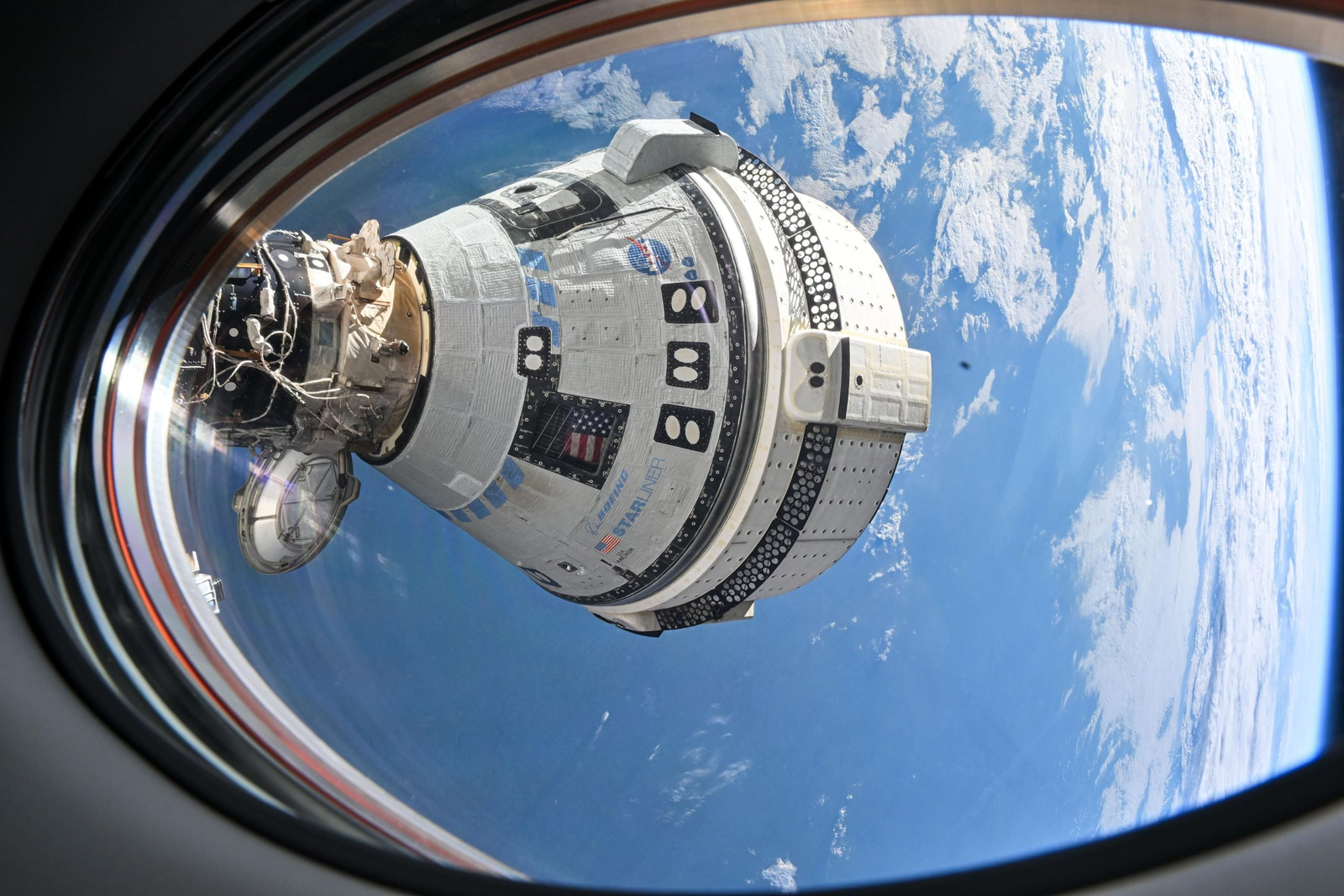

When Boeing’s Starliner finally launched from Cape Canaveral with NASA astronauts Butch Wilmore and Sunita Williams aboard, the flight was a slow-motion triumph. After years of delay and misstep, the flight was to be straightforward: an eight-day trip to the International Space Station to prove that Starliner would be a viable backup to SpaceX’s Crew Dragon. But not so. The mission was instead a tutorial on how mission plans adapt when real life — and the harsh realities of space — intrude.

The launch was favorable. Two unmanned test flights had already taken some of the issues for a spin, and now, for the first time in history, humans were riding along. Navy test pilots Williams and Wilmore understood that space flight never comes with a script.

Their gut was correct. When Starliner was closing in on the station, ground controllers picked up helium leaks and learned that five of the spacecraft’s reaction control thrusters were not functioning as they should. Those are small but important thrusters: for vehicle alignment, executing precise orbital maneuvers, and aiding in a safe deorbit burn. The mission was now more than a routine checkride; it was a bona fide live troubleshooting simulation.

Technicians and engineers dove into diagnostics. In White Sands Test Facility, crews tried to reproduce the failures with the aim of finding root causes. One of the top theories was heat causing Teflon seals in thruster hardware to contract and expand fuel flow; occasionally, the thrusters returned, occasionally they didn’t. Even half a step wasn’t enough to rebuild full confidence. Too many secrets, said Steve Stich, manager of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program, meant not jumping to a solution.

Knowing that, the problem was a matter of operations and ethics, not technology: how do you manage a short-term mission facing an irresolvable safety issue? The choices were stark. Land the astronauts on Starliner as planned and take the residual risk, or leave them on board and recover them later on another vehicle.

Had NASA brought them back on Starliner, that would have been a show of confidence in the system; stranding them on the ISS and awaiting the next flight kept conservatism at the forefront. Only after a much drawn-out process, which involved engineers, flight controllers, safety managers, and even astronauts themselves, did NASA choose caution: Wilmore and Williams will remain on the station while Starliner returned alone.

NASA Administrator Bill Nelson framed the decision succinctly: “Spaceflight is hazardous, even when it seems like a go.” The decision conformed to venerable agency tradition—safety over schedule. Operations were modified by that decision. Starliner was certified for an uncrewed landing and descent, and the two astronauts were included in the station’s Expedition crew. Where an original short demonstration mission became an extended-duration visitation, Wilmore and Williams rapidly acclimatized, providing support for the science, maintenance, and distant-end testing of the Starliner systems until return arrangements were in abeyance.

On the ground, mission planners reorganized logistics. A subsequent Crew Dragon flight was delayed to make way for the eventual return of the astronauts. Starliner, after its desert landing, was flown back to the Kennedy Space Center for teardown and complete inspection. Scheduling of normal crewed flight certification was halted while Boeing battled through solutions and NASA considered the offer. Leadership at Boeing also shifted, with program jobs reorganized to rebuild momentum and confidence.

The event provoked media analysis and some opposition commentary on the web and in the press. Headlines describing the event as abandonment oversimplified: contingency planning never departed the mission, and the crew never were in a position where they were at imminent risk. In fact, the whole purpose of committing to two different commercial crew systems was so that there would be this kind of resiliency. Having a backup provider on standby to take over is not replication for replication’s sake — it is insurance against human lives and round-the-clock access to the station.

In the coming years, the future of Starliner is well-tended but promising. More uncrewed flights await it on its horizon before crews will fly again. It’s not the clean, straight path everybody wished, but where manned spaceflight is concerned, perfection matters less than adaptability. All breakdowns and fixes contribute to the collective expertise that keeps crews safer on the next flight.

In the end, this flight was more than a single test flight. It was an improvisational test of engineering discretion, program management, and crew health in the face of doubt. Far from failure, the episode illustrated how NASA and its contractors are forced to make difficult choices when the consequences are high. Starliner’s tale is far from over, but what it taught us about redundancy, conservativism, and disciplined problem-solving will shape the way America does crewed spaceflight for centuries to come.