Hypersonic missile technology is revolutionizing the face of global military power at a frenetic pace. These weapons provide a previously unimaginable combination of sheer speed, highly accurate maneuverability, and strategic ambiguity. They are not simply faster versions of existing missiles—they are a new era in how militaries operate on offense, defense, and deterrence.

The “hypersonic” is speeds above Mach 5, or about 3,800 miles per hour. For perspective, a commercial airliner cruises at a bit under 600 mph. At that speed, a hypersonic missile would be able to strike from New York to the nation’s capital in less than four minutes. But magic isn’t speed—it’s maneuverability. Hypersonic missiles can make sharp turns while flying, which renders them nearly impossible to track or intercept.

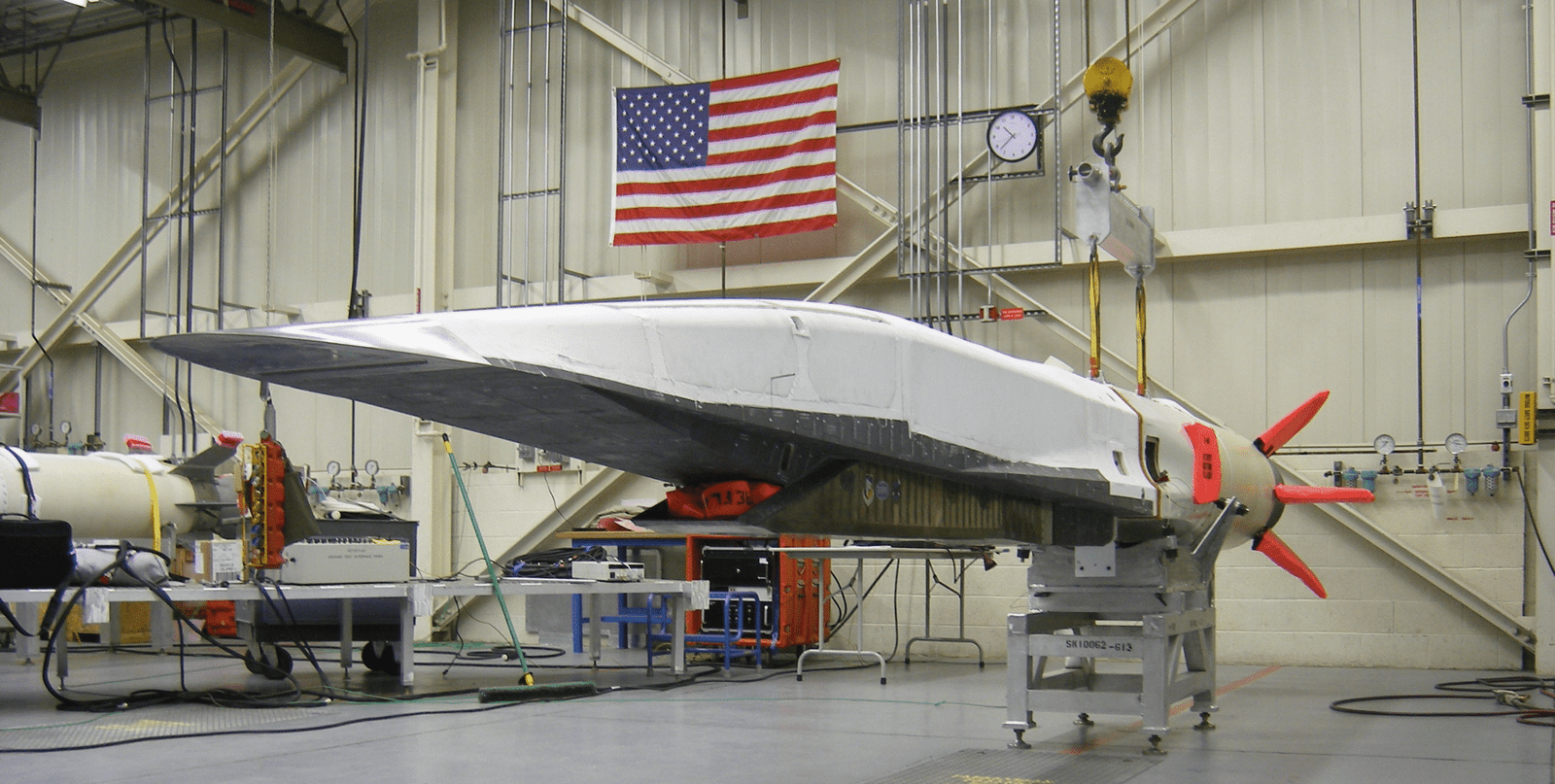

There are three broad categories of non-ICBM hypersonic weapons: aero-ballistic missiles, glide vehicles, and cruise missiles. Aero-ballistic missiles are launched from aircraft, reaching hypersonic speeds before flying on a partially ballistic trajectory to the target.

Hypersonic glide vehicles are launched to the upper atmosphere, then glide on a wave-like trajectory to the destination. Scramjet-powered air-breathing hypersonic cruise missiles can sustain high-speed flight in the atmosphere and provide convenient launch arrangements at potentially lower expense.

Likely the most-widely-discussed currently deployed is the Zircon missile, which is on board Russia’s Admiral Golovko, a Project 22350 frigate commissioned late in 2023. The Zircon flies many times the speed of sound and can cover distances to targets up to approximately 900 kilometers.

In its initial operational exercises, the Golovko showcased the Zircon’s capability in sensitive waters, sending a strong message regarding hypersonic missiles’ dislocating capability. The multi-mission-capable Gorshkov-class frigate that can carry out surface-to-ship, surface-to-submarine, and air-defense missions is representative of why hypersonic missiles are setting the pace of naval strategy in the new era.

The United States has not been blind. Hypersonic missiles are a difficult place to defend against—too high for traditional cruise missile defenses but lower than intercontinental ballistic missiles—difficult to see and with limited warning time down to minutes. In response, U.S. forces are investing in next-generation space-based sensing and layered defense technologies to detect and kill such threats before they can hit their target.

Strategic implications extend far beyond the technology. Hypersonic systems capable of nuclear payload, for instance, limit an opponent’s response window to mere seconds in deciding whether or not an incoming missile has conventional or world-ending cargo. That stress moment increases the likelihood of miscalculation or surprise escalation.

There are constraints, naturally. Hypersonic missiles are costly, high-technology, and won’t be made in quantities. Their strongest asset is to attack highly valued, highly protected targets—like aircraft carriers or strategic installations—better than swarms of conventional attacks.

Deploys them on front-line warships, as well, and it’s revolutionized naval warfare. Speed, agility, and surprise can enable these missiles to penetrate even the most advanced defense systems.

With increasing numbers of nations moving on hypersonic programs, the challenge will be creating stable countermeasures to missiles that are moving faster than diplomacy or traditional defenses can react. The next decade will remake the rules of war above Mach 5, and the strategic decisions of today will determine the nature of warfare for decades to come.