When people talk about precision-guided bombs, they usually jump straight to laser-guided weapons or GPS strikes from recent wars—maybe something from Desert Storm or more modern-day footage we’ve seen on the news. But what many don’t realize is that the story of “smart bombs” goes way back, right into the heart of World War II. And no, the initial guided bombs weren’t produced in American laboratories. They were produced in Germany during the turmoil of the 1940s. The Henschel Hs 293 and the Ruhrstahl Fritz X weren’t merely cutting-edge—they were the start of a completely new era in naval warfare.

Chasing the Dream of the “Smart Bomb”

Even when computers and satellites were not yet in the equation, the minds of the military were already envisioning bombs that could think—or even guide themselves. Blasting a moving vessel from the air was not only hard to do; it was almost an art. Torpedoes and dive bombing demanded precise flight, steel nerves, and even with that, the chances weren’t high. So the dream was straightforward in idea but difficult to implement: what if you could guide a bomb once you’d released it?

Several nations were messing around with the possibility. The Americans and British experimented with early radio-control ideas between the wars, but none of their work made it out of the drawing board in any significant capacity. Germany went further. Although their V-1 and V-2 missiles are more notorious, those weren’t precision weapons—they were terror weapons, targeted more at cities than at individual targets. But the Hs 293 and Fritz X? Those were something else. They were guided. They were targeted. And they worked.

Hs 293: The Rocket-Boosted Ship Killer

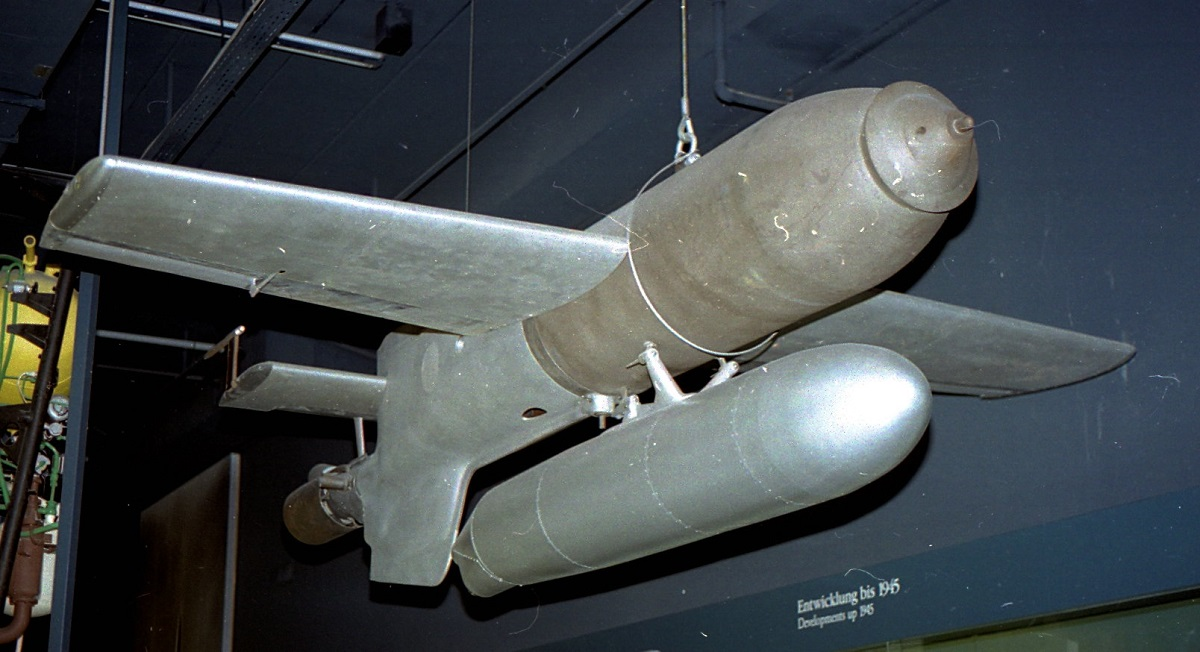

The Henschel Hs 293 was one of those weapons that made you pause and look. Imagine a little airplane thing with a 10-foot wing and a thousand-pound warhead. It wasn’t designed to blast holes in battleships, but for troop ships, freighters, and lightly armored ships, it was lethal. And it didn’t drop—it flew. It had a rocket motor to give it a brief burst of speed and distance, and it could fly several miles after being fired.

Here’s how it was done: a German bomber—a Dornier Do 217, but other planes were employed as well—would ascend to between 3,000 and 5,000 feet, drop the bomb, and then the rocket would take over. The crewman from that time on would steer the bomb manually with a joystick and radio signals, observing the tail lights or flares on the bomb to keep it on course.

The first combat outing of the Hs 293 was in August 1943, against British vessels in the Bay of Biscay. The bombs struck but failed to detonate. Nevertheless, it wasn’t long before it claimed its first victim: two days later, one sank the HMS Egret, becoming the first vessel ever sunk by an air-delivered guided projectile. But the most deadly blow was to be struck in later that year when a supply ship, HMT Rohna, was torpedoed. A thousand or more American soldiers were lost, and it would be the single deadliest attack on U.S. forces at sea for the entire conflict.

Though the Hs 293 was used to attack land targets such as bridges, it never found much success there. Its real significance lay in naval combat, where it caused Allied commanders to rethink their fleet’s defense.

Fritz X: The Battleship Cracker

And if the Hs 293 was designed to destroy smaller vessels, the Fritz X was made to blast right through giants’ armor. Approaching 3,000 pounds and loaded with a 700-pound warhead, it didn’t require a rocket engine. It was released from high altitudes—usually 20,000 feet—and utilized gravity and velocity to cause the damage. By impact, it was traveling at near-supersonic rates.

The Fritz X was handled exactly like the Hs 293—radio-guided by joystick, by flares on the back of the bomb so that the crewman could steer it to impact. And it was ruthlessly effective. In August 1943, the Italian battleship Roma was attempting to surrender to Allied ships when it was hit. A single bomb disabled the ship; a second bomb exploded a magazine. The explosion that ensued was so forceful that it completely shattered a turret completely off. More than 1,300 sailors were killed in a matter of minutes.

The success of the bomb did not stop there. On the Salerno landings in September, Fritz X bombs crashed into Allied cruisers such as the Savannah and Philadelphia, and even destroyed the old British battleship Warspite. Altogether, the bomb destroyed or damaged several warships within weeks. But it wasn’t perfect. The hit rate wasn’t great—perhaps one in five bombs struck a successful blow—and the system depended on ideal conditions: clear skies and a leisurely-moving bomber.

The First Electronic Battlefield

Of course, the Allies weren’t going to sit idly by and let this happen. After they discovered how the bombs were being controlled, they began jamming out the radio signals. This was the beginning of what we today refer to as electronic warfare—jamming by one side, countermeasures by the other, and so on. Germany retaliated with tests of wire-guided bombs, but the point was made. By flying higher and employing jamming devices, Allied forces started to blunt the effect of these feared weapons.

The Legacy of Early Guided Bombs

Ultimately, neither the Fritz X nor the Hs 293 proved decisive in tipping the war’s balance. They had their successes—some of them catastrophic—but their efficiency fell sharply once surprise was lost. Nonetheless, what they stood for was something much greater: the dawn of precision warfare. They were the precursors to the cruise missiles and smart bombs of today. And they brought with them a new type of war involving not only steel and flames, but signals, frequencies, and the intangible field of electronic warfare.

And as certain historians have noted, the Germans might not have won the war with their guided bombs, but they did bridge the gap to a future when striking a target with precision pinpoint accuracy became feasible—and required. All modern strikes, all countermeasures, all combat waged across the electromagnetic spectrum have their origins in those early times over the Bay of Biscay and the Mediterranean Sea. The technology has evolved, but the competition for precision—and the competition to counteract it—is as active as ever.