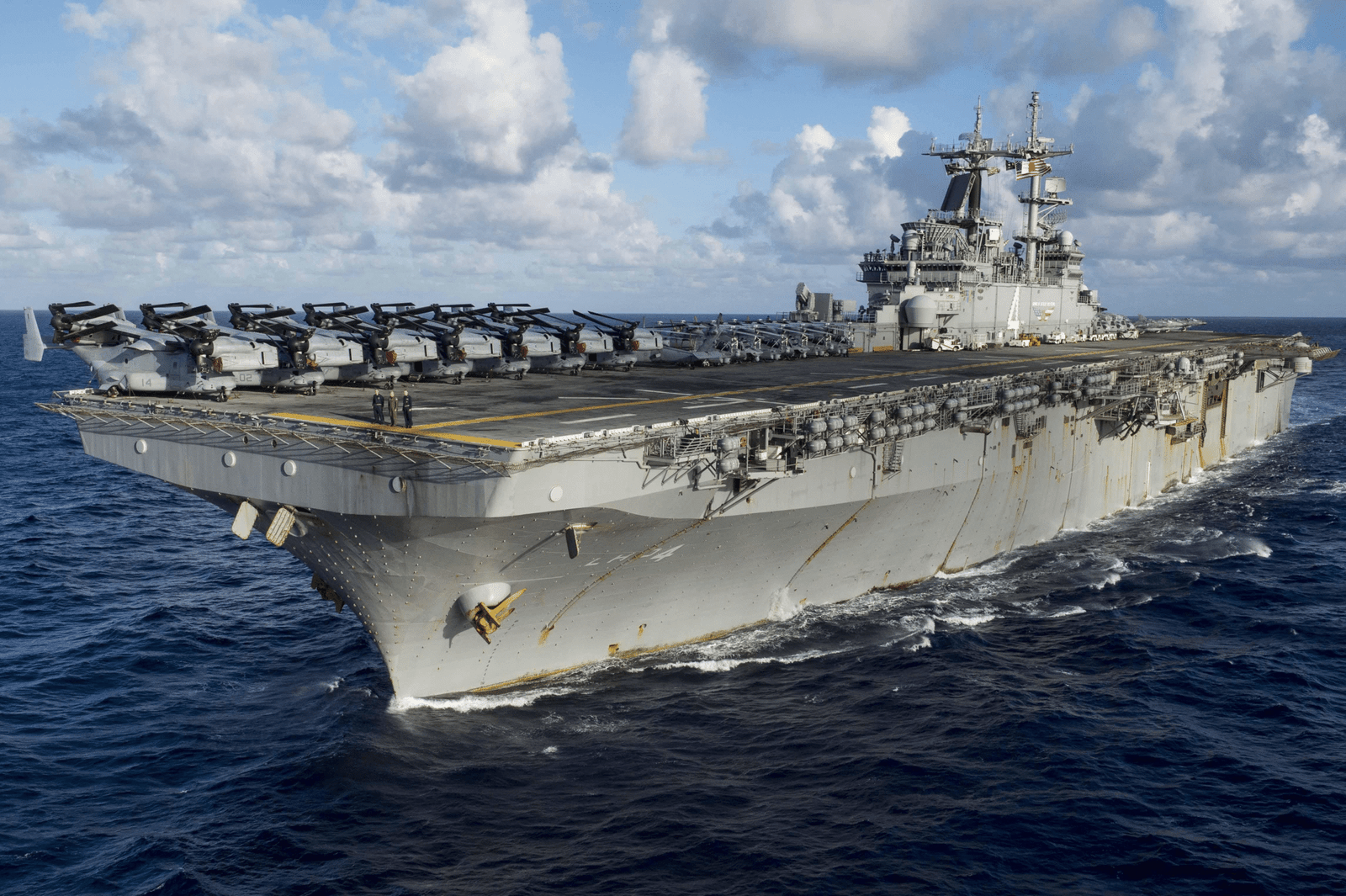

For decades, the U.S. Navy’s amphibious warships have been the workhorses of international crisis response—transporting Marines into the hottest combat zones on short notice. Today, that former-trusty fleet is creaking under the pressure of aging hulls, increasing maintenance backlogs, and a thinning workforce. The tale of the USS Boxer’s plagued deployment is merely a visible indicator of a larger, long-simmering readiness issue.

Mechanical failures have become the norm. The USS Boxer, a nearly 30-year-old Wasp-class amphibious assault ship, languished in overhaul for years only to endure repeated engineering problems, such as the failure of its starboard rudder that forced it to cancel a much-anticipated deployment. Navy Secretary Carlos Del Toro said repairs would be made pier-side in San Diego, potentially returning the ship to sea by summer. But the Boxer’s troubles aren’t unique—other Wasp-class ships like the USS Wasp and USS Iwo Jima have faced similar breakdowns, at times limping back to port with tugboat assistance.

This is more than bad luck. A Government Accountability Office review found that half of the Navy’s 32 amphibious ships fall short of the service’s condition standards. Others have spent years at a time out of commission, and between 2010 and 2021, maintenance downtime totaled almost three decades of lost deployment and training time for Marines. Adding to the problem, steam propulsion systems employed on these vessels are nearing the end of their support period and losing their masters in the skills required to keep them running.

Gaps in leadership and training have compounded the problem. Investigations into the Boxer’s engineering department disclosed a substandard command climate, poor compliance with procedures, and an inadequate number of experienced supervisors. Rear Adm. Randall Peck said that top engineering leaders did not foster a safe and professional work environment—shortcomings that had direct impacts on the ship’s deployment readiness and the strike group’s mission.

Piling on the pressure, the Navy is short over 18,000 sailors at sea, with some Wasp-class ships going along at about 80% of what they need to operate effectively. That manpower shortfall, combined with scarce hands-on training, makes it nearly impossible to maintain complicated ships fully online, much less from distant home ports.

The ripple effects are profound. The Marine Corps, which relies on these ships for its speedy Marine Expeditionary Units (MEUs), has watched all opportunities for actual-world missions go by. There was no MEU on the ground when major crises occurred in recent years, from civil strife evacuations to relief efforts following natural disasters.

Without a persistent presence of these “global 911” units, U.S. deterrence and credibility suffer. As one defense commentator characterized it, recurring unavailability starts to create a scenario of lack of preparedness—something foes are bound to observe.

The Navy is attempting to reverse the trend. New shipyard infrastructure, such as increased dry dock capacity in San Diego, seeks to alleviate maintenance backlogs. There’s also an emphasis on new solutions, such as 3D printing, to rapidly manufacture hard-to-obtain parts, saving lead times and costs. As Lt. Cmdr. Jake Lunday said, having the capability to print parts on demand accelerates learning and enhances efficiency. Nevertheless, such improvements can’t eliminate years of postponed modernization.

The controversy surrounding new ship acquisition has further hampered progress. For decades, the Navy was reluctant to commit to multi-ship contracts for new amphibious ships, citing uncertainty regarding future force requirements.

Congress has intervened, mandating minimum fleet size levels and preventing the retirement of older ships without replacements. But the average age of the fleet continues to rise, and modernization of steam-powered ships becomes ever more costly annually.

The amphibious force of the Navy is at a critical juncture today. Without continued investment in newbuildings, improved maintenance facilities, and a more robust, better-trained crew base, the danger is obvious: the next time a crisis requires an instant reaction, the ships may not be available—not due to a deficiency of will, but because they literally cannot get out of the pier.