The Convair B-36 Peacemaker was one of the most impressive airplanes ever built—a flying embodiment of Cold War determination, human genius, and brute mechanical might. Spanning the bridge between the piston engine bombers of World War II and the streamlined jet-powered planes that followed, the B-36 was the workhorse of America’s Strategic Air Command for more than a decade. It was not just a bomber, but a symbol of technological superiority and a testament to how much the industry had advanced in a matter of years.

The history of the B-36 originated in World War II, when American planners were anticipating the worst. If Britain fell and the United States lost its European base of operations, the armed forces would require a bomber with the range to penetrate deep into enemy lines straight from American shores. In 1942, the Army Air Corps made a truly remarkable request: a bomber with a range of 10,000 miles, an altitude of 45,000 feet, and a speed of more than 450 mph. Although those figures were subsequently modified, the task was truly monumental. Convair, at the time Consolidated Vultee, took on the challenge and set to work on one of the biggest and most complicated aircraft ever constructed.

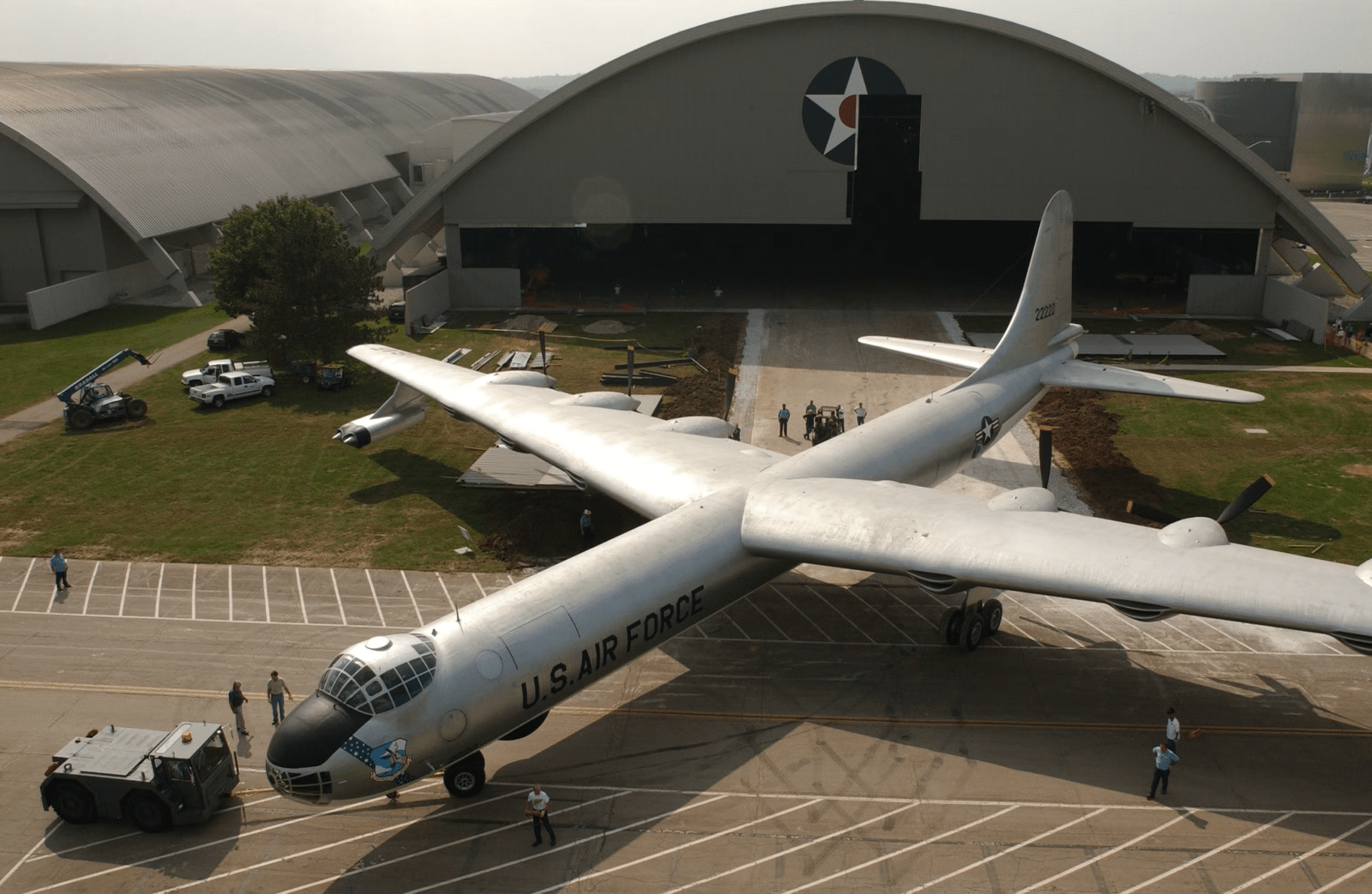

When the B-36 first materialized, it was nothing less than stunning. With a 230-foot wingspan and a fuselage over 160 feet in length, it was the largest mass-produced piston-engine aircraft ever constructed. Its wings were so large that crewmen could crawl inside them in flight to check on the engines. The power was provided by six Pratt & Whitney R-4360 radial engines in a rear-mounted “pusher” setup, where the propellers pushed the aircraft rather than pulling it. The later versions had four jet engines mounted beneath the wings, earning the nickname “six turnin’, four burnin’.” This combination provided the Peacemaker with the endurance of pistons and the additional thrust of jets when required most.

Within, the bomber was no less impressive. It could carry as much as 86,000 pounds of bombs—more than any plane ever—and early versions had 16 remote-controlled 20mm cannons for defense, although these were deleted as air combat tactics developed. In spite of its massive size, the B-36 could fly at altitudes that few fighter planes could and travel distances spanning continents.

Though the B-36 never dropped bombs during combat operations, it filled a critical function during the dawn of the Cold War. Entering service in 1949, it provided America with something no other nation could: the capability to transport nuclear warheads anywhere on the globe without requiring refueling. During an era when jet interceptors were still being developed, the Peacemaker could fly higher and farther than any potential adversary. Its presence alone was a deterrent, extending power and security in the midst of one of the most perilous times in recent history. Equipped to carry massive atomic and hydrogen bombs, the plane emerged as an important sign of America’s strength and preparedness. Missions had a tendency to last over 30 hours, a genuine challenge to the endurance of machine and crew.

One of the most intriguing chapters in the life of the Peacemaker was with the NB-36H, an experimental variant built to determine if a bomber could be powered by nuclear power. The working nuclear reactor was placed within a heavily shielded part of the aircraft, and the cockpit was lined with lead to safeguard the flight crew. Between 1955 and 1957, the NB-36H made scores of flights, experimenting with how radiation affected aircraft systems. While the reactor never powered the engines and the project ultimately came to a halt due to safety concerns, the experiment provided useful information that would shape future nuclear and aeronautical research.

Living on a B-36 was an existence in itself. A crew of about 15 operated the plane, which included pilots, navigators, engineers, and gunners. Missions could take longer than an entire day, so the Peacemaker had bunk beds, a galley, and even a small dining space within its pressurized sections. To those who flew it, the B-36 was more than a bomber—it was home in the air.

With a performance range of over 10,000 miles, a service altitude of about 50,000 feet, and a speed of close to 435 mph when the jets were operational, it was the pinnacle of long-distance strategic flight. But its size and strength came with persistent problems, from maintenance problems to the beating up of its intricate engines.

Its success notwithstanding, the Peacemaker’s dominion was not meant to last. With advances in jet technology, newer planes such as the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress started to beat it in virtually all aspects. The lower speed and inability to in-flight refuel meant the B-36 could not be as flexible, and supporting its huge engines became more and more problematic. By the late 1950s, it was evident that the future of strategic bombing lay with jet aircraft. Production of the B-36 ceased in 1954, and the final example left service in 1959, bringing the era of propeller-powered heavy bombers to a close.

Only a few examples of the B-36 survive today, contained in museums as silent witnesses to an important chapter of aviation history. Standing beneath one of these giants is a humbling experience—their size alone tells the story of a time when engineers dared to think bigger than ever before. The B-36 Peacemaker may have never fired a shot in anger, but it redefined what strategic airpower could be. It proved that the sky was not a limit but a frontier of possibility.

The Convair B-36 is still a testament to American aspiration and ingenuity, a span across worlds—the piston-engine bombers of the past and the jet-engine brutes of the future. Even today, decades after its heyday, it exists as a testament to how engineering imagination and international tension came together to produce one of the most remarkable planes ever to fly.