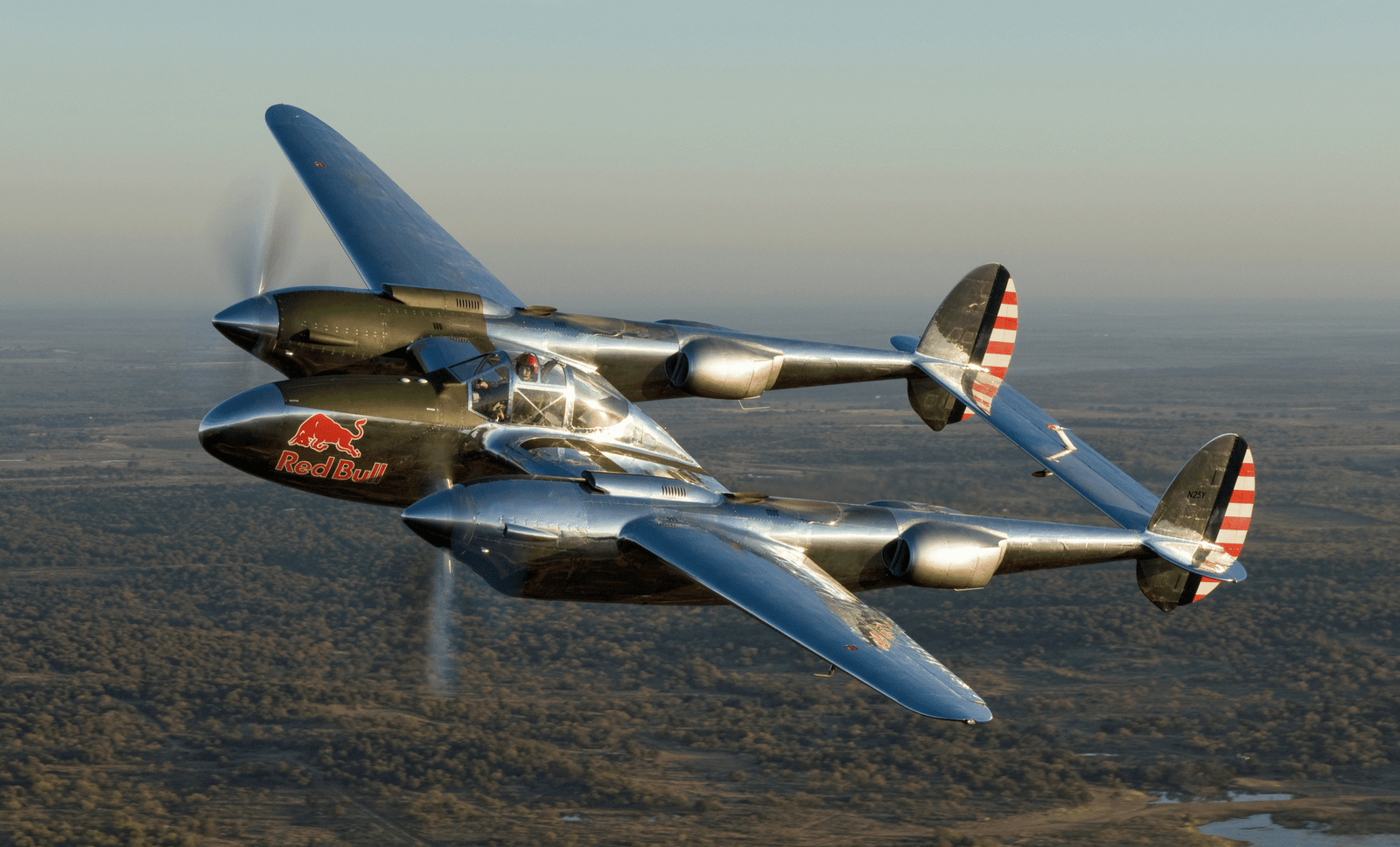

When the subject of the greatest fighter airplane ever made arises, the Lockheed P-38 Lightning finds its way onto the list. Conceived in the late 1930s by the brilliant designer Kelly Johnson and his staff at Lockheed, the P-38 was an ambitious departure into new aircraft design. With its double-tail boom, tricycle landing gear, and concentrated nose-mounted firepower, it looked like nothing on the horizon. But what made it actually unforgettable wasn’t necessarily its sheer appearance—it was its performance, adaptability, and the critical role it played in deciding whether or not World War II would be won.

Lockheed’s engineers undertook a tremendous task when they committed to building their first fighter. The U.S. Army Air Corps wanted an airplane that would outclimb, outrun, and outfight anything in the air. What resulted was a twin-engine marvel that could climb more than 3,000 feet a minute and reach speeds of more than 400 mph—blindingly fast for the time. Its armament—four .50-caliber machine guns and a 20mm—was fitted side by side in the nose, giving it unprecedented accuracy. Because it did not need gun convergence, the Lightning could attack targets at longer ranges with deadly precision. Its twin engines gave it range, stay time, and the attitude to perform long-range missions others could not sustain.

Brilliant as the P-38 was, it was not an easy airplane to fly. It took discipline and experience, and its pilots had to learn to operate its quirks. In the cold European skies, the lack of a front engine in the cockpit made for icy conditions, tending to leave pilots so chilled they had to be helped out of their planes upon landing. But for those who got to feel its beat, the Lightning was a pleasure to fly—powerful, fast, and capable of maneuvers other fighters could only dream about.

It was in the Pacific Theater that the P-38 forged its real reputation. With its magnificent span, it could escort bombers deep into enemy-occupied territory that no other Allied fighter could reach. Its speed and firepower were awe-inspiring, and its peculiar shape instantly recognizable to friend and foe. Japanese pilots called it the “fork-tailed devil,” a nickname which perfectly encapsulated both its fear and attraction. Allied pilots pinned that moniker to their sleeves with pride, sure the Lightning had earned it through sheer performance and unyielding supremacy.

There was one mission that took the P-38’s legend to mythic proportions—Operation Vengeance. American intelligence intercepted Japanese communications in April 1943 detailing the travel plans of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, mastermind of the Pearl Harbor attack. The Americans had an audacious response: a squadron of P-38s would take nearly 1,000 miles from Guadalcanal to intercept Yamamoto’s aircraft.

Against astronomically long odds, they succeeded. The Lightning pilots found the formation on time and brought down the admiral’s aircraft over Bougainville. It was one of the greatest exhibits of air power, precision, and planning of the war as a whole, and it showed the P-38’s enhanced capability at far-range missions.

Over 10,000 P-38s were produced, making over 130,000 sorties during the war’s numerous fronts. In the Pacific, it scored more air-to-air combat victories of any Allied fighter plane. In Europe, it served yet another essential purpose—reconnaissance. The speed, stability, and range of the Lightning were tailor-made for photographing enemy positions. P-38s took nearly 90 percent of all air photos used during the European campaign. All of America’s top aces, such as Major Richard Bong—the nation’s highest-scoring ace with 40 confirmed kills—established their reputations in this phenomenal aircraft.

While the war was winding down, Lockheed wasn’t content to ride its triumph. Engineers began designing the XP-49, a high-development version of the Lightning with a pressurized cabin and potential for 500-mph speed. However, jet technology was already rapidly evolving, and the XP-49 project was ultimately overtaken by a new generation of powerplants. Nevertheless, it produced valuable experience with aerodynamics and high-altitude flight that would be applied in subsequent aircraft design.

The P-38 also came in the midst of a change in the U.S. military’s perception of its aircraft. In the early years of the war, American planes were termed “pursuit planes,” with an emphasis on dogfighting as the highest priority. As the character of air warfare changed, however, the term “fighter” came into use, which better described a more inclusive, more adaptive function of offense, defense, and multi-mission capability. The P-38 was one of the first aircraft to capture this new philosophy—a plane for enduring whatever life threw at it.

Even years later, the Lightning’s legacy can be seen. When Lockheed Martin unveiled the F-35 Lightning II, the name was a respectful reference to the original. Similar to its namesake, the new Lightning is a symbol of innovation, adaptability, and air dominance. With generations between them, both are bound by the same spirit of innovative design and technological excellence that has always defined Lockheed’s aircraft.

At its core, the P-38 Lightning’s story is one of courage and engineering. It was an airplane that broke all the rules, coupling speed, range, and firepower into a package no airplane had before. From its characteristic twin-boom silhouette cruising the Pacific to its low-key, consistent service over Europe, the Lightning redefined what a fighter could accomplish. Even today, when sleek jets rule the air, the P-38 legacy endures—a reminder that outstanding innovation never perishes and that excellence, once achieved, echoes with every flight era.