The A-12 Avenger II was meant to be the Navy’s leap into the future—an advanced, carrier-capable bomber that could fly through the most sophisticated defenses and reach deep into hostile territory. By the late 1980s, the dependable A-6 Intruder was aging, and with Cold War tensions on the rise, the Navy required an aircraft to perform in a radar-guided missile-filled world where air defense systems were more sophisticated than ever before.

This requirement created the Advanced Tactical Aircraft program with the mission to develop a next-generation stealthy attack aircraft for the carriers. Spurred on by the Air Force’s F-117 Nighthawk, the Navy desired its own cutting-edge solution. McDonnell Douglas and General Dynamics took the contract in 1988 and conceived the A-12 Avenger II—at least on paper.

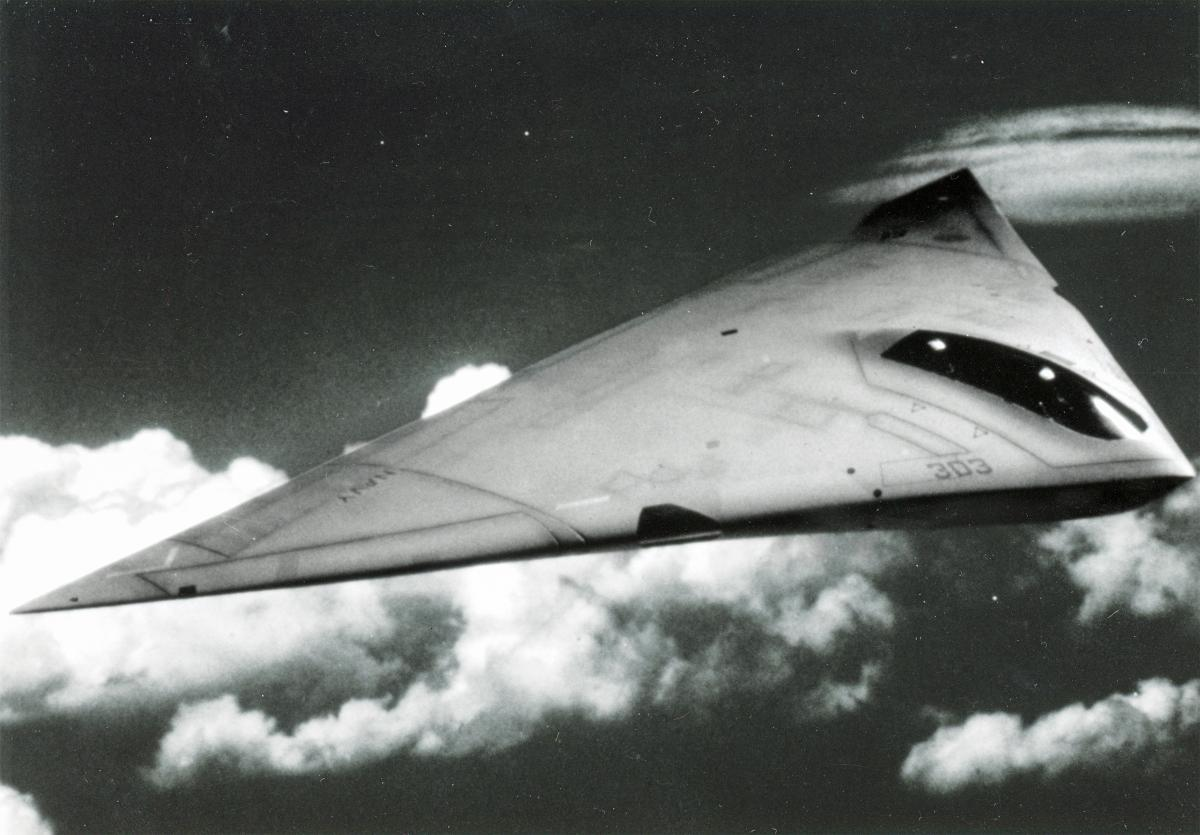

Its shape was radical and immediately identifiable: a triangular wing form, called the “Flying Dorito,” that held weapons internally to minimize radar detection.

Constructed of cutting-edge composite materials and treated with radar-absorbing paint, it was meant to seat two crewmen and feature cutting-edge avionics and electronic warfare technology. It was expected to have a range of more than 900 nautical miles, significantly longer than any existing carrier-based plane.

But translating this bold vision into a workable aircraft was much tougher than envisioned. Complying with stealth while enduring the extreme carrier stresses became a principal engineering problem. The weight of the plane continued to rise above early projections, threatening carrier safety. Adding to that, experimental materials and production methods imposed additional delays and technical nightmares.

Secrecy failed. As a classified “black” program, it was short of supervision. Congress and Pentagon officials were not in the loop about the growing issues, while contractors and Navy officials minimized the problems to prevent killing the project.

Costs skyrocketed. What began as a $4.8 billion development program nearly doubled to $11 billion, with each plane estimated to cost more than $165 million. By early 1991, the A-12 was 18 months behind schedule, billions over budget, and still grounded.

In January of that year, Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney canceled the program, marking the largest contract cancellation in Pentagon history. Only a full-scale mockup of the aircraft ever existed.

The repercussions were widespread. The courts were bogged down with legal battles between the government and contractors for over two decades before coming to a conclusion in 2014. In the meantime, the Navy was forced to substitute the F/A-18 Hornet, followed by the Super Hornet, to carry out tasks the A-12 was originally designed to do. The F-35C finally materialized on carriers, with stealth capability—but it was no real substitute for the bomber envisioned by the Navy.

Now, the A-12 Avenger II is a cautionary tale in the history of U.S. military aviation. It shows the risks of over-reaching with technology, underestimating difficult engineering, and keeping things too classified.

The “Flying Dorito” never flew, but its tale revolutionized the way the Pentagon handles ambitious weapons projects—focusing on oversight, realistic expectations, and prudent risk-taking before committing to the next generation of cutting-edge aircraft.