Of all the untold or half-forgotten tales of World War II, few are quite so unnerving—or so enigmatic-as the disappearance of Japan’s battleship Mutsu. A former symbol of naval power and national prestige, Mutsu’s unexpected demise in 1943 raised as many questions as it answered, and still one of Japan’s most ghostly maritime mysteries.

Mutsu was a product of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s Eight-Eight Fleet Plan—a daring pre-WWI plan to construct an eight-battleship, eight-battlecruiser fleet equal to the great powers. When this plan grew, Japan sanctioned the construction of the Nagato-class battleships in 1916. The second in the class, Mutsu, was commissioned in 1920 and entered service officially the next year. Her commissioning was a national celebration, witnessed by Crown Prince Hirohito and his mother. Partly funded by public contributions, Mutsu was something more than a warship—she was an honor. In the negotiation of the Washington Naval Treaty, Japan struggled to prevent itself from being scrapped and finally won out where other vessels did not.

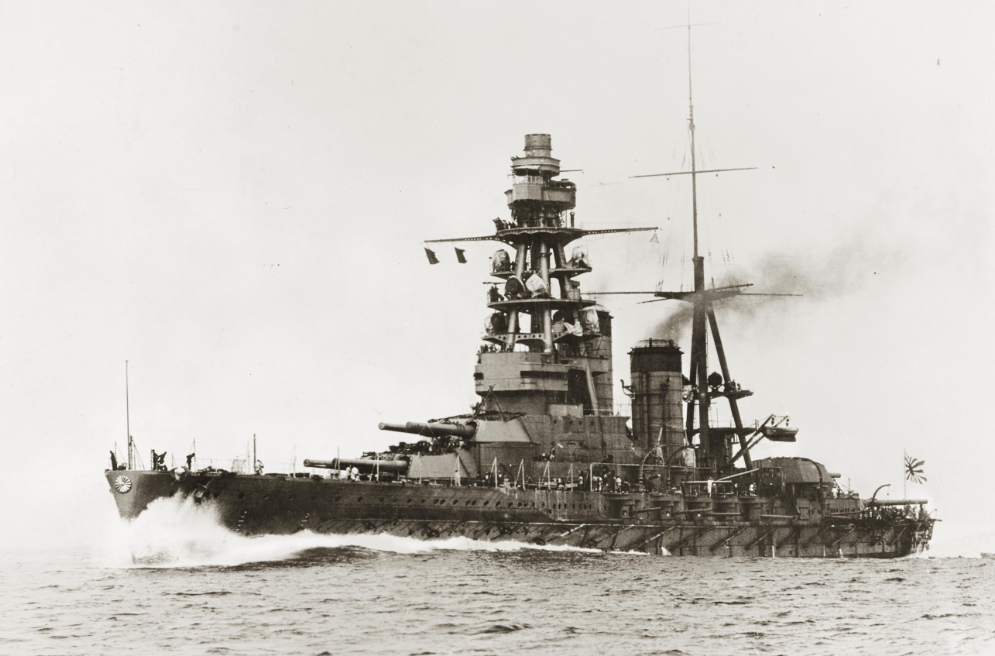

Mutsu was technologically advanced for her time. Naval historian Stefan Draminski writes that the Nagato-class was the first in the world to be equipped with 16-inch guns, marking Japan’s move to lead in quality even if they couldn’t do so numerically when compared to competing fleets. Nagato and Mutsu were redesigned in the 1930s with enhanced armor, propulsion systems, and Japan’s trademark pagoda mast. By the outbreak of the Second World War, Mutsu was still formidable, although rapidly obsolescent relative to the new Yamato-class super-battleships.

For all her firepower and size, however, Mutsu engaged in little combat. She assisted operations at a distance during the Pearl Harbor raid, served as a training ship, and even tugged Yamato. She was at the Battle of Midway but did not engage, and her only combat action was at the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, when her guns fired at American scout aircraft. For the majority of the war, Mutsu was used as a transport and training ship—a huge ship with a diminishing role.

All that changed on June 8, 1943. Anchored at Hashirajima Bay, Mutsu was having more than 100 naval flight cadets and 40 instructors visit for a tour. At 12:13 p.m., a massive explosion rocked under her No. 3 turret. The explosion was so powerful that it cleaved the ship in two. The forward half went down almost instantly; the rear half drifted and burned before going down hours later. Of 1,474 on board, only 353 were saved. Only 13 cadets survived. The enormity of the disaster rocked the Imperial Navy to its foundations.

Panic and concealment followed. Anti-submarine alerts were sent out by the military, but no enemy action was encountered. To maintain morale, the event was declared top secret. Survivors were dispersed to other duties and made to remain silent. Even the loved ones of the fallen were kept in the dark for months. One particularly harrowing example: the widow of Mutsu’s captain, Teruhiko Miyoshi, allegedly wasn’t told of his demise until January 1944—nearly seven months after the vessel sank.

The origin of the blast soon became the subject of rumor. Initially, suspicion fell on the ship’s Type 3 “Sanshikidan” shells, which were kept nearby. These volatile incendiary rounds had a reputation for causing trouble. But the smoke seen by eyewitnesses was red or brown, not the white smoke normally found when these shells exploded. Eventually, the Navy concluded that the blast was the result of sabotage.

They indicated a seaman who had been apprehended for theft and was scheduled for court-martial that morning. He was supposed to have ignited a fire close to the magazine as a diversion, as described by the official account. Few believed this, however. His corpse wasn’t discovered at the time of the initial salvage operations, and his critics suspect that he might have been made a convenient scapegoat.

Other theories point to an internal failure. Although upgraded over the years, Mutsu also had vast stores of flammable material and an old electrical system. A faulty wiring or stray spark could have led to a fire that extended to the magazine. But for a navy already reeling from its inability to keep its hold on the Pacific, to admit such a deficiency would have been catastrophic.

After the war, the truth was elusive. Salvage operations went on for decades, and remnants of the ship—including her crest and a turret—were recovered eventually. In a bizarre irony, the remains of the missing sailor were discovered in 1970. Even that, however, did not solve the central mystery.

The Mutsu Memorial Museum today is a memorial to those who were lost and an echo of how quickly pride can translate into disaster. Her tale is a question of military secrecy, responsibility, and the unspoken cost of war. Was Mutsu torpedoed by sabotage, by accident, or by design flaws not dealt with for too many years? We may never know. But her legacy continues as one of the most disquieting—and humane—tales to have come out of Japan’s naval history.