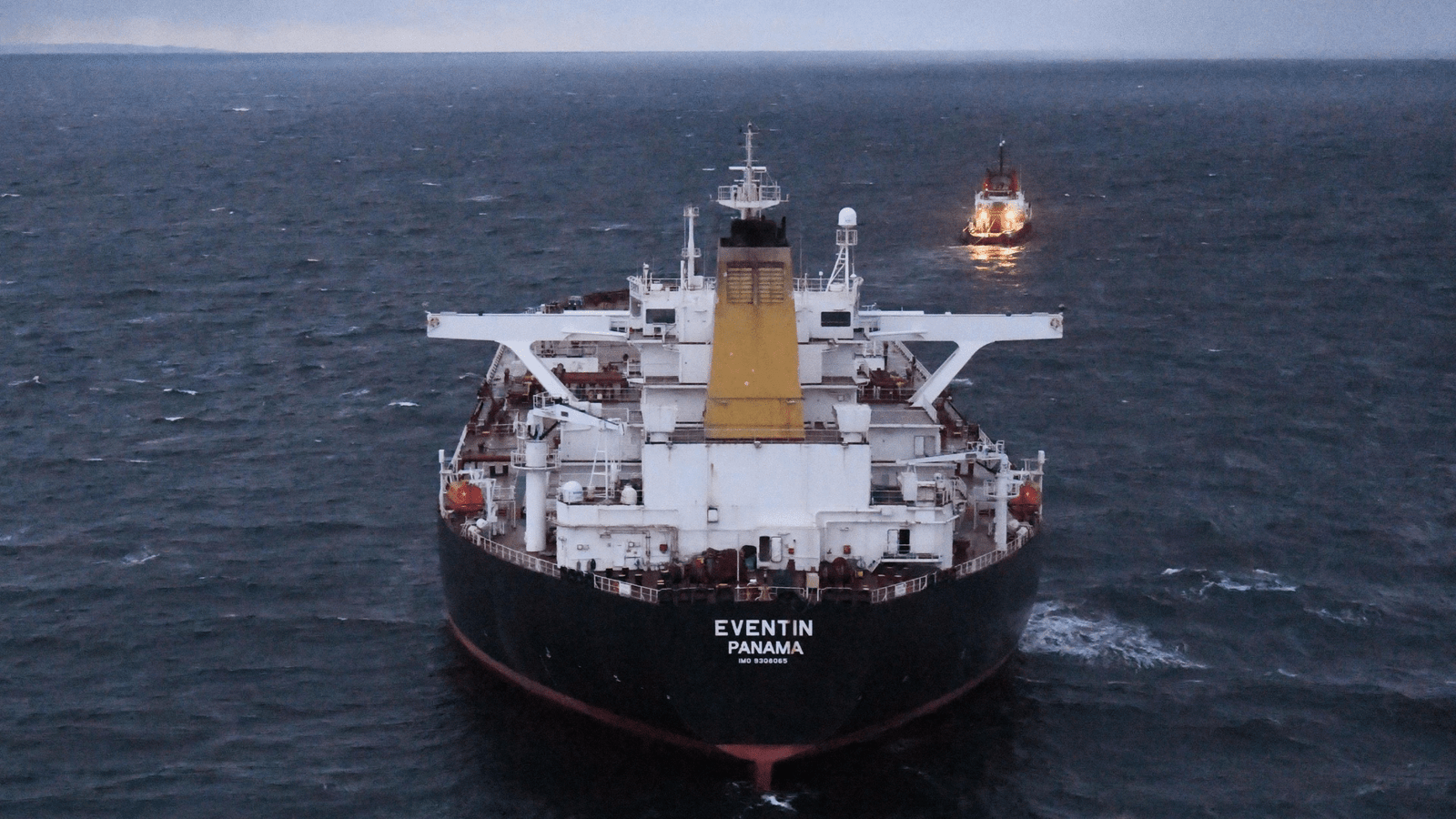

President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s threat was blunt: “According to our data, there are more than 500 such tankers. They have to be stopped in full, because it would have an impact on energy trade and European security. These tankers are also platforms which Russia employs to carry out drone attacks.” The figure he quoted serves to illustrate not only an economic issue but a very rapidly evolving security threat in European waters.

The Ukrainian intelligence puts Russia’s shadow fleet tankers at over 500, while French President Emmanuel Macron has used figures ranging from 600 to 1,000. The vessels operate under foreign flags—Benin, Aruba, Curaçao, and Sint Maarten among them—typically supported by fake registration papers. Ownership is concealed behind complex corporate ownership schemes, and vessels continually change names and flags in an effort to conceal their operations. The primary mandate began as sanctions evasion for the export of oil, but the function of the fleet has shifted towards hybrid war.

Security analysts describe how the vessels can be repurposed to carry and launch drones, making them deployable military bases. Peaceful hulls conceal reinforced decks for drone launch, enhanced communications arrays for distant control, and concealed storage for unmanned aerial systems. Ships like Boracay, also known as Pushpa, are thought to have been fitted with military-grade sensors to intercept encrypted communications and chart underwater infrastructure. These retrofits exploit the broad, stable deck space and high power redundancy of oil tankers, making them well-suited for extended drone operations from remote offshore locations.

As Basil Germond of Lancaster University has put it, “Some 97 percent of our online communication passes through undersea cables, which are becoming a target for hostile forces.” Shadow fleets are able to exploit their vessels to monitor these cables, pilfer information regarding weapons supply chains, and disrupt navigation systems. The divergent jurisdictions and broad oceans of the maritime space make attribution difficult. Erik Stijnman from the Clingendael Institute warns that “soldiers in disguise, civilians” can be sent from such ships, using cover for intelligence gathering without overt military intervention.

French soldiers boarded the Boracay off Saint-Nazaire on September 30, suspecting it of sanctions-busting and suspected drone launch activity linked to incursions into Danish airports. Its Chinese captain was accused of disobeying naval orders. The Benin-registered ship, which had undergone numerous changes in identity and once sailed without a proper flag, continued its journey towards the Suez Canal within a matter of days, pointing to how hard it is to completely stop such activities under prevailing maritime law.

France, Denmark, and Estonia are intensifying checks. Denmark has targeted Skagen Anchorage, one of the busiest Nordic shipping hubs, for green and security checks. Inspectors verify waste management equipment, ballast water monitoring, and scrubber discharge compliance, and verify flag validity and insurance certificates. On the Great Belt Bridge, sulfur emissions are monitored by “sniffer” sensors to enforce IMO SOx and NOx limitations, something that has been blended with airborne sniffer drones in past operations.

Monitoring the shadow fleet relies on satellite AIS data, SAR imagery, and thermal infrared sensors. Ships will also disable their transponders for SAR imagery gaps that are correlated with AIS gaps to detect “dark” ships. MarineTraffic platforms provide real-time position data, but analysts fill this in with classified military satellite imagery to monitor suspect vessels even in bad weather or at night. These tools are required to link ship movements to drone incursions or cable-mapping activities.

The EU’s 19th package of sanctions targets companies offering false flags and accelerates phasing out Russian LNG imports to January 1, 2027. It removes exemptions for the main Russian oil producers and boosts the number of sanctioned vessels by 118. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen explained, “Russia’s war economy is fueled by fossil fuel revenues. We want to cut these revenues.” But maritime law limitations—like the comparative impossibility of seizing ships beyond territorial waters—limit the reach of enforcement.

The use of hybrid maritime operations exploits vulnerabilities in NATO response protocols. As University of South Wales analyst Christian Kaunert pointed out, “If you don’t even have a policy on who is allowed to shoot down the drones, you are very obviously the weak point.” The alleged activity of the Boracay in drone incursions over Denmark shows how rapidly ostensibly civilian-shipping-lined ships can project military power into deep European skies. Russian submarine sightings off the coast of Gibraltar and repeated airspace violations in Poland, Estonia, and Romania reassert the magnitude of the threat.

The development of the shadow fleet from sanction-busting to direct hybrid warfare platforms is a synthesis of naval engineering, covert military development, and geostrategy. Lacking effective enforcement, augmented surveillance, and real-time attribution capabilities, these vessels will continue to operate in the maritime “grey zone,” both destabilizing economic security and stability across Europe.