to recover.

Active cases prove just how important this information is. At the Air India crash investigation, black box tapes are reconstructing critical information, such as when fuel cutoff switches were engaged and emergency systems malfunctioned. The experts said that the crash might have been averted if the aircraft had been cruising higher, but only the data can confirm the entire picture. Also, in the Jeju Air crash, officials are looking at to cockpit voice recorders and flight data to explain why the landing gear collapsed and how the crew responded to those last couple of seconds.

As technology in aviation increases, so does the black box. Recorders today are equipped with higher storage, longer battery life, and even real-time streaming capabilities. On the horizon, technologies like machine learning and predictive analytics can help airlines identify problems earlier so that they don’t escalate into emergencies. Still, no matter how sophisticated the devices are, the objective does not change: to capture the truth, hold individuals accountable, and guarantee flight safety for everyone.

In the skies, black box data is not only a gadget—it’s a bridge between tragedy and understanding. It ensures that even after tragedy strikes, the voices of those on the plane are never silenced. Instead, they work towards creating a safer tomorrow for all who fly.