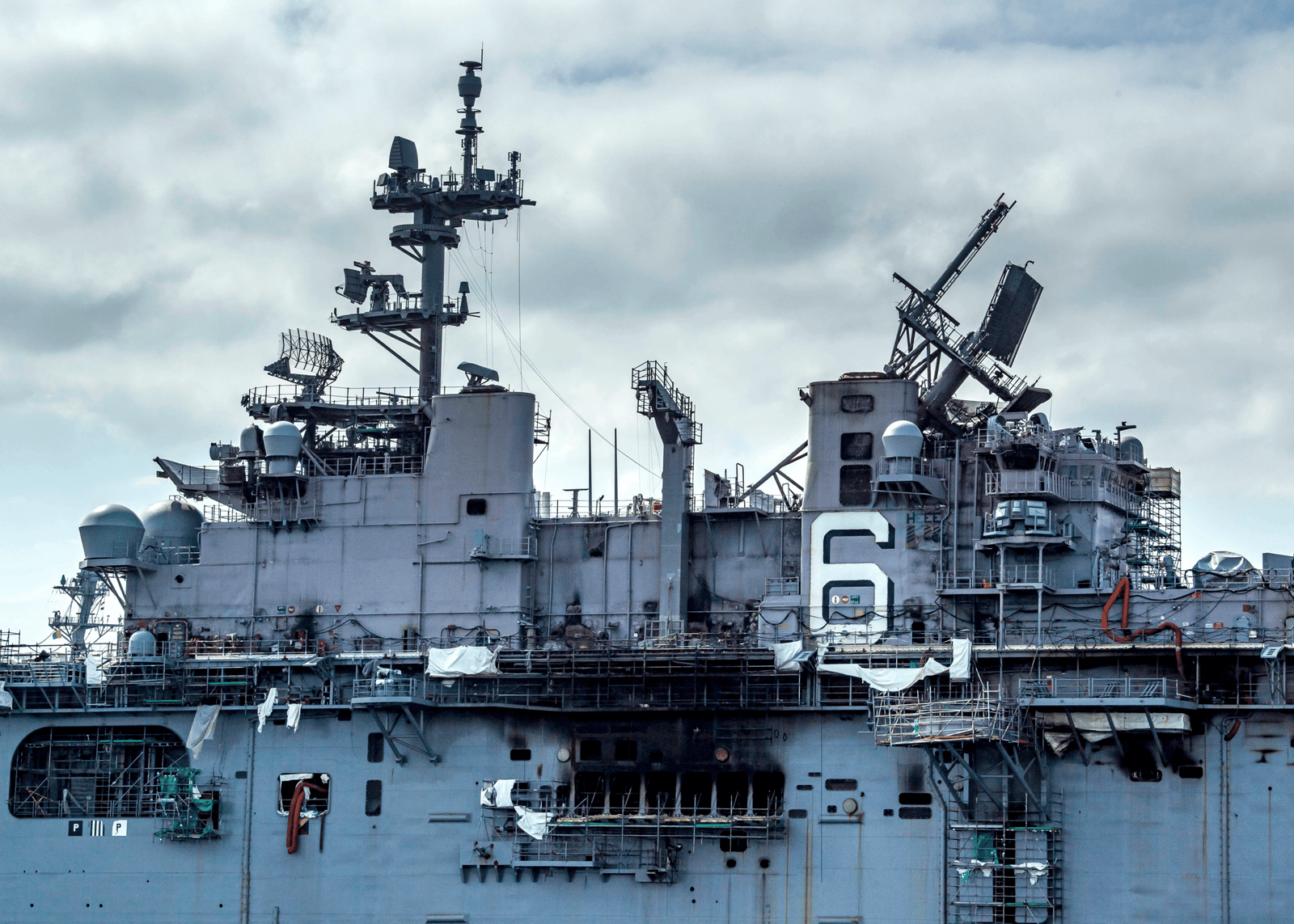

When the USS Bonhomme Richard burned at Naval Base San Diego in July 2020, the Navy endured one of its worst peacetime tragedies in modern times. Fire burned for almost five days, ripping through decks and compartments before the vessel was beyond recovery. More than two decades of service would end with the noble amphibious assault ship being decommissioned and scrapped—a fate decided not by the enemy, but by malfunction at every level.

The loss was about more than steel, hardware, and dollars. It revealed disturbing fissures in safety culture, maintenance rigor, and leadership—provoking uncomfortable questions about the Navy’s capacity to protect its own fleet.

The fire started on July 12 in the morning inside the Lower V space. The ship was then undergoing a $249 million upgrade that would have enabled it to handle F-35s. Yet in that compromised condition, the ship was a tinderbox. Almost 90 percent of its fire suppression outlets were inoperative, and workplaces were littered with combustible materials. The situation called for haste, but the initial reaction was lacking.

With radios out, crew members communicated by personal cell phones. The officer on deck was slow to call a general alarm, hoping the smoke had an innocent explanation. The valuable first few minutes—when any shipboard fire can still be extinguished—got away. When finally teams attempted to battle the fire, they found hoses inoperable or missing, issues that regular inspections should have revealed long before.

As the flames spread, civilian base and San Diego city firefighters came on board. Without common communication systems or a common plan, however, coordination fell apart. Crews battled the same fire alongside one another but not as a team.

The Navy’s later investigation branded it a “command-and-control vacuum.” Direction didn’t really pick up until Rear Adm. Philip Sobeck of Expeditionary Strike Group 3 showed up, but by then, the fire was too late to be stopped.

The government report was bleak. Drills had been irregular, and most sailors were not adequately prepared to battle fires within a shipyard environment or to merge with civilian crew members. High-priority safety systems were inoperative or ignored. Regulatory agencies did not enforce long-standing rules, and lessons learned from the 2012 fire on the USS Miami were disregarded. Briefly put, this was not the breakdown of one leader or one choice, but of a whole system in which the corners were cut until catastrophe hit.

The investigators called for disciplinary measures against 36 Navy leaders, from ship officers to regional command personnel. To what extent those recommendations were translated into permanent accountability has never been fully revealed.

The cost to the finances was enormous. It would have cost over $3 billion and seven years of work to repair the ship. Even repurposing it as another vessel, such as a hospital ship, would have cost over $1 billion. The Bonhomme Richard ultimately ended up being sold for scrap for under $4 million and pulled away to be dismantled.

The loss left the Navy’s amphibious assault fleet at nine ships and postponed the Marine Corps’ deployment of F-35Bs from the sea. In addition to quantities, the fire highlighted an uglier fact: the Navy does not have the industrial depth necessary to rapidly replace or recover a significant warship lost away from combat. As retired Capt. Jerry Hendrix noted, the true threat is not just that ships are exposed to attack, but that America’s diminished ability to rebuild when they’re destroyed.

The loss of the Bonhomme Richard is a sobering reminder. When safety culture breaks down, maintenance shortfalls build up, and leadership fails, even one of the Navy’s largest vessels can be lost without the firing of a single enemy round. The task now is to see that those hard-won lessons are turned into real change—before history repeats itself on someone else’s deck, on another crew.