Stealth always had a kind of genius, secrecy, and outrageousness to it, and few aircraft capture all three elements of that formula as thoroughly as the Boeing YF-118G Bird of Prey. This incredible plane, crafted in the mid-1990s under the watchful eye of Area 51, was not merely an engineering experiment—it was a statement about what can be achieved when imagination is placed in the crucible of constraint.

It showed that advanced airplanes could be constructed quickly, inexpensively, and on a shoestring budget without compromising innovative design or technical creativity. It is both a lesson in how to innovate and an insider pronouncement of strategic acumen.

McDonnell Douglas, in the meantime, was fighting to let go of the Advanced Tactical Fighter program to stealth industry leaders. Rather than trying to match them by creating a costly, high-tech fighter, McDonnell Douglas’ Phantom Works unit did something else. They constructed a small, low-cost testbed to push the limits of radar-evading technology.

The Bird of Prey was built on a shoestring by aerospace standards—a combined budget of only $67 million, less than the cost of one new fighter aircraft. The team extracted every penny out of it through sheer creativity on the utilization of off-the-shelf components, rapid prototyping, and state-of-the-art early computer-aided design facilities that were decades ahead of their time. The resulting aircraft was unlike anything seen in the skies.

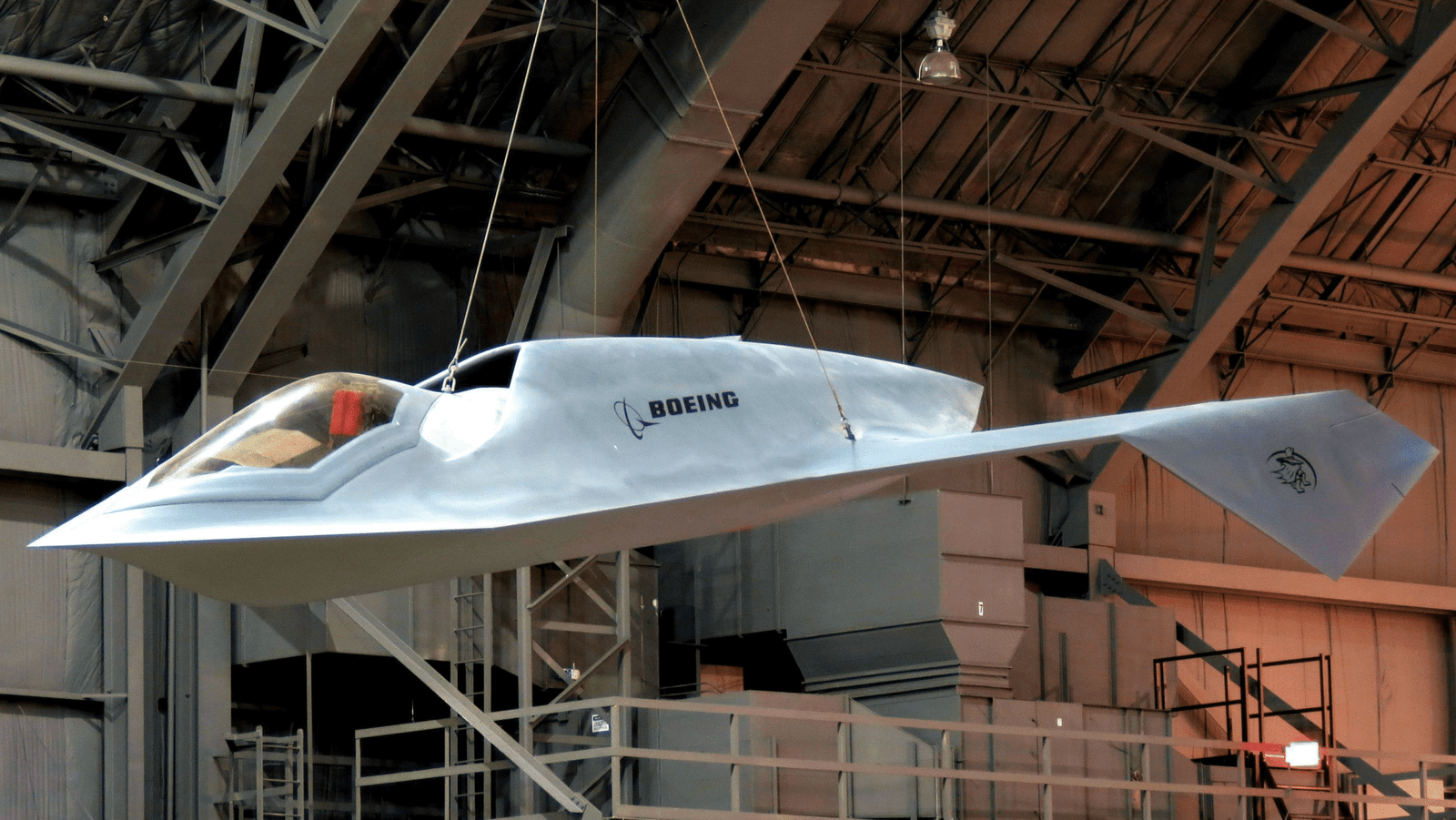

Tailless, mixed-wing design with sharply swept wings and smooth lines produced a close to alien appearance, specifically inviting a sense of fantasy, Klingon ships from the Star Trek universe. Every aspect of its design aimed at the stealth mission: an S-shaped intake to cloak the compressor from radar, smooth panels to prevent reflections, and camouflage-style paints to disrupt its profile in sunlight. Its lack of vertical stabilizers was a breakthrough for the period, a design feature that would return on stealth bombers and UAVs.

On the inside, the Bird of Prey was a Frankenstein’s monster of components stolen from other airframes: Harrier ejection seat, F/A-18 stick and throttle, A-4 rudder pedals, and, as test pilot Doug Benjamin deadpanned with witlessness that is to be admired, “a Wal-Mart clock.” Having no fly-by-wire, the airplane’s stability lay entirely in shape and design. That it flew at all was a testament to good design and imagination.

The Bird of Prey flew for the first time on September 11, 1996, in Benjamin’s command. Over the next three years, it flew around 38 times, honing its handling and proving its stealth feature. By conventional performance criteria, it was humbly low-keyed—slow and limited to around 20,000 feet—but that was not the point. Its purpose was to demonstrate that it was feasible to flight-test new stealth technology and rapid-build techniques at a part of the normal cost. In that regard, it succeeded by a landslide.

Bird of Prey’s existence went unnoticed in the annals of American aviation. Its clandestine character, materials, and manufacturing processes were encapsulated in Boeing’s X-45A unmanned combat air vehicle, F-22 Raptor, the F-35 Lightning II, and even the coming B-21 Raider.

Names like Alan Wiechman, a Skunk Works veteran and decades-long expert in stealth, and the likes of Doug Benjamin, who flew the plane to flight and solved its unique challenges, lay behind the aircraft’s success.

Now the Bird of Prey hangs over an F-22 at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force, out of viewers’ sight and out of reach. Perhaps that is fitting, given what it is. It’s a reminder that some of aviation’s most important milestones take place behind closed doors, out of sight.

To strategists, pilots, and designers, the Bird of Prey is a reminder that genuine innovation is not a matter of billion-unit production runs or appropriations. The most successful breakthroughs are often the quiet ones that happen quietly, rewrite the rules, and then slip away into the background.