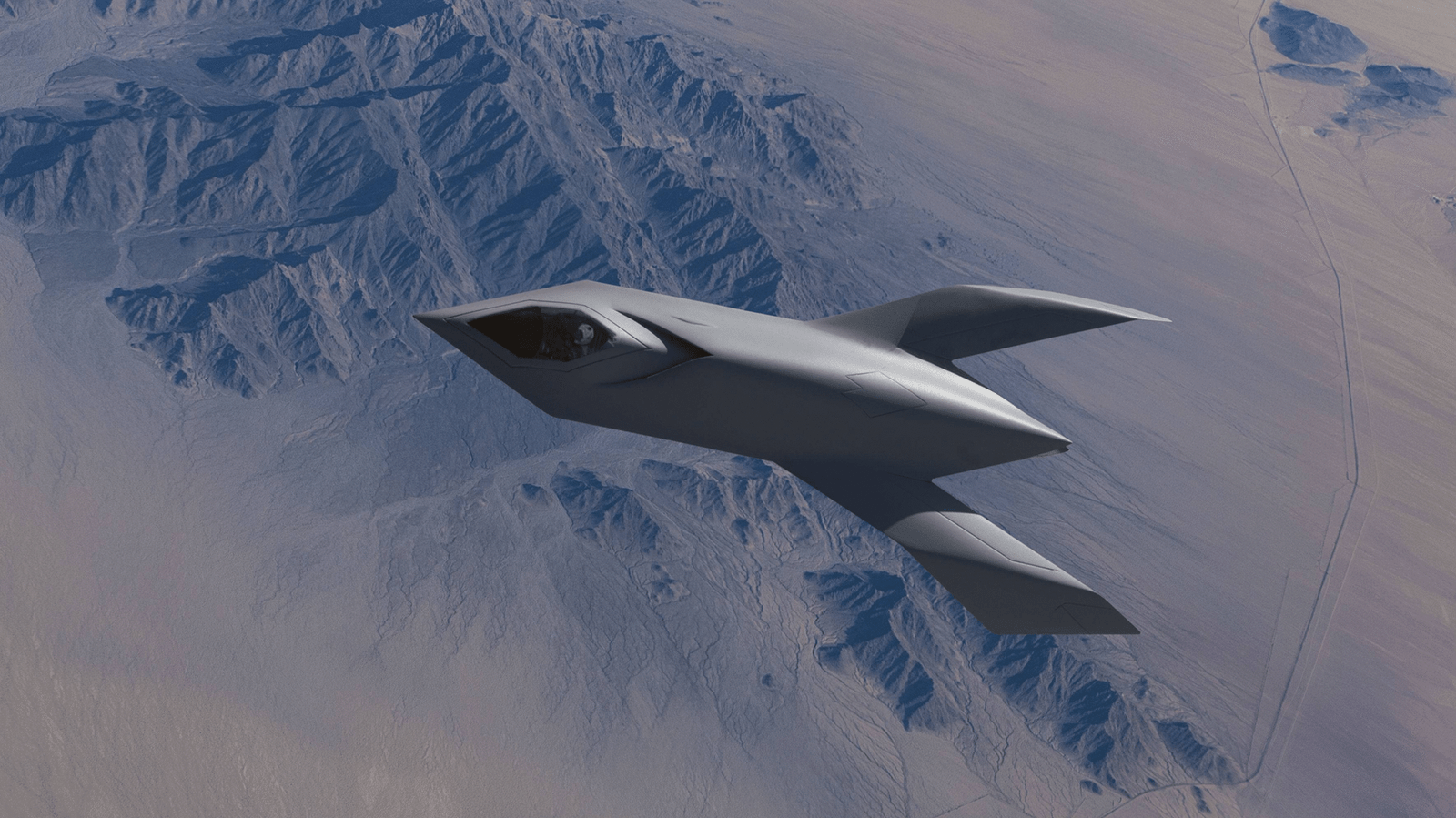

Stealth tech has always been a game of smoke and mirrors, but not many planes captured that combination of secrecy and bold innovation as well as the Boeing YF-118G Bird of Prey.

Conceived in the mid-1990s under the cloak of Area 51, this unique demonstrator not only moved the art of radar-evading design forward—it demonstrated that high-tech aircraft could be created fast and inexpensively without compromising imagination. Its tale is half engineering test, half strategic declaration, and wholly a lesson in inventive problem-solving.

The Bird of Prey arrived at the nadir of McDonnell Douglas’s fortunes. The company had lost the Air Force’s Advanced Tactical Fighter program to Lockheed and Northrop, which was then the dominant force in stealth. Rather than constructing another expensive, high-performance fighter, McDonnell Douglas’s Phantom Works group pursued a different course: design a small, inexpensive testbed to vault ahead in stealth technology.

The budget was tiny by space standards—a mere $67 million, less than the price of one new fighter—and the program squeezed it together through innovative use of off-the-shelf components, quick prototyping, and early computer-aided design programs that were in advance of their time.

It looked unlike anything else airborne. Its tailless, blended-wing appearance, with sharply raked wings and smooth contours, created a nearly alien look—an intentional reference to the Klingon warship from Star Trek. Every aspect of its design worked to support the stealth mission: a deeply recessed engine with an S-shaped inlet that concealed the compressor from radar, smooth control surfaces, and even custom paint patterns to distort its outline during daylight. The absence of vertical stabilizers was revolutionary during its time, but would be followed by more advanced drones and stealth bombers.

Under the exterior, the plane was a mosaic of borrowed parts: a Harrier seat, F/A-18 stick and throttle, A-4 rudder pedals, and, according to test pilot Doug Benjamin’s joke, “a Wal-Mart clock.” The Bird of Prey had no fly-by-wire system—its controls were all manual—so stability would have to be derived purely from airframe shaping. That it flew at all was a testament to prudent engineering.

The first flight occurred on September 11, 1996, piloted by Benjamin. During the following three years, the Bird of Prey flew 38 or 39 missions, gradually honing its handling and confirming its stealth capabilities. It was, by most standards of performance, disappointing—slow, capable of only about 20,000 feet—but performance was not its purpose. The objective was to demonstrate that advanced stealth technologies and quick-building techniques could be flight-tested at a fraction of the normal expense. On that front, it was a success.

The Bird of Prey’s silent legacy is vast. Its influence can be followed on subsequent Boeing projects such as the X-45A Unmanned Combat Air Vehicle, stealth shaping and construction methods utilized in the F-22 Raptor, F-35 Lightning II, and even the future B-21 Raider.

Behind the effort were individuals such as Alan Wiechman, a Skunk Works veteran from Lockheed who lent considerable stealth experience to Phantom Works, and Doug “Benj” Benjamin, whose flights ironed out the demonstrator’s idiosyncrasies and gave life to its design.

Now, the Bird of Prey remains suspended at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force, dramatically hanging over an F-22. People can’t get into the cockpit, and in one sense, that’s appropriate—the secrets of the plane are literally beyond their grasp. It’s a reminder that some of the greatest advances in military aviation occur far from the glare of the media spotlight.

To engineers, pilots, and strategists, the Bird of Prey is proof positive that innovation does not always involve billion-dollar budgets or huge production runs. Sometimes, the most influential players are the ones that silently fly by, revolutionize the game, and then retreat into the background.

More related images you may be interested in: