The Lockheed P-38 Lightning was not only a fighter—it was a daring departure from the conventional, a weapon that combined aggressive engineering with fighting prowess in a fashion that no other plane of World War II quite succeeded. Its history is one of innovations, flexibility, and the type of legacy that continues to make heads turn among military historians and plane enthusiasts.

Reinventing the Fighter Blueprint

In 1937, Lockheed was commissioned to design a high-speed interceptor that would climb quickly, strike hard, and fly well at high altitudes. Rather than modifying current models, however, chief engineer Hall Hibbard and a young Clarence “Kelly” Johnson returned to the drawing board.

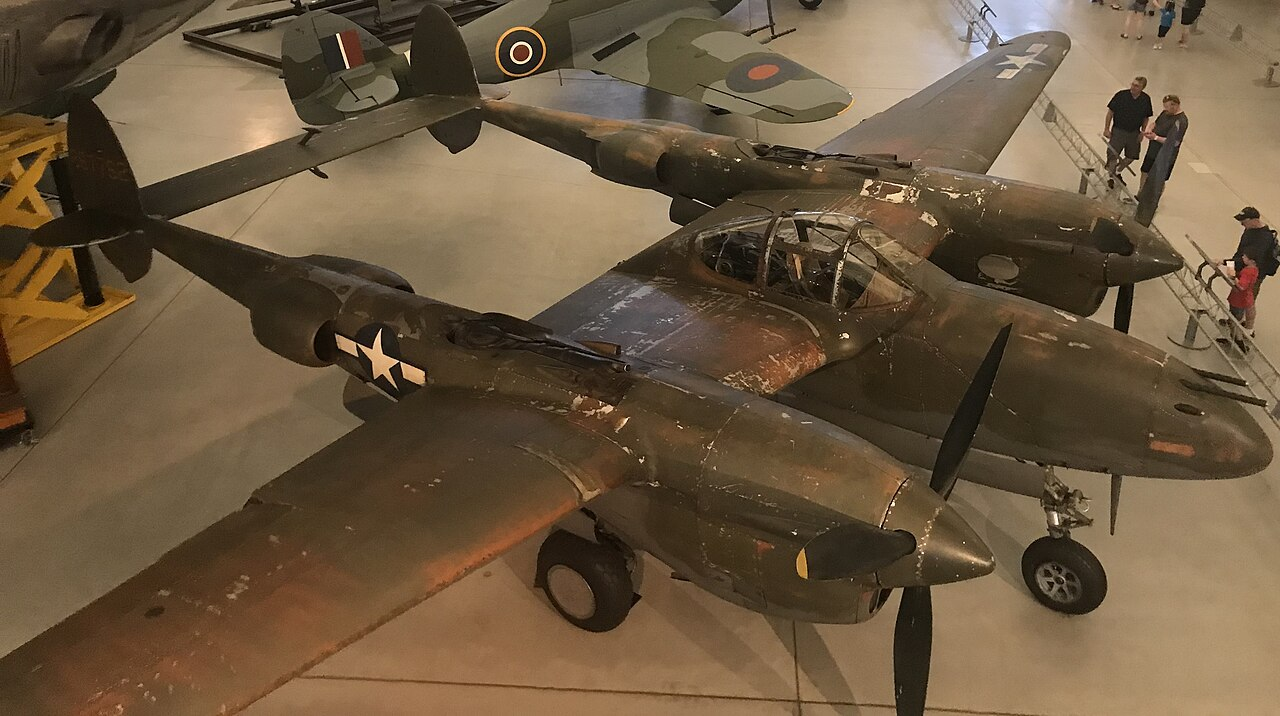

The outcome was something entirely new: a twin-engine, twin-boom fighter with a tricycle undercarriage—a radical change from the norm of the day, which was single-prop tail-draggers. Equipped with four .50-caliber machine guns and a 20mm cannon in the nose, the P-38 could concentrate accurate firepower without suffering from convergence problems inherent in wing-mounted guns.

Two engines provided it with safety and power. Their counter-rotation eliminated torque effects, providing pilots with improved stability on takeoff and in sharp turns. Among the numerous brains behind its creation was Mary Golda Ross, a pioneering Native American aerospace engineer who would go on to influence Lockheed’s most classified projects.

A Learning Curve in the Sky

Of course, revolutionary designs have their hiccups. The P-38 required its pilots to perform a new level of sophistication—systems management, emergency procedures, and high-speed flying far more than what was experienced by American pilots. Training crashes were all too frequently seen in the early days, and the plane’s complexity was also a challenge for ground crews.

In Europe, the Lightning faced further growing pains. Misconfigured engines for different fuel blends, poor cockpit heating in cold conditions, and a lack of experience with twin-engine combat flying made early missions difficult. But Lockheed engineers and Army Air Forces crews kept tweaking, learning, and refining the aircraft.

Trial by Fire: Combat in Two Theaters

The P-38’s baptism of fire in 1942 over Iceland, where it recorded the first U.S. air-to-air kill of the war. In the Mediterranean and North Africa, it escorted bombers and dived with Germany’s Bf 109s. But it was on the Pacific’s extensive, island-hopping campaigns that the Lightning got into stride.

With its range and firepower, the P-38 was the perfect airplane for Pacific operations. The Lightning could cover vast distances of ocean, duel Japanese fighters at high altitude, and return its pilots home—even with a lost engine. Aces such as Richard Bong and Thomas McGuire accumulated dozens of kills flying the Lightning.

John A. Tilley, a pilot who was one of them, remembered how the P-38 could out-turn quick Japanese planes such as the Ki-43 “Oscar” in the right circumstances. Its odd flight characteristics—partially due to the twin booms and counter-rotating props—made it a surprisingly agile dogfighter.

Operation Vengeance: A Mission for the History Books

Among the most risky aerial operations ever undertaken by P-38 pilots in April 1943: the assassination of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, mastermind of Pearl Harbor. After cracking Japanese codes, U.S. intelligence identified his flight schedule.

The only plane that had the range to intercept was the P-38. Making a low and long run down hundreds of miles of open water, the Lightning pilots performed a perfect ambush. Yamamoto’s killing was a severe psychological shock to Japan—and a tribute to the P-38’s unparalleled reach and power.

Heroes in the Cockpit

Regardless of how sophisticated an aircraft is, it’s those who pilot it that give it life. The P-38 required talent and courage in equal proportions. From Dick Andrews, who risked his life to make an emergency landing behind enemy lines to save a fellow pilot, to Charles Lindbergh—who, as a civilian—taught combat fuel-saving methods to P-38 pilots, the stories about the Lightning are human and uplifting.

Pilots’ and units’ reunions, such as the 82nd Fighter Group Association, highlight how strong the relationships were among these men. Major Andy Caluoun, discussing their legacy, focused on how a celebration of these veterans is essential to appreciating the roots of today’s airpower.

The Aircraft That Left Its Mark

More than 10,000 P-38s were produced, flying over 130,000 missions and downing more enemy aircraft in the Pacific than any other U.S. fighter. It also played a crucial role in photo reconnaissance, capturing the majority of Allied imagery over Europe.

With its innovative design—guns on the nose, twin engines, and tricycle landing gear forward—the Lightning established the foundation for generations of fighter design innovation. Its legacy is not only to be found in museums and history texts, but in every contemporary multi-role fighter that places a premium on speed, firepower, and range.

As has been said by test pilot Colonel Ben Kelsey, the Lightning “would fly like hell, fight like a wasp upstairs, and land like a butterfly.” That passion—a combination of ferocity, elegance, and audacity-is—is still what we look for in the greatest combat aviation.