The Convair B-36 Peacemaker was one of the most brazen and astonishing aircraft ever produced. It was huge, complicated, and conceived in the throes of wartime necessity—a flying testament to the raw fervor of the early Cold War. Its roots lay in the last years of World War II, when the American strategists were concerned that Great Britain would be overrun and the U.S. would lose its bases in the forefront for bombing sorties.

To keep striking power alive, the Army Air Forces called for a bomber that would have unprecedented requirements: to fly 10,000 miles, penetrate to over 40,000 feet, and be able to carry sufficient bombs to attack far-off objectives across continents.

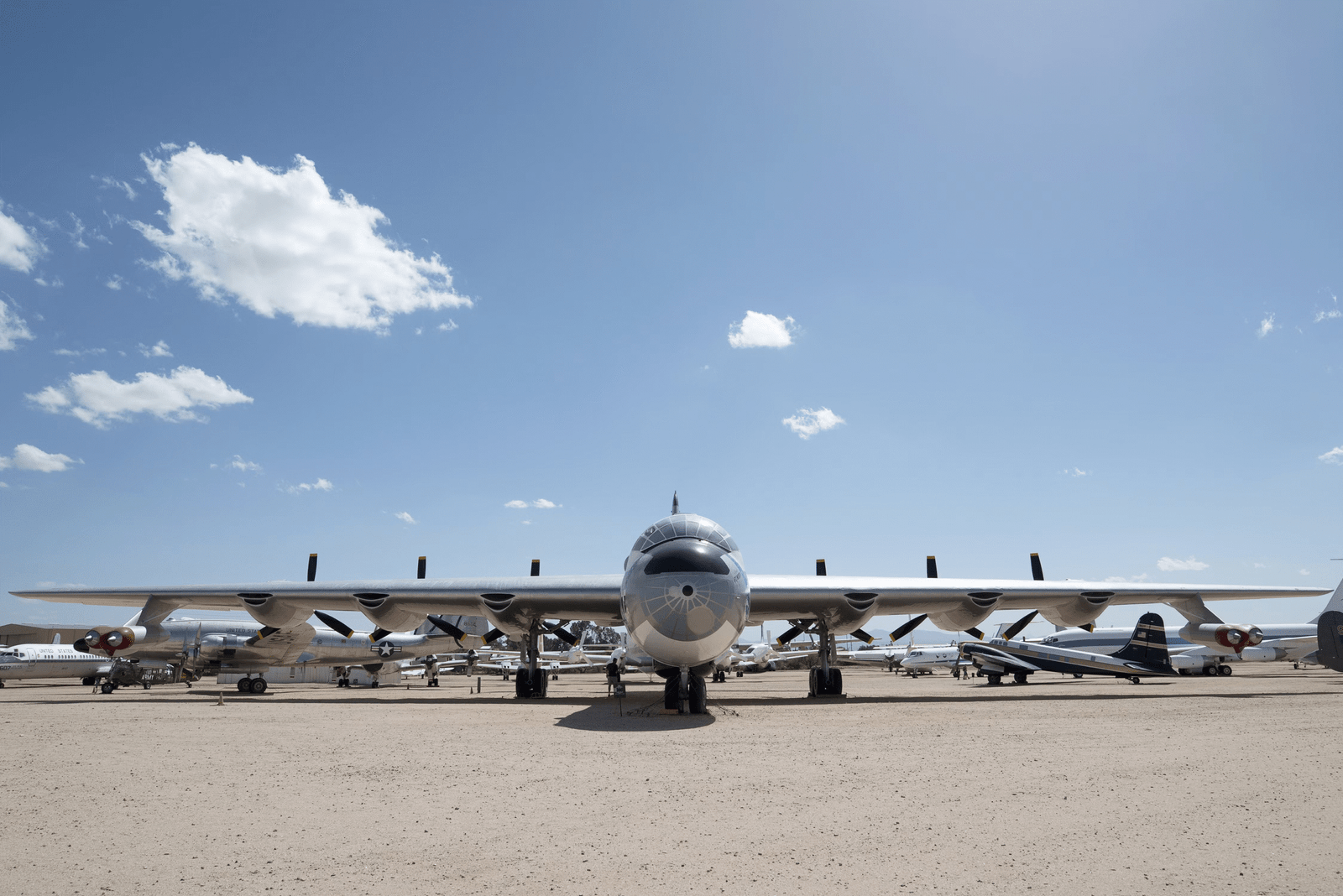

Convair, which was previously Consolidated Vultee, secured the contract in 1941 after defeating Boeing. Constructing the B-36 was anything but straightforward. The requirements of the job strained available technology to the breaking point, causing redesign after redesign and delay after delay. Its ultimate design was huge, with a 230-foot wingspan—the biggest ever placed on a combat plane. They were so dense that engineers actually constructed crawl spaces within them, which enabled personnel to maintain the engines during flight, a fact that still amazes aviation buffs today.

At the monster’s core were its engines. The initial models depended on six Pratt & Whitney R-4360 Wasp Major radial engines in a unique “pusher” layout, with propellers behind the wings. Subsequent variants used four General Electric J47 turbojet engines under the wings. That odd combination created the now-famous terminology for the plane: “six turning, four burning.”

The outcome was an airplane that flew at a cruising speed of about 200 miles per hour and could fly in excess of 400 miles per hour at higher altitudes. Slow for today’s jets, this was impressive for an aircraft of its size. The final production variant, the B-36J, could fly up to almost 40,000 feet while carrying a maximum takeoff weight of 410,000 pounds. Even years after the fact, those statistics are impressive.

When the B-36 entered production in 1948, the Cold War was in its formative stages, and the Strategic Air Command, created as part of the new National Defense Establishment, needed a long-range nuclear defense deterrent. The Peacemaker was designed for the purpose. It could carry an 86,000-pound bomb load—more than four times as much as the legendary B-29—America’s heaviest atomic and thermonuclear weapons to targets across an ocean.

Others were modified for reconnaissance purposes, and test models such as the NB-36H were even equipped with a small nuclear reactor to test atomic-powered flight. Early in its life, the bomber was essentially immune to enemy defenses due to its altitude and range.

But life on the B-36 was anything but glamorous. Crews of 15 to 22 men rode out flights exceeding 40 hours, frequently in cramped, semipressurized space well above the ground. The engines were finicky, maintenance was rigorous, and endless vigilance was needed to maintain flight. Early models were heavily armed with as many as sixteen remotely controlled 20mm cannons, although these were later cut back as jet fighters became the greater threat.

All its potency aside, the Peacemaker never discharged a single shot in combat. Its utility was symbolic as well as strategic—a tangible reminder to foes of America’s nuclear power. Critics pejoratively dubbed it the “Billion Dollar Boondoggle,” asking whether its price had been worth paying. Nevertheless, for over a decade, it was the core of U.S. nuclear deterrence, filling the gap between the piston-engined bombers of World War II and the jet-powered B-52 Stratofortress that would eventually supplant it.

By the mid-1950s, developments in jet technology rendered the B-36 increasingly obsolete. Its speed and maintenance needs curbed its long-term utility, and production stopped in 1954 after 384 had been constructed. The final flight was on April 30, 1959, when a B-36 was presented to the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force, where it is still preserved.

The impact of the B-36 is staggering. It pushed the limits of engineering, shaped bomber design for decades, and took a pivotal place in Cold War strategy without ever fighting. Its enormity, ten engines, and distinctive shape made it a sight to remember—a behemoth both feared and respected. Only fewer than ten remain today in museums, quiet sentinels of an era when the fate of world power rested on wings nearly as broad as a football field.