Plane designations are more than letters and numbers painted on the side of an airplane—history, necessity, and occasionally even superstition in the military are inscribed within them. From a patchwork of service-specific codes, the U.S. military’s system of designating its planes has transformed into a more standardized system. Even today, though, new technology and shifting needs continue to redefine airplane designations.

Both the Navy and the Air Force employed their own terminology during the early years, creating a confusing array of codes and letters. In 1962, the Tri-Service aircraft identification system was established to impose order.

The goal was simple: aircraft across the Air Force, Navy, Marines, and Coast Guard needed to use the same “lingo.” Terms like “A” for attack, “B” for bomber, and “F” for fighter became common, although multiversion aircraft like the F-35 have swept away these classifications.

The system has never been in short supply of quirks. Numbers disappeared for reasons that seem more myth than logic. F-13, for example, was left out due to triskaidekaphobia, the fear of 13. F-19 was reduced to a ghost in the program, supposedly being withheld for a secret project or left out to avoid confusion with Soviet jet numbering.

Meanwhile, the YF-17, the runner-up to the F-16 in the Air Force competition, became life as the Navy’s F/A-18 Hornet, a mainstay of carrier air power.

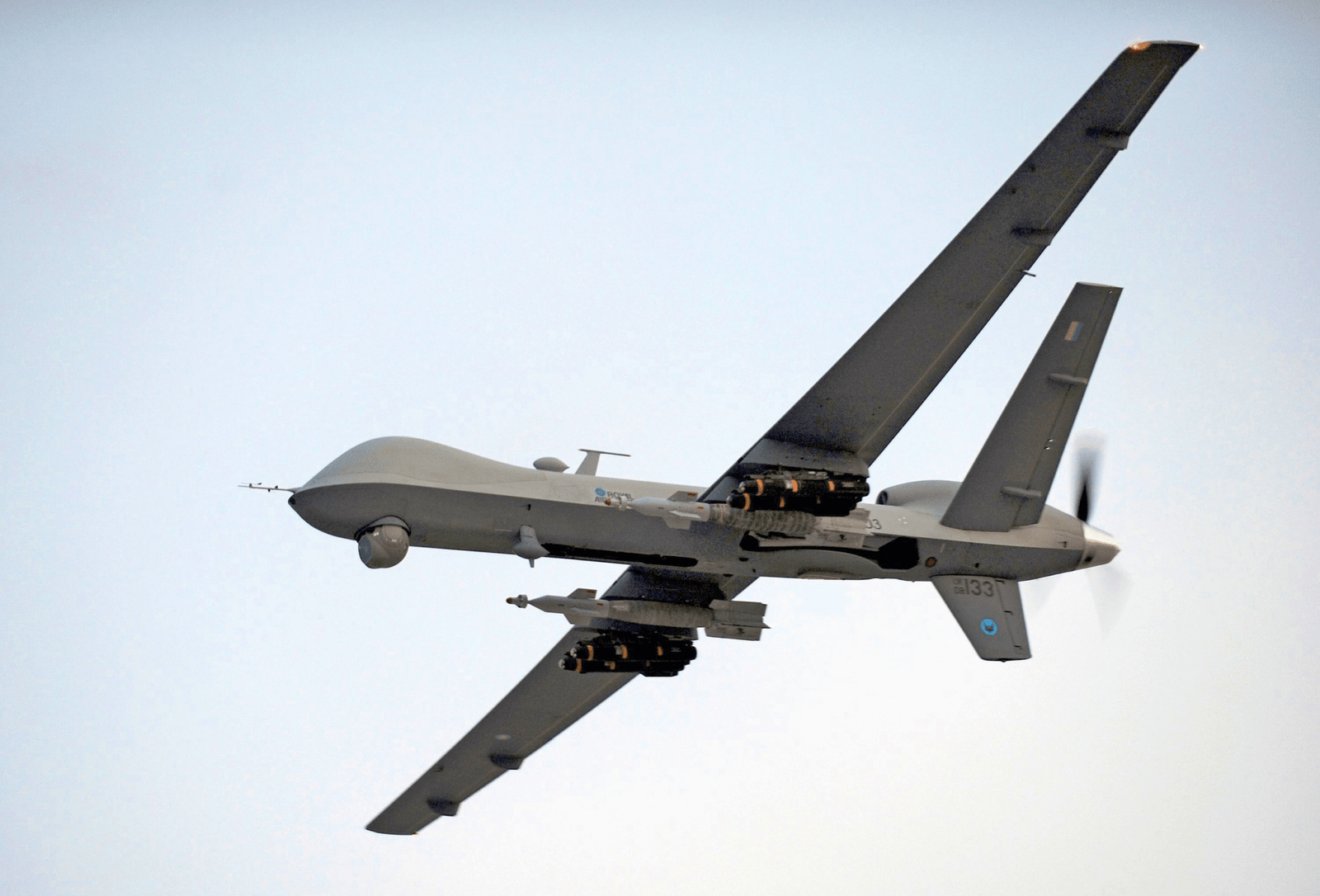

With evolving aviation technology, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) also came into the limelight. Drones used for target or spying purposes had the “Q” prefix in the beginning. But when such planes evolved from rudimentary stages to full-fledged combat aircraft, the naming trend also needed an upgrade.

In 2025, the Air Force officially assigned the first “fighter drone” designations to collaborative combat aircraft (CCAs). General Atomics and Anduril revealed YFQ-42A and YFQ-44A, a new milestone in modern military aviation.

These new designations provoked controversy all at once. Some opined that the Air Force might simply have employed empty designations between F-24 and F-34, with a “Q” to indicate unmanned status. Others pointed out that historically, “Q” indicated a target drone, not a combat-designed UAV. The difference matters: these CCAs were designed for combat, to augment or even supplant manned fighters in a variety of roles.

The missing YFQ-43A also attracted attention. A source explained that in four-ship sections, flight or element leaders occupy the -1 and -3 positions, and CCAs serve as wingmen—thus no number. It may sound mysterious, but it’s only a military rationale.

What all this signifies is significant: unmanned aircraft are no longer just observation or training platforms—they are recognized as legitimate threats. By giving them fighter designations, the Air Force acknowledges their position in air warfare history. The system of designations, with all its flaws and gaps, is being revised with the changing technology that it represents.

The difference between manned and unmanned aircraft, between fighter and attack missions, is less clear. As the Air Force and its contractor allies continue to push the boundaries of air warfare, so too will these naming conventions evolve—occasionally sensibly, occasionally strangely, but always reflecting the changing reality of flying today.