During the Cold War, speed wasn’t simply about coming out on top—it was a matter of survival and strategic advantage. The United States and the Soviet Union were engaged in a fierce contest, vying with one another to be technologically superior, and nowhere was this more evident than in the field of air reconnaissance. To fly fast and high was the ultimate objective, enabling each side to collect intelligence deep within enemy skies without risking pilots to an undue extent.

The U-2, sarcastically known as the Dragon Lady, was America’s first daring foray into high-altitude reconnaissance. Designed by Kelly Johnson and the renowned Lockheed Skunk Works, the U-2 was able to fly above 70,000 feet, well out of the range of most Soviet interceptors and missiles—at least temporarily. While groundbreaking for its time, the U-2’s aluminum construction and low speeds exposed it once Soviet air defenses matured.

The shooting down of a U-2 in 1960 over Soviet territory was a harsh wake-up call, revealing the aircraft’s limitations and fueling a crisis that compelled U.S. intelligence to reconsider its airborne tactics. As documented by sources, on May 1, 1960, a U-2 was downed over the USSR, initiating the infamous U-2 Affair. Later, in 1962, during the Cuban Missile Crisis, a U-2’s photos were instrumental in verifying that Soviet nuclear missiles were present on the island.

Out of this challenge was born the A-12 Oxcart—an ultra-covert, supersonic plane built by Lockheed’s Skunk Works under the guidance of the fabled Clarence “Kelly” Johnson. Intent on flying higher and faster than anything yet, the A-12 was constructed primarily of titanium, not because it was convenient to work with, but because it was the only metal hardy enough to endure the searing heat produced at speeds over Mach 3.

The A-12 made its first flight in April 1962 at the secret Groom Lake facility, more commonly referred to as Area 51. As aviation expert Brian J. Barsanti explains, the A-12 reached Mach 3.2 speeds and ascended above 90,000 feet during its short but illustrious career. Although its operational lifespan was brief, the A-12 paved the way for what would be one of the most legendary spy planes ever constructed.

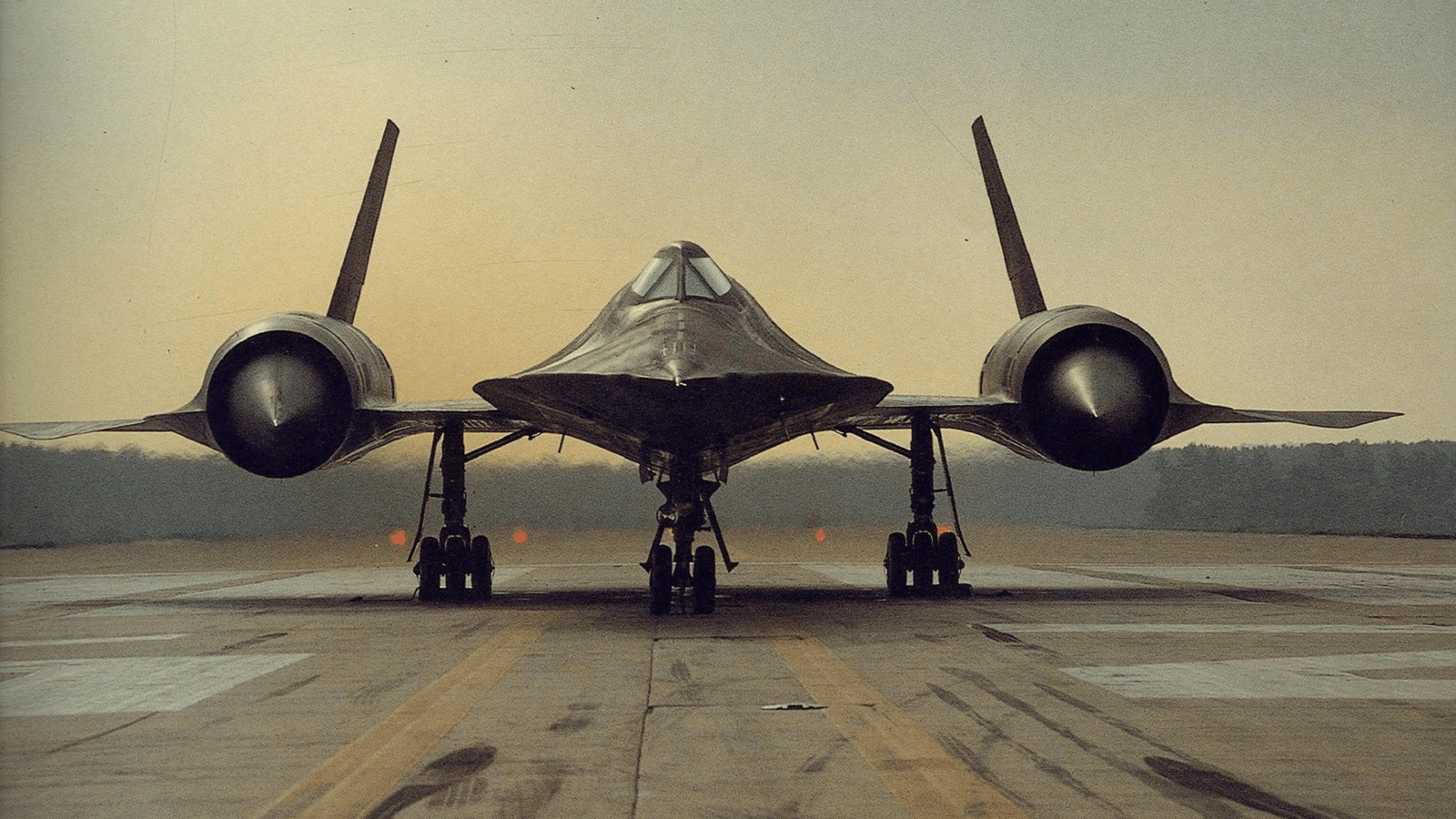

Continuing on the A-12’s success, the SR-71 Blackbird took the envelope even further. Featuring its svelte, black titanium body and sharply angled profile, the Blackbird represented both engineering brilliance and the urgency of the Cold War. It flew as fast as Mach 3.2 and as high as 85,000 feet, effectively beyond the range of Soviet missiles and interceptors.

Its Pratt & Whitney J58 engines were themselves miracles, being able to operate in a mode intermediate between a turbojet and a ramjet at top speed. The black paint of the plane was not selected for aesthetics; it performed a crucial role in dispersing the excessive heat generated from air resistance, earning the aircraft its legendary moniker. The engineers targeted speeds of over 2,000 miles per hour—a capability that fewer planes could achieve, particularly on long flights.

The SR-71’s accomplishments were phenomenal. It might fly across entire continents within a matter of less than two hours, gather intelligence unseen, and just outrun any effort to intercept it. Pilots were forced to wear pressure suits similar to astronauts, a requirement for enduring the extreme altitudes and conditions involved in a mission flight.

Although most of its activities were classified, the SR-71 significantly influenced U.S. intelligence activities and strategic deterrence. As the National Reconnaissance Office has reported, no reconnaissance aircraft in history has had the kind of worldwide reach and impunity as the SR-71, which is one of the fastest jet-powered planes ever flown.

The Soviets attempted to match aircraft such as the MiG-25 Foxbat, which had the same speed capability as the SR-71 at Mach 3.2 but had low range and poor handling, not to mention a huge radar cross-section. Other Soviet designs, such as the Tsybin RSR and the Bartini A-57, sought equivalent performance but were never successful through technical challenges and changing priorities. Elsewhere, new high-speed unmanned vehicles have appeared, such as China’s WZ-8 drone and hypersonic glide vehicles, but none have achieved the same combination of speed, altitude, and versatility that made the SR-71.

As technology progressed, drones and satellites started substituting for many of the duties previously given to high-speed manned aircraft. The CORONA satellite program, for instance, enabled the U.S. to collect critical intelligence from space without jeopardizing pilots and planes. However, satellites cannot provide the sense of urgency and in-flight flexibility of a spy plane that can alter course or react to an emerging threat.

The quest for speed is not yet complete. The U.S. is also continuing to advance hypersonic capabilities, with programs such as the SR-72 “Son of Blackbird” to fly at over Mach 6. Although more advanced systems are just emerging, they include novel propulsion systems like GE Aerospace’s dual-mode ramjet engine using rotating detonation combustion.

These offer even more speed and efficiency. Its design can potentially propel aircraft over Mach 10, an enormous improvement over traditional jet engines. The SR-72, as an envisioned unmanned aircraft with a turbine-based combined cycle powerplant, is the future of the constant pursuit of air speed and height.

The history of the SR-71 and those that came before it is not just a story of incredible speed—it’s a testament to human engineering, the need for strategic dominance, and the incredible measures that countries take just to be able to control the skies.