At the beginning of the 21st century, the American Army embarked on a bold endeavor: reinventing the tank. At the forefront was the XM1202 Mounted Combat System, a vehicle conceived to replace the M1 Abrams with an amalgamation of speed, firepower, and cutting-edge functionality. But the XM1202 was not merely a new tank—it was the center of the gargantuan Future Combat Systems (FCS) program, a grandiose effort to reconstitute the Army as a lighter, more agile, and more networked combat force.

The FCS program, initiated in 1999 by Army Chief of Staff General Eric Shinseki, had in mind developing a family of vehicles on a single basic platform. The theory was straightforward: modular design would simplify maintenance, minimize logistical suffering, and offer quick deployment-even on C-130s by air.

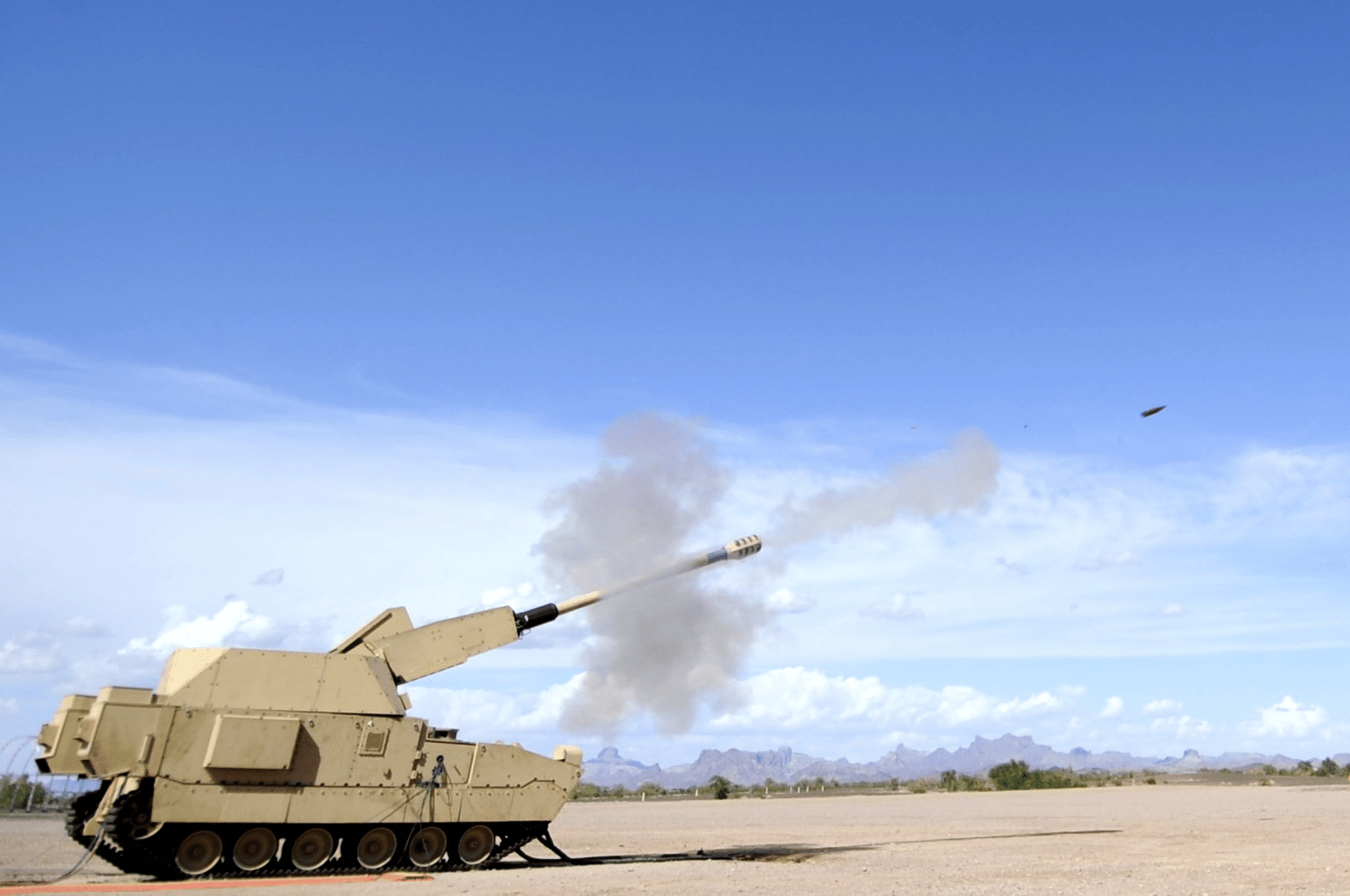

The XM1202 was merely one of eight manned vehicles planned, every vehicle with a particular mission but with common components and homogeneous digital architecture. It was its adoption of technology, which at the time seemed to be extraterrestrial, that made the XM1202 distinctive. Its XM360 lightweight 120mm gun had the ability to fire standard shells and guided missiles.

The tank even carried the XM1111 Mid-Range Munition, a gun developed to strike targets out of sight of the crew—a technology that might have revolutionized tank warfare. Automation was involved as well: an autoloader cut the number of crewmen to a driver and commander, transferring work once done by hand to machines.

Electronics were just as bold. Sophisticated infrared sensors and networked battlefields offered levels of situational awareness unmatched before. Active protection systems such as Raytheon’s Quick Kill would annihilate incoming attacks, negating the XM1202’s thinner armor. It weighed approximately 18 to 24 tons, much less than the Abrams, and thus easier to move but with concerns over how well it could withstand direct hits.

But these advances were the tank’s vulnerability. Shedding weight without sacrificing firepower and armor was much harder to do than engineers had hoped. Much of the supporting technology was still experimental. Merging it into a single functioning vehicle presented technical challenges that were practically insurmountable.

Paralleling these developments was the transformation of the character of the battlefield itself. Iraq and Afghanistan added up to decades of combat that exposed the lethal effects of IEDs, and armored vehicles were needed to counter them. Fast, lightweight tanks like the XM1202 no longer appeared so viable at that stage, and there was a demand for vehicles like MRAPs, which provided significantly higher survivability in counterinsurgency warfare.

Money and bureaucracy only exacerbated the problem. The FCS program gained a reputation for runaway expense and paltry returns. It was canceled in 2009, having devoured more than $18 billion and never producing a single deployable vehicle.

The XM1202, whose questionable battlefield worth and risk-high profile made it one of the first places to cut costs, only further clouded the issue. Contract coordination by contractors such as Boeing, General Dynamics, and BAE Systems made it all the more so.

When Defense Secretary Robert Gates shut the door, the Army retreated to its traditional way: renovating current platforms like the M1 Abrams and Bradley Fighting Vehicle instead of experimenting with untested ideas. It was a choice between what worked today and what may work in the far-off future.

Yet the XM1202 was not completely lost. A majority of the technology that was developed—networked communications, active protection systems, light weight materials—was diverted to other programs. And most significantly, probably, the XM1202 and the FCS program learned the hard way: innovation is necessary, but it has to be tempered by practical reality. That lesson still influences the Army’s thinking about armored vehicle design today.