Air superiority has always been about extending boundaries—sometimes defying physical boundaries, such as the sound barrier, and sometimes imagining what a fighter airplane could even be. Exactly that was the concept behind Boeing’s X-36 project during the 1990s. Though it never went into service, this tiny experimental aircraft defied conventional fighter design and quietly laid the groundwork for what would become the U.S. Air Force’s sixth-generation stealth fighter, the F-47.

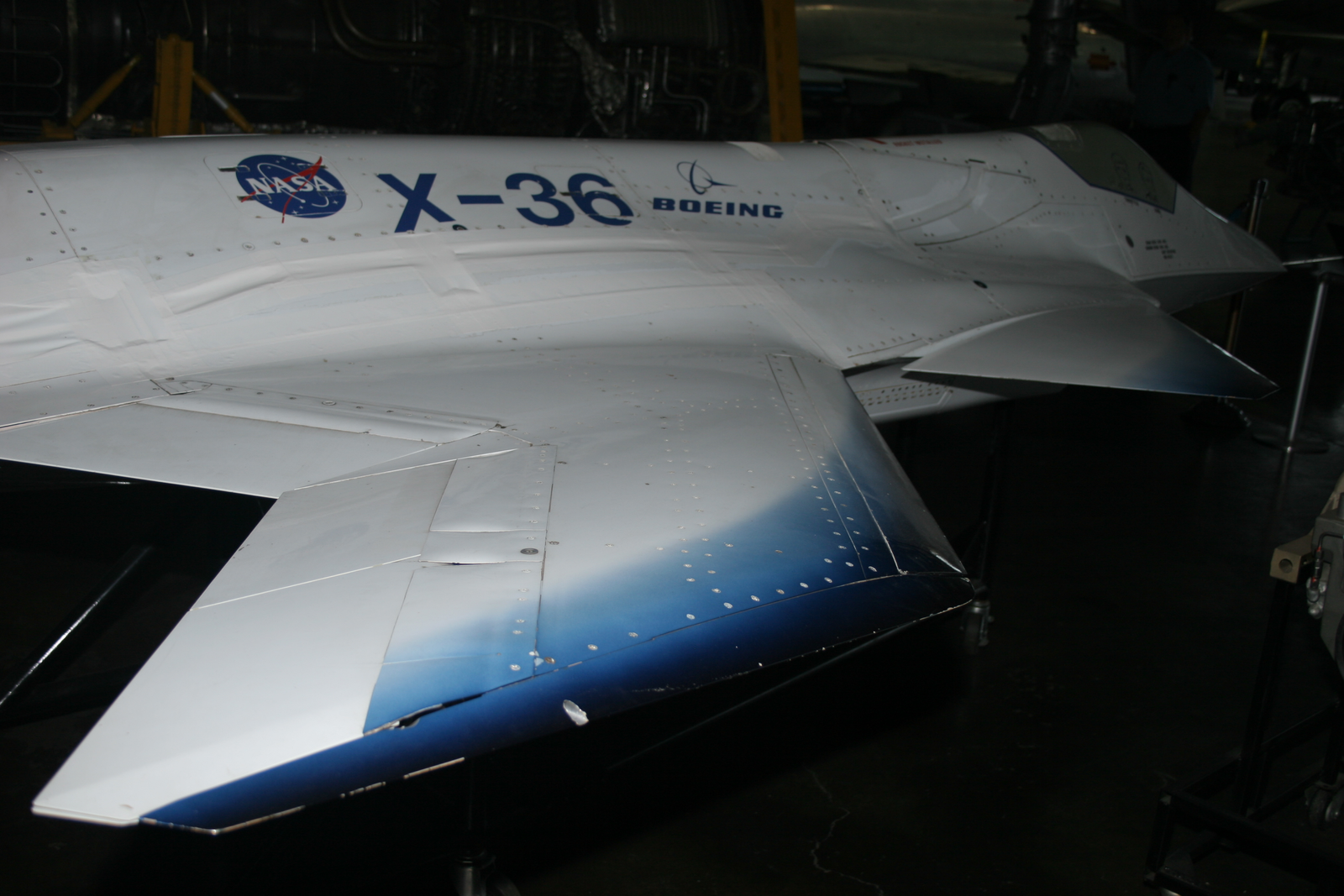

In the mid-1990s, McDonnell Douglas Phantom Works, now a division of Boeing, partnered with NASA to try a radical idea: was it possible to make a jet fly without a vertical tail and yet be completely controllable and agile? The X-36 was the result of that partnership as a striking, petite prototype, only 28 percent the size of a full-size fighter but loaded with new ideas.

At just 19 feet in length and weighing about 1,250 pounds when fueled, the X-36 was powered by a small 700-pound-thrust F112 turbofan engine. Its power wasn’t in sheer power, however—it was in testing flight control and stealth technology. With no vertical stabilizer and no traditional tail, it employed forward canards and a wide “lambda wing” of a distinctive shape, earning it a look unlike any other aircraft of its era.

Flight testing commenced in May 1997 at NASA’s Dryden Flight Research Center in California. As a scaled model, the X-36 didn’t have a pilot on board. Instead, it was controlled from the ground by real-time video and a fighter-style heads-up display. During only 31 flights, the X-36 accumulated over 15 hours of flight time, achieving heights above 20,000 feet and holding bank angles of 40 degrees or more—a considerable feat for an aircraft lacking conventional control surfaces.

Stability was the biggest problem, as eliminating a tail necessarily made the jet less stable in pitch and yaw. Engineers countered with a sophisticated digital fly-by-wire system that managed its canards, divided ailerons, and thrust-vectoring nozzle. On top of that, pioneering AI flight control software such as the Air Force’s RESTORE program enabled the aircraft to adjust in real time to control problems—a preview of the autonomous and assistive flight systems to come. Despite its compact size, the X-36 was able to handle as well at slow speeds as at high speeds, a balance that few full-scale fighters can match.

While the X-36 never saw operational use, lessons learned from it were long-lasting. Building a full-scale tailless fighter was too costly at the time, and the project was terminated. The knowledge, however, gained in flight control, stealth shaping, and thrust vectoring paved the way for future experimental aircraft, including Boeing’s Bird of Prey and X-45 UAVs, and eventually influenced the F-47 design.

The X-36’s DNA carries over in the F-47, being developed for the Air Force’s upcoming air dominance program. The plane is designed with a wide, tailless fuselage and forward canards, with stealth, agility, and sophisticated systems integration.

The F-47 would, unlike the traditional jet, be used in conjunction with autonomous drones as part of a manned-unmanned team, using onboard sensors and AI-driven systems. What was once considered a radical experiment is now at the heart of the next generation of air warfare.

The X-36 was one of a larger wave of tailless aircraft testing in the midst of an unusually innovative period for U.S. aviation. Boeing’s Bird of Prey tried out extreme stealth shaping, while Lockheed’s X-44 MANTA emphasized delta-wing control without canards.

Other smaller projects, such as the YF-24, also experimented with tailless configurations. All of them provided useful insights into aerodynamics, control, and radar avoidance, but the X-36 was the first to integrate all of these into a single, functioning aircraft.

The X-36 story is a reminder that the most important technology breakthroughs tend to spring from the most radical, most unorthodox concepts. A small, remotely controlled, tailless model may have been a novelty when it was introduced, but it set the stage for planes that are faster, more maneuverable, and more invisible than ever before. As the F-47 heads out on a mission, one can recognize the impact of the X-36 all too well. It might never have fired a shot in anger, but its designs continue to influence the course of American airpower.