Stealth flying has always occupied that odd realm between science and magic, but few planes captured that blend of secrecy and audacious design better than the Boeing YF-118G Bird of Prey. Born in the mid-1990s and tested in the shadow of Area 51, this peculiar little airplane advanced stealth thinking while demonstrating that futuristic planes need not cost an arm and a leg or decades to build.

Its history is one of experimental engineering, quiet declaration of purpose, and, most of all, an example of what happens when imagination leads innovation.

The Bird of Prey came during a nadir for McDonnell Douglas, which was still smarting over losing the Air Force’s Advanced Tactical Fighter contract to Lockheed and Northrop. Rather than invest in yet another expensive fighter design, its Phantom Works division took a different tack: create a small, inexpensive test vehicle that could leapfrog the competition in stealth technology.

The budget was amazingly bare—only $67 million, fewer than the cost of a single production aircraft. Engineers made every dollar go as far as possible by employing commercial components, rapid prototyping, and cutting-edge computer-aided design software that was precognitive.

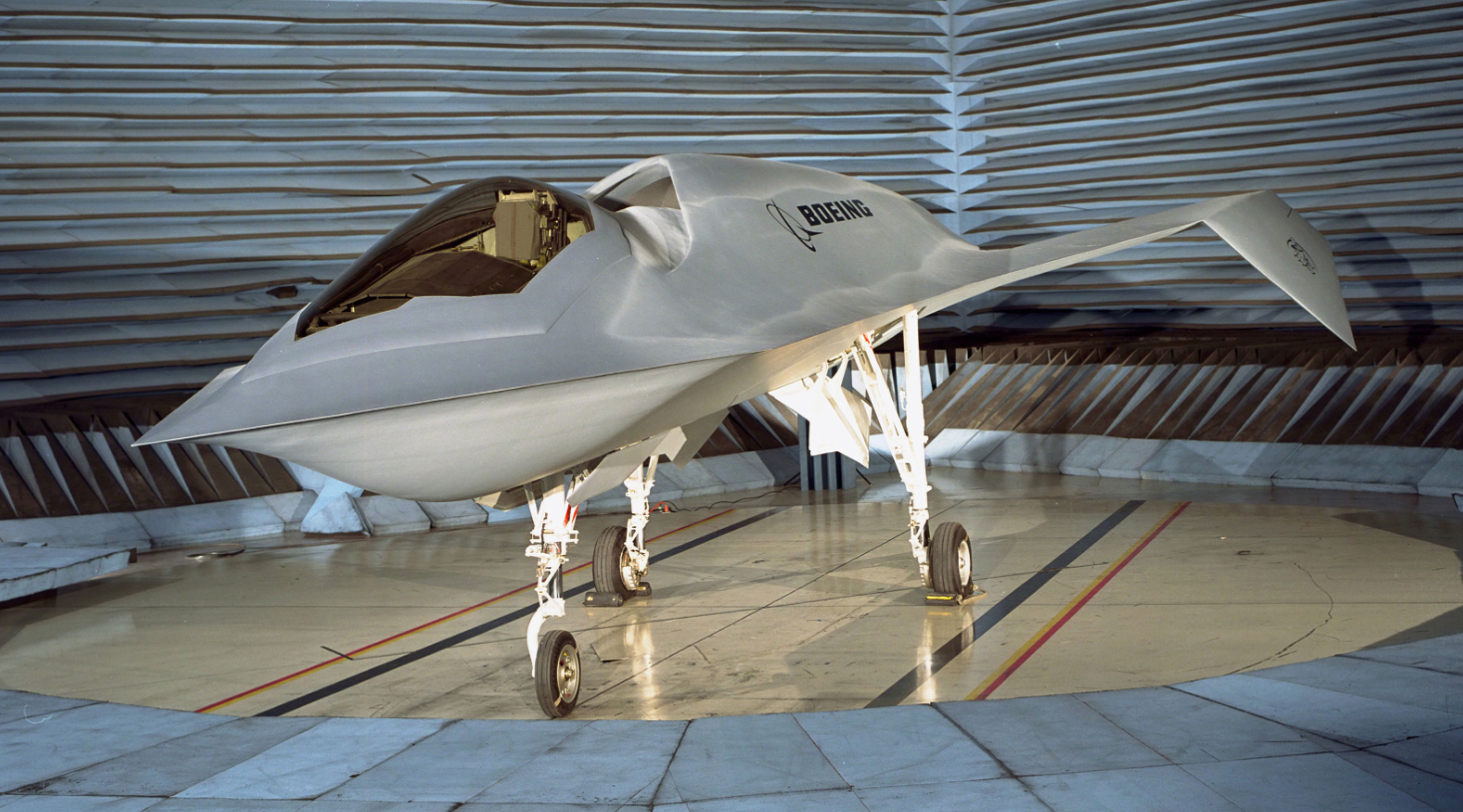

The outcome was an aircraft that was unlike anything else in the air. Its tailless, blended wing body with angulated and sweeping lines looked more out of science fiction than anything else, borrowing ideas even from Star Trek’s Klingon warship.

Each bend had a purpose: one buried engine deep with an S-bent inlet to conceal radar reflections, sleek control surfaces, and even paint formulated to distort its outline in the daylight. The absence of vertical stabilizers was revolutionary for the time, but eventually became prevalent on stealth drones and bombers.

Underneath that futuristic veneer, however, was a mishmash of pilfered pieces—a Harrier ejection seat, throttle and stick from an F/A-18, rudder pedals from an A-4, and, as pilot Doug Benjamin used to joke, even “a Wal-Mart clock.” Stability without fly-by-wire controls had to result from its design alone. The very fact that it did fly at all was a testament to how meticulously the team had configured it.

Its maiden flight was on September 11, 1996, with Benjamin pilot. In the next three years, it made nearly 40 flights, each one reinforcing confidence in its handling and stealth characteristics. By performance criteria, it was underwhelming—slow, with a ceiling at about 20,000 feet—but that was never the intention. What was important was demonstrating how innovative stealth concepts could be flight-tested in the air rapidly and inexpensively, and on that point, the Bird of Prey succeeded.

Although it never fought or was produced in quantity, its fingerprints are omnipresent. Boeing’s subsequent X-45A unmanned combat vehicle, as well as stealth methods employed in the F-22, F-35, and even the future B-21 bomber, all have their roots in the silent lessons of this small demonstrator.

Behind the project stood individuals such as Alan Wiechman, a Lockheed Skunk Works veteran, and Doug “Benj” Benjamin, the test pilot who coaxed the strange plane through its motions. Their efforts served to establish that a daring concept could be made a flying fact without the burden of billion-dollar programs.

Now, the Bird of Prey sits suspended at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force, looming over an F-22. Its visitors can’t get into its cockpit, and in a sense, that’s appropriate. Its real secrets lie just beyond reach, a reminder that some of aviation’s greatest leaps occur out of sight, out of the spotlight and headlines.

To observers, Bird of Prey still serves as evidence that oftentimes the most powerful planes aren’t necessarily the loudest nor the fastest, but rather those that quietly reauthenticate the standards before receding once again into silence.