In a world where technology is remaking the rules of war, few weapons embody that change like the Lockheed Martin Mako hypersonic missile. It’s not only a shiny new gadget—it’s a glimpse of what combat in the future will look like, where speed, accuracy, and survivability aren’t niceties but the building blocks of modern warfare.

From its inception, the Mako was never intended to be another run-of-the-mill missile. It was meant to be a missile that could counter quickly changing threats with little or no warning. Lockheed Martin describes it as a system intended to “strike time-sensitive targets when every second matters.” That’s not an advertising tagline—it’s the weapon’s design ethos. Able to fly at hypersonic velocities yet still maneuver mid-flight, the Mako is able to pierce through layered defense, change course, and strike its target before an opponent can even react.

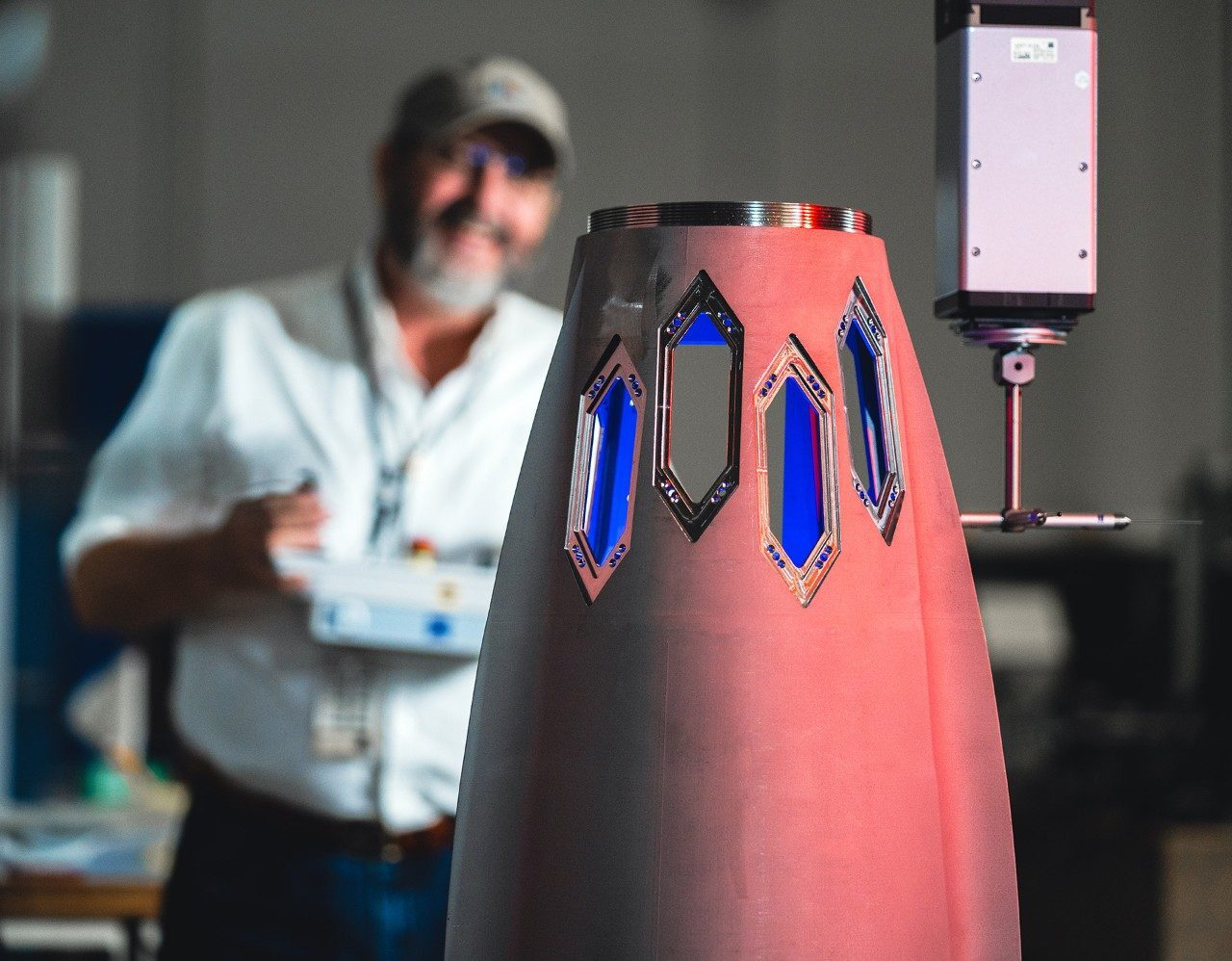

What distinguishes the Mako most isn’t what it does—it’s how it was built. A heavy 1,300 pounds and 13 feet long, it’s diminutive enough to fit in the secret weapons bays of stealth fighter aircraft like the F-35 and F-22. It’s not an accident that it’s this size. It’s precisely small enough to enable aircraft to stay invisible to radar with a missile powerful enough to destroy high-priority targets far behind enemy lines.

Powered by a solid-fuel rocket engine, the Mako flies beyond Mach 5. Speed alone isn’t what kills it—it’s maneuverability at these speeds that makes it virtually impossible to intercept. It can turn in mid-air, shedding even the most effective tracking systems and making capture a virtual impossibility.

Versatility takes center stage in the Mako’s design. It can attack fixed installations, mobile air-defense systems, or even warships. It’s also highly adaptable across platforms. The missile has already been qualified on several different aircraft—F-35, F-22, F/A-18, F-15, F-16, and the P-8 anti-submarine warfare aircraft. If an airplane can lug standard 30-inch lugs, then it can lug a Mako. Lockheed Martin is even creating versions that may be fired from ships and subs, extending beyond the air into the sea.

What really distinguishes the Mako from previous designs is the method of construction. The entire system was designed in a fully digital environment. Everything, from the airframe to the guidance electronics, was developed, tested, and refined in computer simulations prior to building a single actual component. This digital-first architecture enables the engineers to merely update components, swap out sensors, or modify warhead configuration according to mission needs. Combined with 3D printing and advanced manufacturing capabilities, this process minimizes production time and cost—making the Mako both highly capable and affordable.

That cost-effectiveness matters. In the words of Lockheed Martin’s Rick Loy, the Mako was conceived to balance power and pragmatism. That makes it appealing not only to U.S. forces but also to allied military forces looking to modernize without breaking the budget. With its compatibility with much of the aircraft already being operated by NATO and AUKUS allies, it can be quickly deployed in large numbers, augmenting joint defense capabilities without requiring new infrastructure.

Strategically, the impact is staggering. At a time when adversaries rely on distant defenses and advanced missile shields to close the door, the Mako reverses the situation. It gives stealth aircraft the ability to strike deep and fast, targeting mobile launchers or radar sites before they can strike back. That sort of speed and precision puts the enemy response time at seconds—usually too brief to defend themselves. Designing a weapon that can maintain control at five times the speed of sound is no simple accomplishment. But Lockheed Martin’s creation of the Mako proves otherwise. The missile proves that America is not just catching up with the hypersonic competition—it’s in the lead.

There’s also a greater context to be considered. Lockheed Martin intends to build and maintain the Mako in partnership with allied nations, forging industrial and defense relationships. It’s an example of how collaboration and innovation can go forward hand-in-hand, ensuring allies benefit through mutual knowledge and technology.

While other nations can boast hypersonic hype, the Mako does so modestly. It’s not about hype and headlines—but capability, precision, and purpose. Combining speed, smart engineering, and multi-platform versatility, it is a true step forward in contemporary weapon design.

As threats around the globe grow more complex and untrustworthy, the Mako is more than just a new weapon—it’s a preview of things to come. Uniting innovation, adaptability, and vision, it is the future of deterrence: one in which the U.S. and its allies don’t just respond to threats—they stay far ahead of them.