Competition in hypersonic weapons is now one of the most conventional military technology competitions of the era. With their competition nations backtracking on their own, the US has been under increasing pressure to get in on the action. The Air Force’s AGM-183A Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon—or ARRW—was meant to be the solution.

A rocket-assisted, air-launched missile to operate in the Mach 5 to Mach 8 speed range, it might provide U.S. forces with the capability to attack high-priority targets well inside defended areas. But its evolution from theory to hardware was a rough ride, learning how to overcome the challenges of fielding pioneering technology into combat.

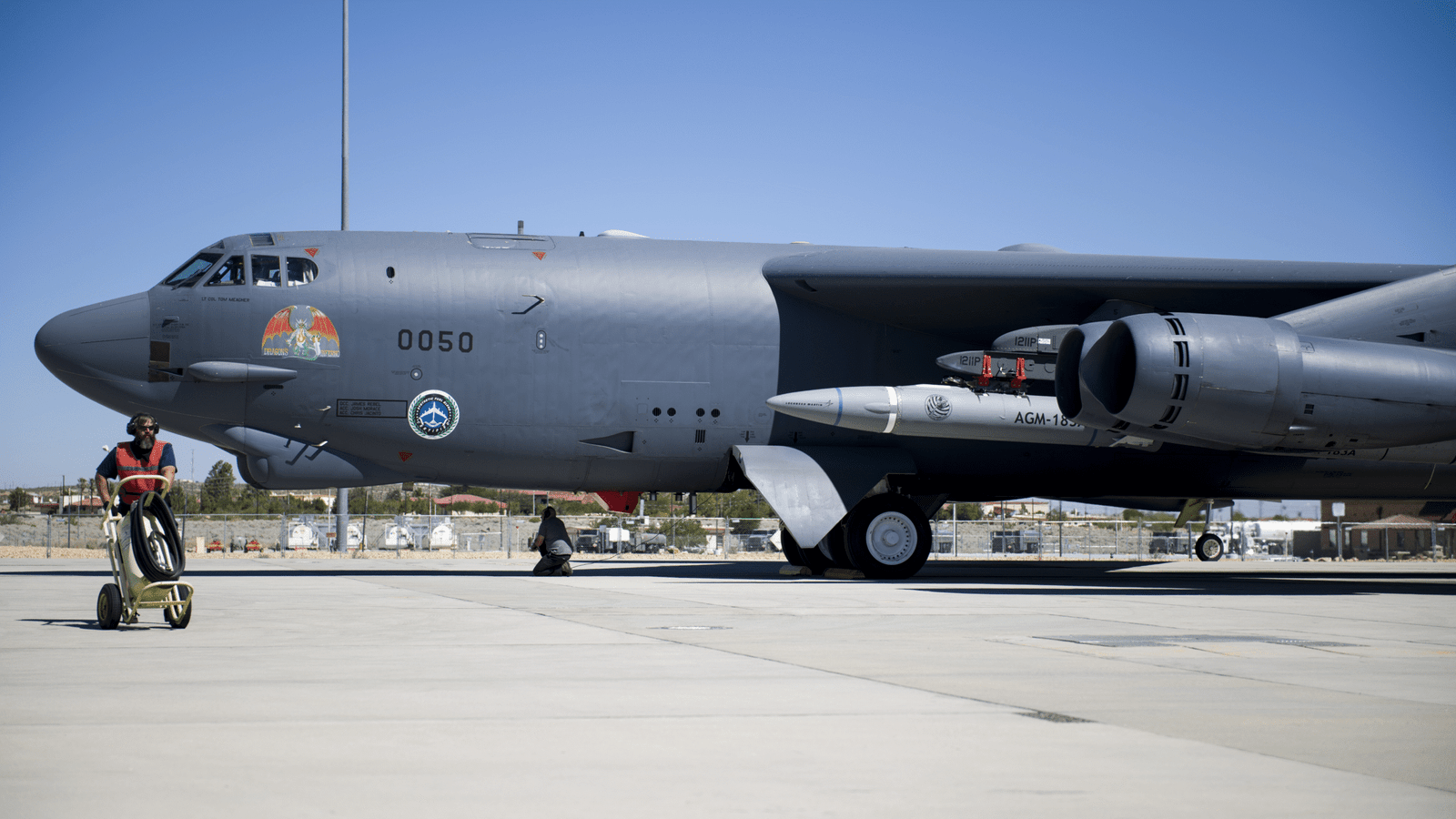

The program received support after the clandestine foreign use of hypersonics by the program was unveiled in 2018. Warning that it would act, the Pentagon did not spare any of the military branches. Lockheed Martin’s ARRW, which was developed from DARPA’s previous Tactical Boost Glide research, became the Air Force’s top priority in no time. It was originally intended to be launched from the B-52 Stratofortress, later supported by the B-1B Lancer and F-15E Strike Eagle. In an airborne range of approximately 1,000 miles, its booster aimed to launch a maneuverable glide body into the sky at scorching speeds, where it would bypass defense and destroy sensitive targets before an adversary had time to retaliate.

Unlike some of the hypersonics that were built as pure deterrents, ARRW was designed as a warfighting vehicle. The idea was straightforward but ambitious: a missile so fast that it would saturate the defense and so accurate that it would destroy critical targets in the first few minutes of the fight. To get there in a hurry, the program was treated under emergency prototyping authority, skipping some of the standard acquisition milestones to move at top speed.

But growing development came at unsustainable costs. ARRW faltered after its initial flight test in April 2021. Scores of missiles would not leave their carrier aircraft, some others would not launch, and others crashed during typical test phases. Lacking a fully tested demonstration plan, the program faltered from fiasco to fiasco. Specialists ultimately concluded that ARRW had to demonstrate that it was capable of delivering the combat credibility that it was meant to deliver.

Despite this, the Air Force continued for several years. Officials in 2023 indicated ARRW would not move forward past orders for prototypes. The funds would instead go to the Hypersonic Attack Cruise Missile (HACM), a scramjet project with greater endurance and uses. One of the early-run production lots of ARRW rounds was retained for purposes of test flight and information gathering; however, so the investment would not be wasted.

One of the few bright moments in the program was in early 2024. In February of that year, photos emerged of a B-52H over Andersen Air Force Base in Guam loaded with an AGM-183A live. It was not an engineering demonstration—it was an overt demonstration that the U.S. had an operational, if developmental, hypersonic-weapon capability in a forward theater. A couple of weeks later, on March 17th, a B-52H conducted a long-range mission and dropped an ARRW test article. The Air Force referred to it as an end-to-end test and produced valuable information, while Lockheed Martin referred to it as the final chapter of the program and the platform on which the next is established.

Whether the missile actually hit its target would be seen. More importantly, though, was the fact that the test validated ARRW’s mission as a matter of intent: long-range, high-rate-of-fire attack against strategic targets far away. It also pointed to Guam’s strategic value as a command point for Pacific-based bomber missions.

Even though the final result was a success, ARRW’s overall performance was spotty. Its majority of actual flights were tainted by failures of the booster, telemetry problems, or other malfunctions. For comparison, the Congressional Budget Office estimated each missile at between $14.9 million and $17.5 million-several orders higher than run-of-the-mill cruise missiles it would have been an expert’s tool even if it had been brought into service.

As ARRW winds down, the larger hypersonic contest has yet to abate. The U.S. subsequently turns to successor generations of design, such as HACM, with air-breathing propulsion for longer range and greater flexibility. Meanwhile, allied research programs are contemplating shared technologies and combined missile development, again suggesting this contest is hardly over.

Ultimately, ARRW has several test articles left. It is a lesson: early introduction of an untested weapon can sap confidence and capability both. The destiny of hypersonics will not be resolved exclusively through speed but through reliability, survivability, and combat utility. For America, the ARRW program is probably done, but the bigger competition is still in the making—and the challenge is not different: to build fast systems, yes, but responsive enough to rely on when necessary.