The Montana-class battleships are one of those intriguing “what if” tales of naval history—ambitious in conception, intimidating in size, and yet a testament to how rapidly the face of war can shift. Conceived during an era when battleships were the ultimate expression of naval might, the Montana-class was to be the largest and most fearsome fleet ships the U.S. Navy could muster. However, though there was careful planning and high hopes, no Montana ever went to sea. Its tale gives us a glimpse of how naval priorities evolved and how strategic decisions influence military history.

Before the start of World War II, battleships stood as the height of sea power. Each of the great navies competed to construct larger guns, heavier armor, and quicker hulls in an effort to outdo competitors. The Montana-class was America’s response to that competition—a logical extension of the fast, heavily armed Iowa-class battleships.

Other countries were building similar “super-battleships,” though few, if any, were ever finished. Authorized in the 1940 Two-Ocean Navy Act, the Montanas were designed as a class of five, meant to take battleship development to its limits.

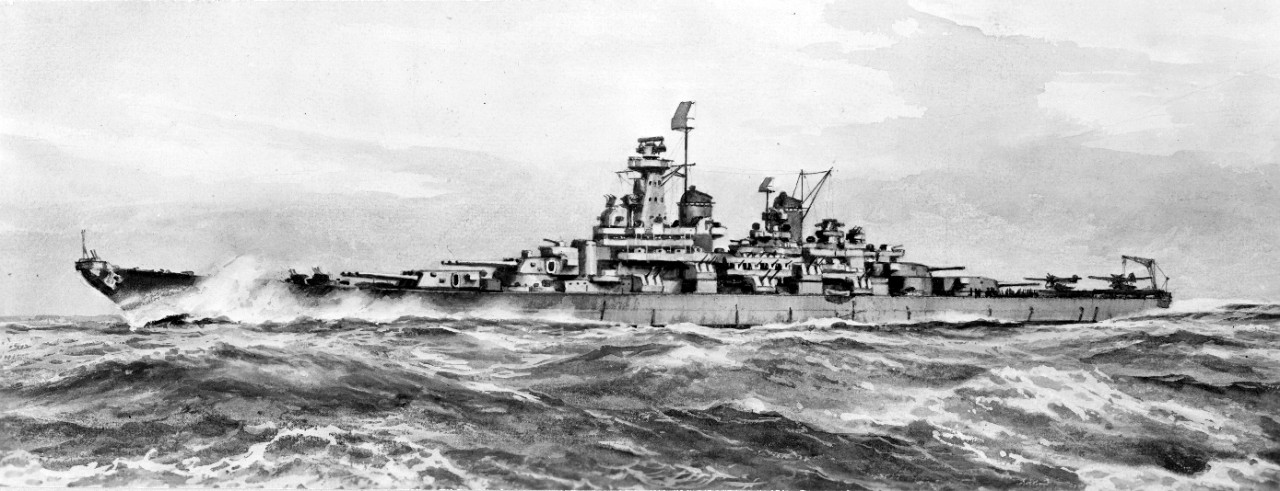

In terms of pure dimensions, these vessels were gigantic. Loaded to capacity, each Montana would have weighed in excess of 70,000 tons, beating the Iowas and being almost the size of Japan’s mythical Yamato-class. At 921 feet in length and 121 feet in width, they would have been so massive that Panama Canal locks had to be enlarged just to fit them.

Their guns were also formidable. Twelve 16-inch guns in four triple turrets provided them with three more main guns than the Iowas and about 25 percent more gunpower. They had twenty 5-inch dual-purpose secondary guns, more than past American battleships had, and dozens of smaller guns for anti-aircraft defense against the increasing threat from the air.

Armor was also a top priority. The main belt was 16.1 inches in width and sloped to provide more protection, and turret faces were armored to a depth of up to 18 inches. Critical areas such as ammunition magazines and engine rooms were protected with additional armor, and hull designs included torpedo and mine attack prevention features. Montanas were the first new U.S. battleships designed to accept direct hits from their own 16-inch guns.

All of this power had a price. The Montanas, compared to the Iowas, were less than a tenth of a knot slower, with eight boilers producing 172,000 horsepower for a maximum speed of 28 knots. They were constructed to last and fight in hard battles and not to scurry across the ocean at light speed—a testament to a more conventional, slug-it-out mentality.

But the Montana-class came at the wrong time in history. Aircraft carriers were becoming more important, and their capability to attack from miles away altered naval warfare. The Pearl Harbor attack in 1941 highlighted how even the huge battleships were susceptible to aerial attack.

By 1943, although the Montana-class was financed and sanctioned, the Navy decided to cancel them in a difficult choice. Funds were reallocated to aircraft carriers and other Iowa-class vessels—a strategic decision that put the U.S. at the forefront of the Pacific. If the Montanas were built, they could have been obsolete before they ever fired a shot.

Myths have long surrounded these ships. Others called them simply bigger Iowas with an additional turret, or imitations constructed only for the purpose of equalling the Yamato. They were actually a completely new design, with thicker armor and better secondary guns. Another fallacy is that they disregarded the Panama Canal size restrictions; although the locks at hand were too small, expansion was already in progress, and the real clearance problem was under the Brooklyn Bridge, close to the New York Navy Yard.

The Montana-class stands as the apogee and the nadir of the battleship era. Their cancellation was not a failure of vision or design—it was a realization that naval war had evolved. Prioritizing aircraft carriers, the U.S. Navy opted for a new reality in strategy. The Montanas are a tantalizing “what if,” a reminder that even the most powerful weapons can be made obsolete by shifts in technology and tactics.