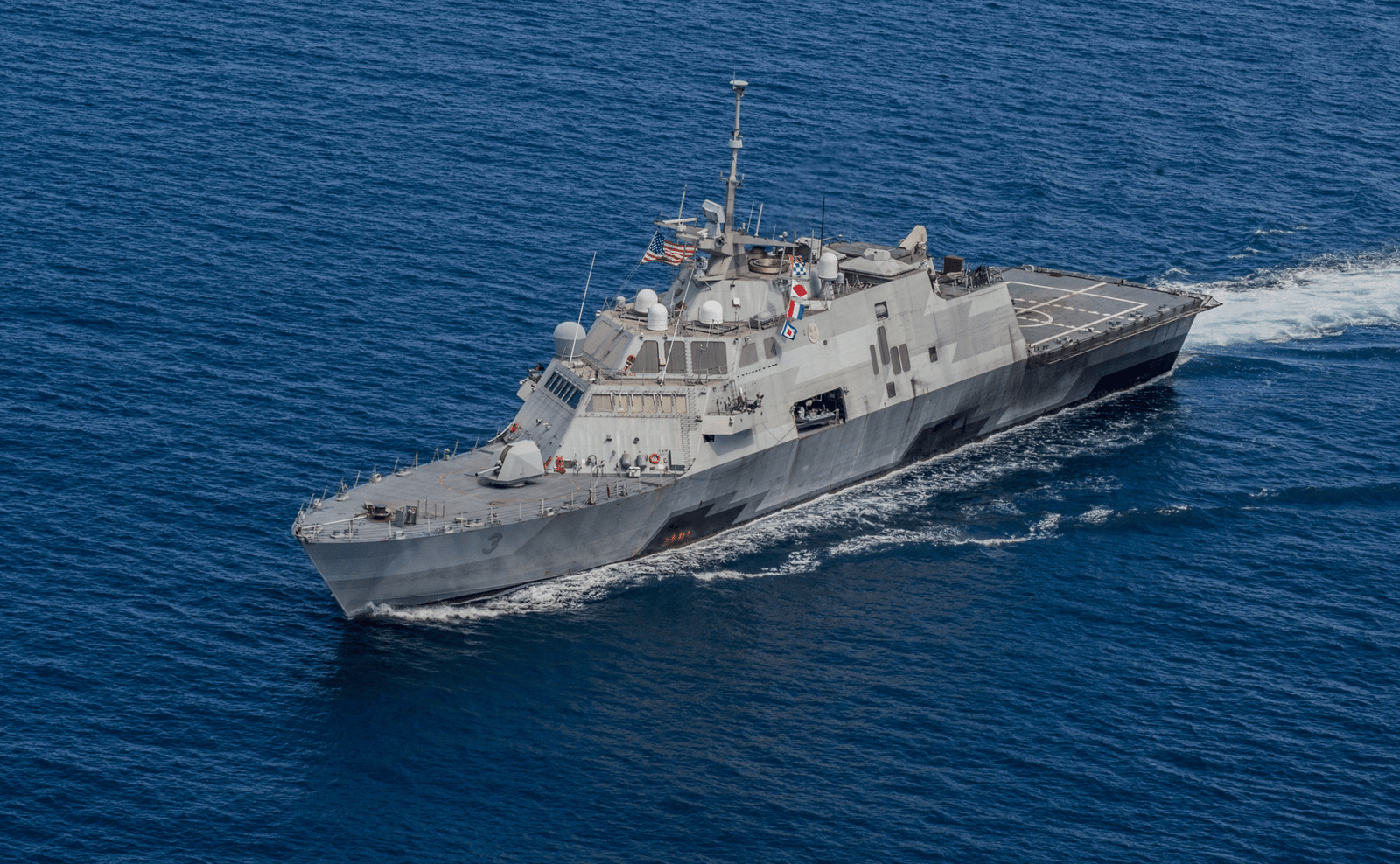

The Littoral Combat Ship was marketed as an American Navy game-changer — a fast, multi-mission vessel that would confront mines, subs, and other perils close to shore. On paper, it would bring new flexibility to naval warfare. In reality, the LCS was one of the most contentious and debated programs in modern naval warfare history, a costly program that was plagued by delays, technical problems, and failed promises.

In the wake of the Cold War, the Navy needed to redefine its priorities. The massive battleships and carriers were no longer the best solutions for the new coastal warfare configuration. What was needed was a leaner, meaner vessel that would rapidly shift missions but have fewer sailors. The LCS was meant to fill the gap — an adaptive, multi-mission ship that would fill whatever was required.

The theory was sound, but the practice was far more nuanced. Instead of selecting one design, the Navy divided its hunt into two competing designs: Lockheed Martin’s Freedom-class conventional steel-hulled design and General Dynamics/Austal’s aluminum Independence-class trimaran. While this approach was intended to stimulate ingenuity and keep shipyards active, it brought more layers of complexity, confusion, and costs that multiplied year by year.

Their calling card was to be LCS’s mission packages, but they were a headache. Expensive to build and often breaking down, the packages were barely so much as promised. But the ships themselves were not immune to mechanical issues — engine breakdowns, leaks, and other breakdowns that sometimes forced them to sail back to port ahead of schedule.

Little squads were attempting to keep up with the maintenance requirements, so contractors were frequently hired, only adding to the more and making logistics even more involved.

Critics were not kind. Many analysts and watchdog groups declared LCS a failure, citing that the ships spent more time in port than they did sailing at sea. Their comparatively weak guns made them vulnerable if confronted with a determined enemy, and the repeated program delays raised skepticism about the value of the program as a whole.

Politics assisted in maintaining the program as well. Legislators lobbied to continue it to maintain jobs in their districts, and defense-contracting companies lobbied to maintain contracts. As questioning of the value of the program to the Navy grew, these external pressures maintained it, and the 33 ships that cost almost $100 billion were constructed.

Over time, the Navy attempted to improve the LCS’s capabilities, such as adding more advanced weaponry in the form of the Naval Strike Missile and using unmanned drones as a surveillance option. Some officials still praised the ships as fast and able to operate on intelligence-gathering missions, but reforms could not wipe away the program’s tarnished history.

With the commissioning of the last Independence-class ship, the USS Pierre, the Navy is bringing down the curtain on this act. Although the LCS never fully realized its initial promise, it did push naval design and operational innovation down alternative paths, providing lessons that will be felt in future programs.

The LCS soap opera is a cautionary history of ambitious ideas locked in battle with technical challenges and political imperatives. It instructs us on how defense programs as recalcitrant as possible are driven by the confluence of interests — military, political, and industrial — in spite of all warning lights glowing red. The LCS has lessons that will guide future programs to more realistic and sustainable shores.

In the end, the Littoral Combat Ship will not be regarded as a success of naval engineering, but as an admonitory instance of the exasperating and troublesome nature of military innovation.