When precision-guided bombs are the first thing that comes to mind, visions of laser-enabled attacks or GPS-enabled ordnance in the most recent wars tend to be cultivated—Desert Storm, Iraq, or the latest newsreel on television. Few are aware that the tale of “smart bombs” goes all the way back to World War II. Surprisingly, the first working guided bombs weren’t built in American research labs; they originated in Germany in the 1940s. The Henschel Hs 293 and Ruhrstahl Fritz X weren’t only advanced for their era—these weapons revolutionized naval warfare, establishing concepts that would influence military thinking for decades.

Years before satellites and electronic computers were on the scene, military engineers fantasized about bombs that could navigate on their own. Striking a moving vessel from the air was a task so challenging that it was almost impossible. Torpedoes and dive-bombing were matters of split-second timing, nerves of steel, and fortune, but even then, there was no assurance of success. It was a simple idea: drop a bomb and then guide it to the target.

It was much easier said than done. A number of nations experimented with pre-war radio-controlled designs during the interwar years, but none developed a system that could be used operationally. Germany, on the other hand, explored the concept more aggressively. Where the V-1 and V-2 missiles earned notoriety, they were terror weapons to be delivered against cities, not pinpoint targets. The Hs 293 and Fritz X, however, were designed to attack ships, and attack ships they did.

The Henschel Hs 293 was an outstanding specimen. Practically a miniature plane with a ten-foot wingspan and a thousand-pound warhead, it was not designed to destroy battleships but was deadly on troop carriers, freighters, and lightly armored vessels. With an added rocket motor, it could glide several miles after dropping. A German bomber, usually a Dornier Do 217, would ascend to heights of 3,000 to 5,000 feet and release the weapon.

The crew member then controlled the bomb with a joystick, using flares or tail lights to guide and aim it toward its target. The Hs 293 saw its first combat operations in August 1943 over the Bay of Biscay, targeting British ships. Early strikes did not detonate, but within a few da, ys it sank the HMS Egret, the first vessel in history destroyed by an air-delivered guided bomb.

A later attack on HMT Rohna killed more than a thousand American troops, the single deadliest engagement against U.S. forces at sea in the war. Although the specific Hs 293 occasionally struck land targets such as bridges, its real importance was at sea, where Allied commanders felt compelled to reconsider fleet defenses.

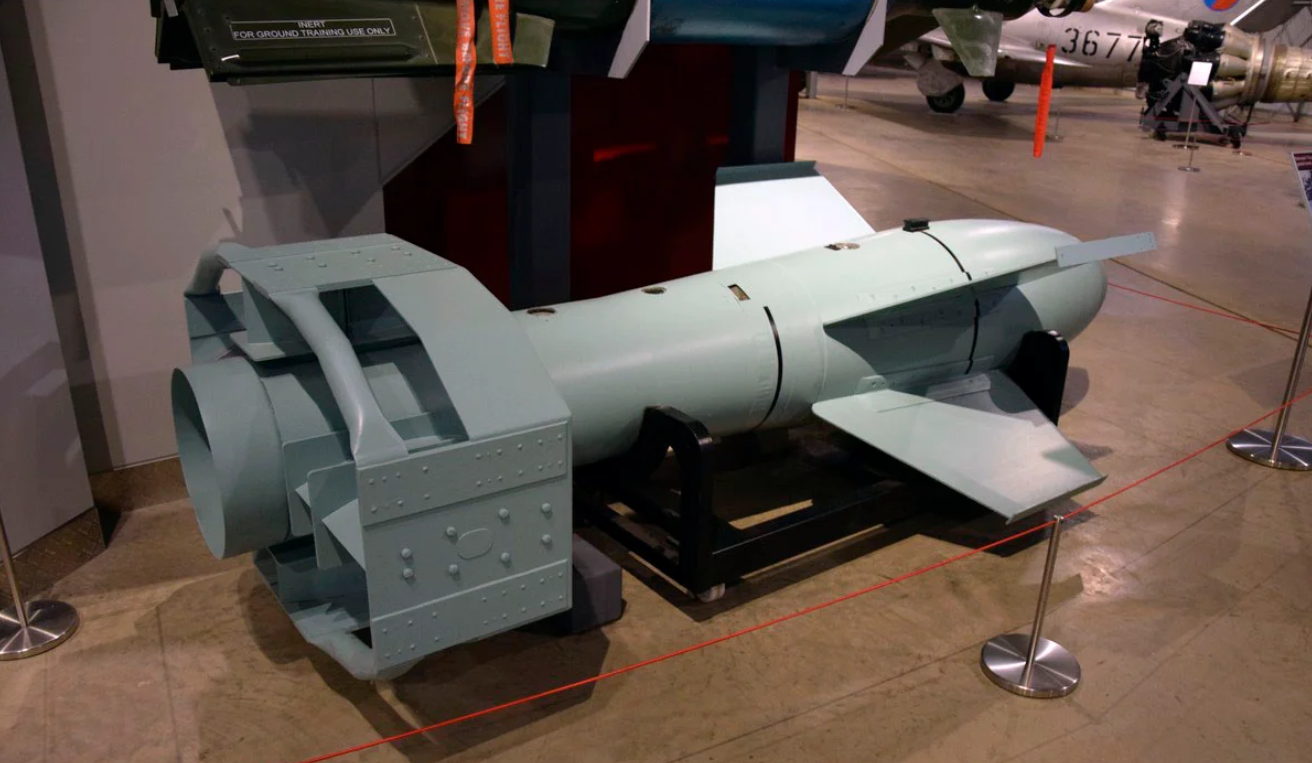

If the Hs 293 aimed at smaller vessels, the Fritz X targeted giants. Weighing almost 3,000 pounds with a 700-pound explosive warhead, it used gravity instead of a rocket motor, falling from as high as 20,000 feet to reach near-supersonic velocities at impact. Like the Hs 293, it was guided, and the Fritz X was also flown by radio control using flares as a pointer for its flight path. Its impact was catastrophic.

In August 1943, the Italian battleship Roma was hit while trying to surrender; one of the bombs incapacitated the ship, and another exploded a magazine, tore a turret off clean, and killed over 1,300 sailors in a matter of minutes. In the ensuing weeks, Fritz X bombs injured or sunk other Allied cruisers, the Savannah and Philadelphia, and even affected the British battleship Warspite. The system was not infallible, with only around one in five bombs striking directly, but the psychological and tactical pressure it wielded together was substantial.

The Allies soon discovered how these bombs were being directed and started jamming the radio signals, introducing the first electronic battles. This early game of cat-and-mouse between guidance systems and countermeasures predated the electronic warfare of today. Germany tried out wire-guided varieties, but the facts were evident: survival was a matter of height, speed, and shielding countermeasures.

Though neither the Hs 293 nor the Fritz X altered the final result of World War II, they left a lasting legacy. They demonstrated precision strikes as a possibility, brought battles to the electromagnetic spectrum, and paved the way for guided missiles and smart bombs of contemporary warfare.

These weapons revolutionized how militaries thought about striking targets with precision, laying the foundation for decades of strike technology and countermeasure innovation. The equipment has changed, but the underlying race between precision and defense, first seen over the Bay of Biscay and the Mediterranean, still drives military strategy today.