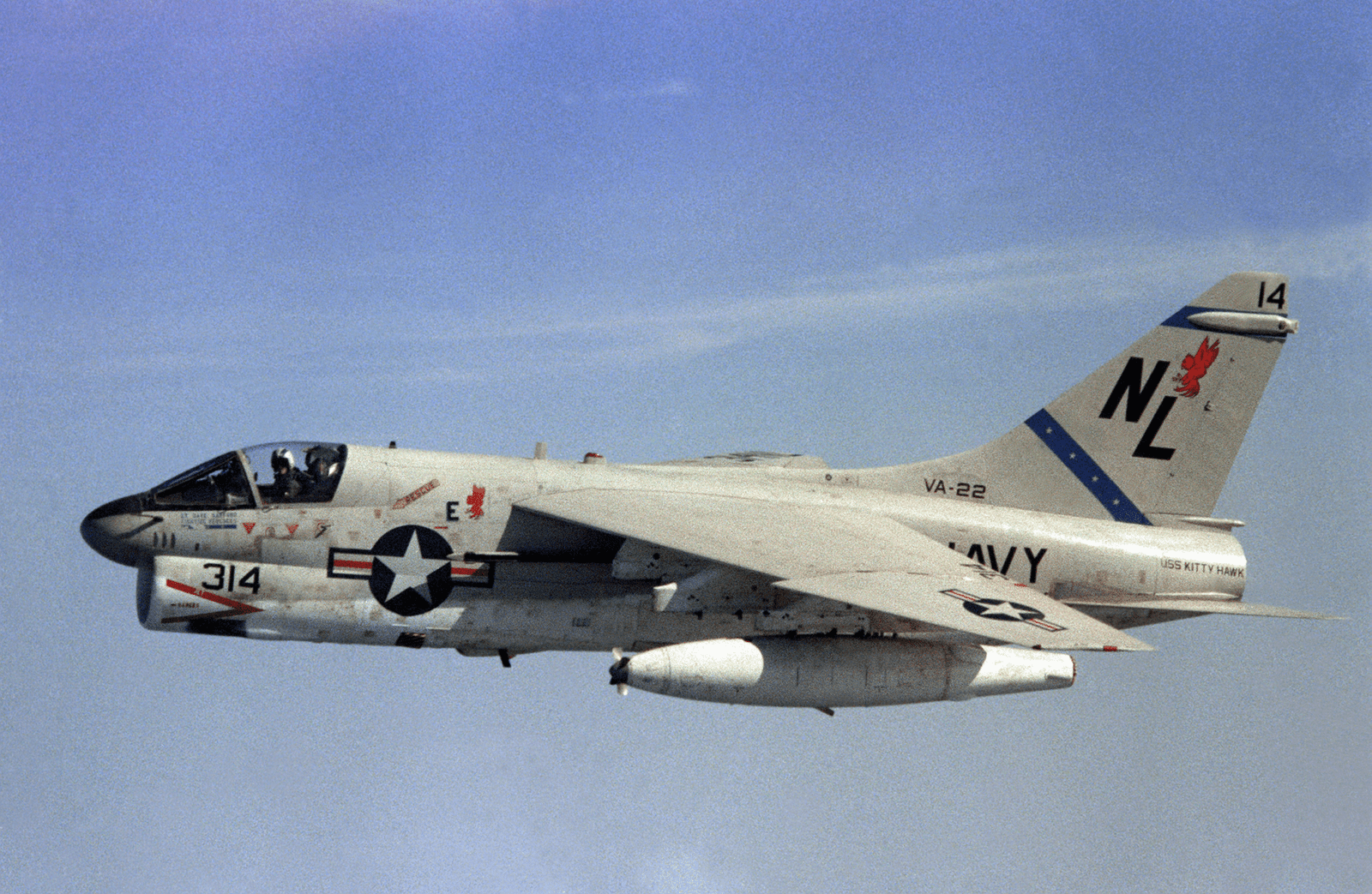

The 1960s were a decade in which jet planes were racing to set speed records and gain altitude, but in the midst of this search for speed, there was a more subdued revolution in progress. The A-7 Corsair II was a subsonic attack aircraft that became one of the most reliable and capable tools of U.S. military aviation without making a splash. It never got anyone’s attention with speed or visual flash, but its usefulness, stable flying qualities, and reliability made it one of the staple workhorses of U.S. air power for well over a quarter century.

The A-7 came about when the Navy was recognizing the limitations of increasingly sophisticated and expensive high-speed fighters. The A-4 Skyhawk had been used by attack squadrons for many years, but the Navy wanted something with more range, more ordnance capability, and yet remain easy to maintain and inexpensive. In 1963, they asked for a design on an existing plane to minimize time and money, and this task was assigned to Vought Aircraft, legendary manufacturers of the WWII F4U Corsair.

Under the leadership of John Russell “Russ” Clark, designers took the F-8 Crusader and shortened its fuselage, did away with the variable-incidence wing, and substituted the afterburner engine with a more efficient turbofan. The result was similar to a mini Crusader but even better than expected in performance and ability.

The A-7 excelled through practical innovation. It was the first U.S. fighter with a heads-up display (HUD), which allowed pilots to see critical flight and target information without looking down. Its avionics suite, such as the AN/APQ-116 radar and its variants, permitted precise strikes even in tough weather, and digital bombing computers provided a level of precision never previously enjoyed by American strike aircraft. Such capabilities put the Corsair II at the forefront.

The Air Force A-7D used the Allison TF41-A-1 engine, a Rolls-Royce Spey license-built turbofan, with aerodynamic improvements like a greater wingspan for more lift and control. It had a combat radius of over 1,200 miles and was capable of carrying over 15,000 pounds of ordnance on eight wing pylon-mounted stores. The A-7 could utilize a broad range of weapons, ranging from standard bombs and cluster bombs to guided Walleye bombs and Maverick missiles.

Despite being subsonic, soon pilots adored the A-7 for its stability, responsiveness, and agility—attributes far more valuable than high speed in low-altitude fighting around North Vietnam. Its rugged construction, armored cockpit, and redundant systems enabled crews to fly dangerous missions and return unscathed, mission after mission.

In the Vietnam War, Navy and Marine A-7s flew more than 97,000 combat sorties at a loss of only 54, and the Air Force counted nearly 13,000 sorties at six losses, illustrating the ruggedness of the aircraft.

The Corsair II proved its worth again in later conflicts, from Grenada and Panama to sorties over Lebanon, Libya, and the Gulf War. Its ability to perform both close air support and interdiction made it versatile and trustworthy, often outperforming flashier aircraft in bombing accuracy and payload capacity.

Throughout its career in service, the A-7 evolved continuously. Early A-7A’s were improved to the A-7B and A-7C, with more powerful engines and avionics. The Air Force’s A-7D got an improved engine, better navigation, and the M61 Vulcan gun. The Navy’s A-7E eventually became the most advanced one with modern avionics and smart munition compatibility. Even globally, Greece, Portugal, and Thailand sold the airplane well into the 21st century.

Another important advantage of the A-7 was cost-effectiveness. At a little over $1 million per aircraft in the 1960s, it was much cheaper than aircraft like the F-4 Phantom. Its non-afterburning engine consumed much less fuel, and maintenance crews enjoyed its straightforward design, which was easier to fix and more quickly and reliably than its predecessors.

In hindsight, the A-7 Corsair II is a watershed moment in the history of strike aircraft. It demonstrated that combat effectiveness isn’t necessarily synonymous with speed or spectacle. Even though it was retired in 1991 and its final flight in Greek operational service in 2014, the Corsair II remains sentimentally beloved by pilots, maintenance crews, and aircraft enthusiasts everywhere for accomplishing impressive missions without ever having to break the sound barrier.